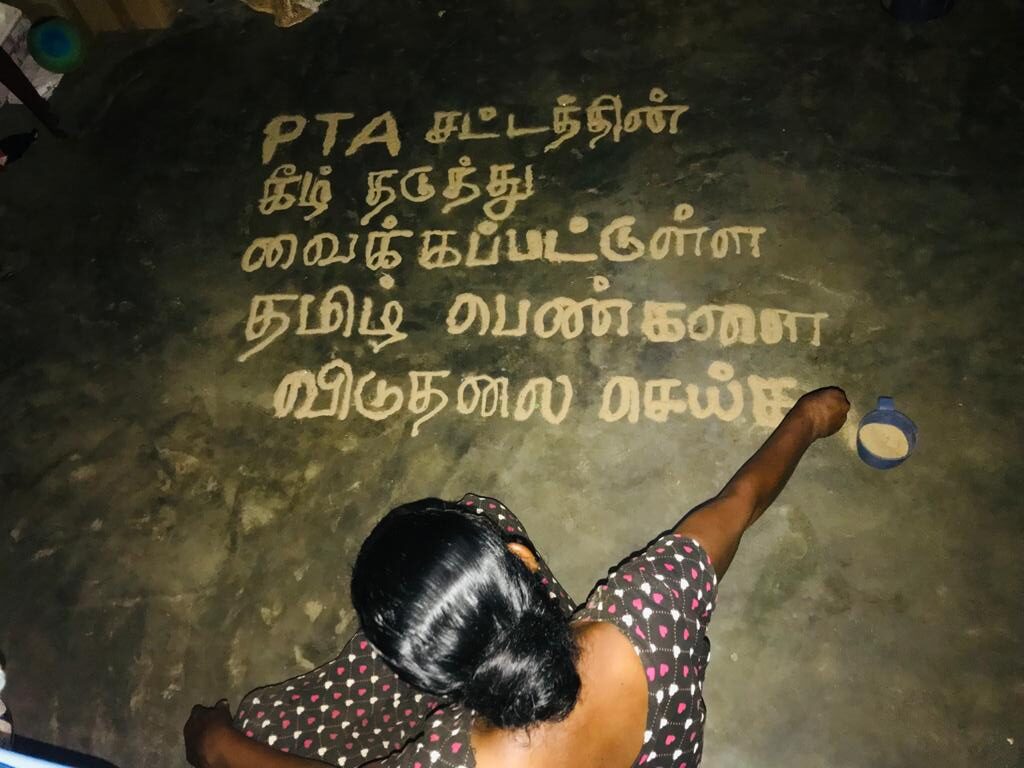

Image: No to PTA & calling for release of PTA prisoners.

Civil Society Statement on Government Proposals to Reform the Prevention of Terrorism Act

In June 2021 the government of Sri Lanka announced it would ‘reform’ the Prevention of

Terrorism Act (PTA) and appointed a Ministerial Sub-Committee for that purpose. It was

reported in the media that Kamal Gunaratne, the Secretary, Ministry of Defence and the

head of the Technical Committee that functions under the Ministerial Sub-ommittee, submitted the Technical Committee’s recommendations to the Ministerial Sub-Committee in November 2021.

Historically, for decades, the PTA has been weaponized against the Tamil community, and

following the Easter attacks against the Muslim community as well. This has resulted in

the victimization of members of these communities. It was also used against the Sinhalese

during the JVP insurrection and now against dissenters. We reiterate that any process which seeks to tackle issues related to the PTA must address this factor to ensure those

adversely affected by the law will receive justice, including reparations.

While the government has not shared its plans for the supposed “reform” of the PTA with

the public, we note the Sri Lanka Consensus Collective’s (SLCC) statement of 29 November 2021 sets out proposals for reform the government shared with the said group. In the absence of official communication by the government, we consider the elements contained in the SLCC statement as the changes being deliberated by the government. We note that nearly all so-called changes proposed already exist in law and do not address any of the shortcomings in the PTA that enable grave human rights violations.

We call for repeal of the PTA and in the interim an immediate moratorium on the use of

the law. This is in line with the requests of persons and communities adversely affected

by the law. We reiterate that any law that purports to deal with terrorism must adhere to

international human rights standards. In this regard, we set out below the provisions of

the law that result in egregious human rights violations and the minimum standards that

have to be followed to ensure the protection of fundamental rights.

The critical factor to take note is that the PTA is a human rights deficient law that does

not adhere to basic human rights standards enshrined in international conventions, such

as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which the government

of Sri Lanka has ratified and hence has an obligation to respect and protect. Nor does it

adhere to many provisions in the Constitution of Sri Lanka. In this context the following

are key provisions in the PTA that result in grave human rights violations:

• The PTA does not contain a definition of terrorism. Instead, the offences stipulated

are those found in other laws, such as the Penal Code, to which the PTA makes reference. Hence, the decision as to whether the PTA would apply in a certain instance is a subjective decision that can be shaped by personal prejudice and bias, rather than objective standards. In this regard, the PTA does not adhere to the definition set out by the UN Special Rapporteur on Countering Terrorism while Protecting Human Rights. For instance, post- Easter attacks even persons with books in Arabic and decorative swords were arrested. Similarly, those memorializing the lives lost at the end of the war have been arrested.

• The lack of basic due process safeguards in the PTA enables arbitrary arrest and detention, which continue to date. This is exacerbated by the lengthy periods of

administrative detention. For example, for decades we have witnessed persons who had any connection to a person accused of an offence in the normal course of their employment or personal life being arrested, without investigations being conducted, and detained for months.

o We reiterate that arrests should be made based only on evidence following investigation or reasonable suspicion.

o The detention period should be that stipulated in the Code of Criminal Procedure and any extension of detention should be made by a judge, who should be satisfied of the reasons for continued detention and exercise discretion as to whether or not to extend detention.

• There is documented evidence, including Supreme Court decisions and the Human

Rights Commission’s (HRCSL) reports, which illustrate that the admissibility of confessions made to an Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP) or above as evidence, has resulted in persons being tortured to extract confessions. This has normalized and entrenched the use of torture. Even if the confession is ruled inadmissible during trial, the existence of the provision creates room for persons to be subject to torture. This not only violates basic due process and fair trial rights of a person accused of an offence, but also calls into question the competence of the criminal justice system that has to rely on confessions to prosecute persons.

Such a provision, which is a deviation from the norm, has no place in law. Instead,

current provisions in the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Evidence Ordinance

should be followed with regard to the admissibility of confessions.

• Section 7(3) allows a person to be taken out of judicial custody to any other place for investigation. Section 15A empowers the Secretary, Ministry of Defence, to determine a person’s place of detention even after the person is remanded. This removes a person from the protection of judicial custody and empowers the Secretary to override a judicial order. The incident in September 2021 of the Minister of Prison Reforms and Prisoners Rehabilitation Affairs entering Anuradhapura prison and reportedly threatening persons detained under the PTA with a weapon and verbally abusing them illustrates the insecurity faced by such persons even when in judicial custody. Removing them from judicial custody

would only exacerbate their vulnerability. As the Human Rights Commission’s national study of prisons documented, persons remanded under the PTA were subjected to severe torture when taken out of judicial custody or held in other places upon the instructions of the Secretary, Ministry of Defence.

• Persons detained under the PTA spend a prolonged period of time in pretrial detention because the Act requires such persons to remain in remand custody until the conclusion of the trial, unless the Attorney General consents to the release on bail. For all arrests, provisions of the Bail Act should apply, and bail should be denied only if any of the exceptional circumstances set out in the Bail Act are met.

• The PTA allows the Minister of Defence to issue Restriction Orders for up to 18 months. Restriction Orders can be used to prevent people from engaging in political activities, speaking at events, or advising an organisation. Such orders allow civic rights to be curtailed arbitrarily by the Minister with no due process, transparency or accountability.

Protections

The SLCC statement mentions the government stated that for the very first time a detained person would be able to challenge administrative detention in the Supreme Court. We point out that the right to challenge arbitrary detention, including under the PTA, is enshrined in the Constitution of Sri Lanka and is not a new right that any proposed reform could bestow. The challenge many detained persons face in accessing this existing right is the administrative restrictions on access to lawyers and lack of financial resources to retain competent counsel.

Similarly, the HRCSL Act already mandates the Commission to monitor the welfare of persons deprived of liberty and empowers it to access any place of detention unannounced. However, following the 20th Amendment to the Constitution in 2020, the HRCSL is no longer a legally independent body as appointment of the officers of the Commission is at the discretion of the President. This adversely impacts the activities of the Commission as well as public trust in the institution.

The Advisory Board established by Section 13 of the PTA, as we have pointed out in the past, is an inadequate protection mechanism that is not independent as its members are

appointed by the President. Further, the Minister of Defence has the power to make rules

on how the Board deals with representations made by detained persons. It therefore does

not act as a safeguard against executive abuse of power. Any non-judicial mechanism that

is established to decide on/recommend the release of persons detained under the PTA

must be independent and entities, such as the Attorney-General’s Department, should not

be able to veto its decisions.

Way forward

The proposals shared by the government with SLCC fail to address the fundamental

shortcomings of the PTA. Instead, they propose changes that already exist but are often

observed in the breach.

We note with deep concern that the functioning of the aforementioned committees was

not transparent and the recommendations were formulated without any consultation

with members of civil society who have been working on issues related to the PTA or

persons affected by the law. We call for greater transparency in the reform process from

this point onwards and request the government to inform the public of the process for

consultation and the proposed timeline for reform.

We reiterate that national security cannot be achieved by creating insecurity for already

discriminated against and marginalized communities, and call for the repeal of the PTA.

The repeal of the PTA must also be considered in light of the anti-terrorism and public

security legal framework that Sri Lanka has in place, and the historical abuse of power by

state entities. These entities should not be bestowed with additional power.

The way forward must give due recognition to the protection of physical liberty. Deprivation of physical liberty by the executive must be used only as last resort and strictly require sufficient basis that is determined on objective factors, judicial supervision of such basis, prompt and free access to legal representation including legal aid, prompt trials or release, and an enforceable right to compensation for arbitrary detention. The prohibition of arbitrary deprivation of liberty has acquired customary international law status and constitutes a jus cogens norm which Sri Lanka is duty bound to secure for its citizens.

The balance the government wishes to achieve between personal liberties and national

security can only be achieved through addressing the root causes of conflict and violence.

Attempts to further curtail civil liberties in the guise of national security will only exacerbate the insecurity of all communities and undermine the rule of law and democracy in Sri Lanka.

Signatories

S. Annalaxumy

Bisliya Bhutto

S.C.C. Elankovan, Lawyer and Development Consultant

Philip Dissanayake

A.M. Faaiz

Brito Fernando

Nimalka Fernando

Ruki Fernando

Aneesa Firthous

Amarasingham Gajenthiran

T.Gangeswary

K. Ginogini

Ranitha Gnanarajah AAL

B. Gowthaman

S. Hayakirivan, Director, THALAM

V. Inthrani

Noorul Ismiya

Vasuki Jeyshankar

Dr. Sakuntala Kadirgamar

S. Kamalakanthan – Social Activist

Mahaluxmy Kurushanthan

Kandumani Lavakusarasa, Human Rights Activist

Jensila Majeed

Buhary Mohamed, Human Rights Activist

Juwairiya Mohideen

Jaabir Raazi Muhammadh, Chairman, Voices Movement

P. Muthulingam

Thangaraja Prashanthiran

Dorin Rajani

Maithreyi Rajasingham, Executive Director, Viluthu

A.R.A. Ramees

V. Ranjana

Anuratha Rajaretnam

K.S. Ratnvale

Yamini Ravindran, AAL

Kumudini Samuel

Thurainayagam Sanjeevan

Shreen Saroor

Ambika Satkunanathan

Rev Fr S D P Selvan

S. Selvaranie

Vanie Simon

P. N. Singham

Usha Sivakumar

N. Sumanthi

Vani Sutha

Ermiza Tegal

S. Thileepan – Social Activist

P Vasanthagowrey

Rev Fr Yogeswaran

Adayalam Centre for Policy Research

Alliance for Minorities

Centre for Human Rights and Development

Centre for Justice and Change

Eastern Social Development Foundation

Families of the Disappeared

Forum for Plural Democracy

Law and Society Trust

Mannar Women’s Development Federation

Rural Development Foundation

Tamil Civil Society Forum

Viluthu

Women’s Action Network