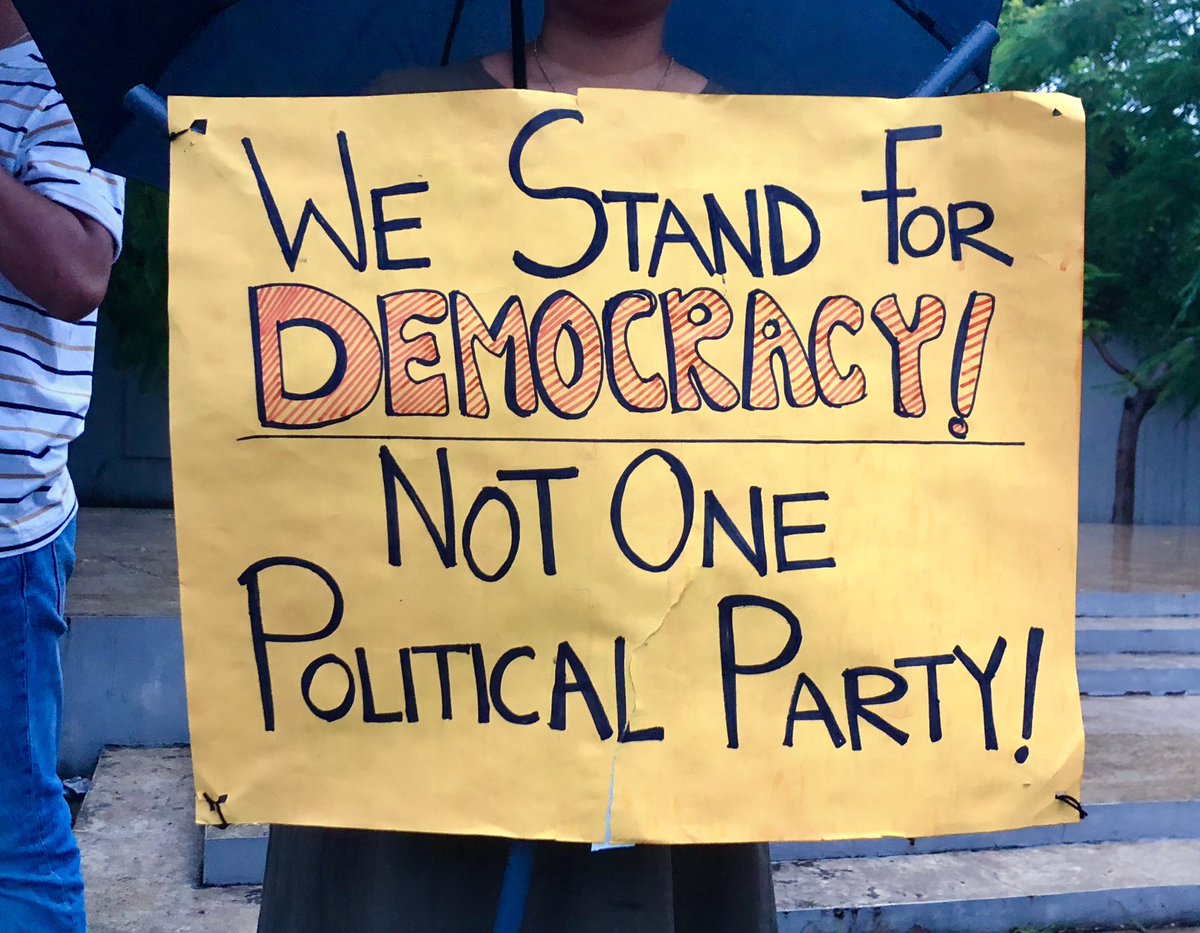

Image: A protester during the Oct 2018 constitutional coup.

In democracies, elections usually are significant political turning points. In democratic theory, an election marks two key opportunities to the people as well as the rulers. For the people, it marks the periodic occasion to elect their rulers and grant them authority to rule over them for a specific period of time, usually, five years.

For the rulers, incumbent or aspiring, an election provides legitimacy to rule. Legitimacy entails both legality and popular support. Legitimacy secured at a free and fair election is an essential precondition for democratic government. The absence of legitimacy secured through elections usually erodes the authority of the rulers and eventually the State.

Sri Lanka’s citizens are awaiting two crucial elections in the year 2019, Presidential and Parliamentary. Of the two, the presidential election is destined to be most crucial for the democratic future of Sri Lanka. It has the potential to determine the country’s future political directions, nature of the Sri Lankan State as well as the state-society relations.

Impending clash

This political significance to the forthcoming presidential election emanates from a single factor. It is the slow building up of a head-on clash between two political projects, parliamentary democracy and autocratic authoritarianism.

Versions of both, democracy and authoritarianism have been present in Sri Lankan politics in weak forms for decades.

Similarly, political power has been competitively shared by weak democratic and ‘soft’ authoritarian forces through electoral competition, coalition formation, and alliances with various social and ideological blocks. Moreover, governments themselves –whether led by the SLFP or the UNP– have been varied mixtures of weak democracy and soft-authoritarianism.

The story of Sri Lankan democracy’s survival, resilience, and continuity is also interspersed with aborted attempts to enthrone populist and hard authoritarian regimes under the so-called strong rulers. The Rajapaksa administration after 2009 was the last such regime. The constitutional coup of October 26, 2019 was the most recent attempt by a hard authoritarian alliance first to capture the Constitution and then the State.

Sri Lanka’s uneasy and tension-ridden co-existence between weak democracy and soft authoritarianism seems to be now facing a moment of transition. It is not because the democracy project has acquired new strength and vitality, but because the authoritarian project has entered a phase of a harder version of it under the leadership of a former military office who has also served as the country’s Defence Secretary during the last phase of the civil war.

The hard authoritarian project is being backed by a new coalition of political, social and economic forces that see democracy, freedom and human rights as outdated and irrelevant political liabilities that need to be abandoned, and abandoned forthwith. This coalition is preparing for the Presidential election to seek a popular mandate for their immediate goal of capturing political power through democratic means.

The media speculation that Sri Lanka People’s Party (SLPP) is likely to field Gotabaya Rajapaksa as its Presidential candidate has provided a new impetus to the clash between democracy and authoritarianism in Sri Lanka’s current politics. If the SLPP, currently led by two Rajapaksa brothers — Mahinda and Basil — endorses Gotabaya as its candidate, the Presidential election campaign will certainly be one marked by a clear polarization among political forces.

Gotabaya’s ideology

There are two significant features of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s new political ideology, which he propagates with a great deal of conviction through spoken and written word.

The first is the claim that the country needs a strong ruler and an equally strong government to ensure political and economic stability and development in place of weak and vacillating ‘liberal’ leaders and governments. This indeed has been a subterfuge resorted to by most autocratic rulers and dictators to capture state power.

The second is the assertion that Sri Lanka does not need democracy, individual freedom, or human rights. Gotabaya Rajapaksa preaches that liberalism which sustains these normative fundamentals have become anachronistic to today’s world and unsuitable to Sri Lankan people.

The world has seen this twin argument advanced in many Latin American, African and Asian countries since the late 1950s. It was an argument that had an appeal at that time among sections of the military, bureaucratic and business elites of many developing countries. In Asia, several countries such as Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Burma, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea and later Bangladesh followed this path. More recently, business and political elites in the Maldives returned to this option after a brief democratic interlude. However, with disastrous consequences of these developmental hard authoritarian experiments, and their excessive political and social costs, its lure disappeared. Except in Singapore, all authoritarian regimes have been replaced by democratic regimes. Only in Thailand, the military has returned to power, after popular protests against a corrupt democratic regime.

Weak Democracies still better

Thus, compared with hard authoritarian ‘strong’ governments and ‘strong’ rulers, weak democratic regimes are more the rule than the exception in Asia and elsewhere. Weak democratic regimes are weak due to a variety of reasons. The ideological commitment to thin versions of political liberalism, enmeshing of electoral politics with corruption, promotion of ethno-nationalist sectarian politics, weak commitment to human rights and freedoms, and the neglect of social and other inequalities are key among such reasons.

Why do people seem to prefer weak democracies to strong autocracies? The answer lies in the inherent and unique quality of democracy. Democracy is not only a form of government; rather it is also a form of human civilization, perhaps the only form that values and celebrates human freedom, equality, diversity, and dignity. As a political doctrine, it is the only one that promises, and often succeeds, though not always perfectly, in that promise that all citizens are equal and entitled to equality, without any form of discrimination based on gender, class, ethnicity, religious belief or disability. In contexts where these rights and equalities are denied, governments committed to norms, values and promises of democracy allow citizens to dissent, protest, demand, and mobilize themselves to secure them, without facing State violence.

As a form of government, it is the only one that offers a paradigm of empowered and equal citizenship in which the citizens as voters have an inalienable right to elect their rulers, authorizes them to rule, freely criticize the rulers when they go wrong, replace them when they continue to go wrong, and thereafter continue to live in freedom without facing the risk of being arbitrarily arrested, tortured or disappeared in vans, white or black.

That is why imperfect democracies are still worth protecting against their illiberal, undemocratic alternatives.

Popular imagination

The voters and the democratic forces of the Maldives, our small neighbour, are the latest to show the world that democracy is a political goal worth fighting for, without letting a powerful coalition of autocratic business, political and bureaucratic elites to capture their political imagination.

In the run up to the coming Presidential election, the battle lines are already drawn. The encounter is most likely to be in the form of a clash between democracy and autocracy to capture the political imagination of the masses. It has already taken a clear ideological turn, with Gotabaya Rajapaksa spelling out his authoritarian project as an anti-liberal democratic crusade.

This is why Sri Lanka’s democratic forces, organized in and outside political parties, cannot take the next Presidential election for granted. It is a crucial political moment that will decide the democratic political fate of its citizens. Despite their individual party or organizational agendas, they would all have to work together to prevent the political imagination of the masses to be captured by the new coalition of hard-authoritarian, autocratic forces. Thus, the election campaign will be a huge ideological battle as well.

Therefore, Sri Lanka’s weak democrats too have to become hard democrats to face the onslaught by hard authoritarians.

Only a broad coalition of all democrats, hard or weak, can prevent the hard autocrats from capturing the popular political imagination, and then the State, sometime during this year.

Conversation

The exact nature and dynamics of such a broad democratic coalition is not yet clear. Only a sustained conversation will help us to have any clarity about them. In other words, it has to begin as a coalition of ideas among democrats, given the fragmented nature of Sri Lanka’s political society.

At present, one can develop only some preliminary suggestions merely to generate thinking and reflection.

For example, this broad coalition may ideally be a lose alliance that promotes a conversation with the democratic elements within all political parties, blocs and movements– the UNP and UNF, the SLFP and the UPFA, SLPP, JVP, TNA and other Tami parties, SLMC and other Muslim parties, the Left parties and groups, civil society movements and groups, and individual citizens.

The main task ahead for these democratic elements in conversation may well be to launch, individually or in blocs, an ideological and programmatic struggle for protecting democracy against emerging hard authoritarianism.

If they are parties, they will advance democratic reform agendas that are designed to re-strengthen the legitimacy of democracy and in turn sustain, not undermine, the democracy discourse in the country. This they can do while pursuing their own agendas at the Presidential and Parliamentary elections. If they are civil society groups and individual activists, they can work with all or any organization involved in the struggle to prevent the surge of hard authoritarianism.

Reinventing and re-launching the democracy conservation across party and group loyalties is the need of the hour. Once the conversation gets stabilized and sustained, its political outcomes may also appear in the horizon, sooner than later.

(Sunday Observer 01.04.19)