Excerpts form the report of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka to the Committee Against Torture, October 2016. Sub headings are from the SLB.

Introduction

- Following the 19th amendment to the Constitution in 2015, which established the Constitutional Council constituting members of political parties as well as civil society mandated to appoint members to the independent commissions, new members were appointed to the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka in late October 2015.

- In 2007 the Commission was downgraded to B status by the International Co-ordinating Committee of National Human Rights Institutions (ICC) for failure to adhere to the Paris Principles. Since the independence of the Commission was enhanced following the 19th amendment to the Constitution, and the reasons for the downgrading are being addressed, the Commission is in the process of applying for A status.

- The Commission as the National Human Rights institution submits this report for the review of the fifth periodic report of Sri Lanka by the Committee Against Torture in response to the call by treaty bodies. This report is based on complaints received by the Commission, recommendations issued by the Commission, visit reports to places of detention and other state institutions where persons are deprived of liberty, studies undertaken by the Commission and state documents in the public domain, such as court records and judicial decisions.

- Since being appointed twelve months ago the Commission has initiated a process of reviewing, re-structuring and reforming its institutional structures and processes, and strengthening its human resource capacity, which restricts its ability to submit a comprehensive report. Hence, this report responds to key issues arising from the Concluding Observations of the Committee issued in 2011, and the questions raised in the List of Issues by the Committee.

- The Commission calls for the amendment of the definition of torture in Section 12 of the Convention Against Torture Act and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Act no 22 of 1994 to expand the definition of torture to all acts of torture, including those causing severe suffering, in accordance with article 1 of the Convention Against Torture.

- The Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka has requested information from the Attorney-General’s Department on the number of indictments filed and convictions under the Convention Against Torture Act, but to date is yet to receive the requested information.

- The Government ratified the Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearances on 25 May 2016. Adoption of enabling legislation, which is required to give effect to the Convention at the national level, is still pending.

Torture

- The Commission following its appointment in late October 2015 found there have been long delays in dealing with torture complaints, with the sense these cases were not prioritised in the past, and has taken action to expedite investigations. Further, due to weak documentation and archiving systems, hamper its ability to provide greater breakdown of data. The Commission is streamlining its inquiry and investigation processes, including training for staff, mechanisms ensure staff accountability and formulating procedural manuals. To support effective inquiry and investigation the Commission is adopting measures to strengthen its documentation and archiving systems and procedures as well.

- The Commission is in the process of establishing a ‘Custodial Violations Unit’ in its Investigations and Inquiries Division in order to build specialized capacity in that regard, and to also expedite investigations and inquires of such complaints. The Commission shall refer all findings of torture to the Attorney- General’s Department for prosecution under the Convention Against Torture Act No 22 of 1994.

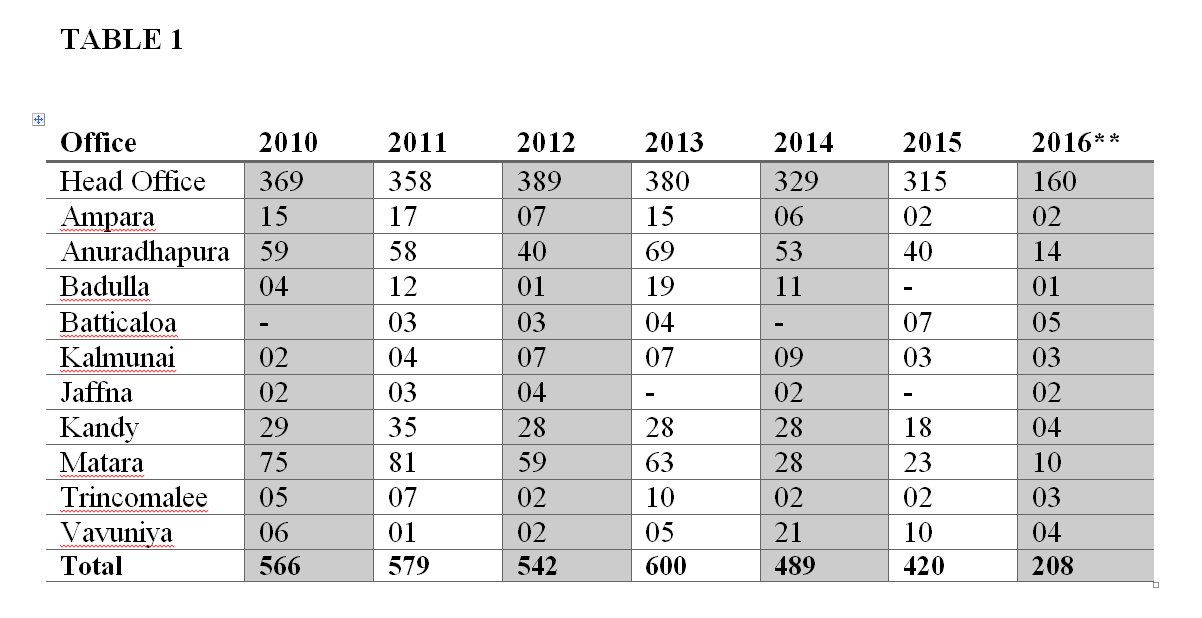

- Based on the statistics at the Commission’s disposal, which are provided below, the Commission recognizes torture to be of routine nature that is practiced all over the country, mainly in relation to police detentions. The statistics of torture complaints received are as follows:

- The complaints received by the Commission illustrate that torture is routinely used in all parts of the country regardless of the nature of the suspected offence for which the person is arrested. For instance, those arrested on suspicion of robbery, possession of drugs, assault, treasure hunting, dispute with family/spouse, have been subjected to torture. The prevailing culture of impunity where those accused of torture is concerned is also a contributing factor to the routine use of torture as a means of interrogation and investigation. Usually, complainants are from low-income groups. The Commission has received complaints of persons sometimes being arrested with family members, sometimes arrests being made due to mistaken identity, and torture used to elicit information or to punish. For example, in a case from Weligama in the Southern Province the complainant was beaten, threatened at gunpoint and taken to the police station by three policemen dressed in civilian clothing in front of his family due to mistaken identity, which was revealed when his identity card was checked at the police station. The medico-legal report confirmed his injuries.

- Some complaints refer to torture being used for settling personal scores by the police. For instance, a gem merchant from the Sabaragamuwa Province was threatened to pay a share of his earnings to the Officer-in Charge (OIC) of the police station as the officer had accepted money from the complainant and allowed him to engage in gem mining without a license from the relevant authority. Thereafter, the man was attacked by fifteen police officers by poles and by hand. The medical report found fifty-five bodily injuries of which thirty-seven were found to have been caused by being beaten with sticks made from the cinnamon tree, which are thick and strong. In another case, from Hanwella in the Western Province, the OIC and several police officers in civilian attire beat the victim and took him to the police station due to the complainant refusing to rent a restaurant he owned to the OIC. The OIC threatened him saying that he would place explosives in a building or vehicle belonging to the petitioner, and arrest him. The medical report corroborated the complainant’s narrative.

- Torture is used not only during the process of interrogation but also during the process of arrest. For instance, in Madawachchiya, North Central Province, the complainant intervened when he saw two persons in civilian attire beating his neighbour. Since the said persons had identified themselves as policemen, the petitioner asked for their identification documents. Thereafter, the so called policemen (who were later found to be police officers), threatened him by holding a weapon his neck, assaulted him and took him to custody along with two others and accused the petitioner of possessing illicitly brewed alcohol. The complainant’s daughter was also verbally abused when she pleaded not take her father to police station. In another case from the Southern Province, two children – fourteen and sixteen years – were assaulted with a rifle and a thick, hard stick from the albeasia tree, which is used for fencing, on suspicion of damaging a three-wheeler and were instructed to run to the police station holding their bicycles. There was no complaint of assault while in the police station. Medical examination found the wounds were compatible with the given history.

- Common methods of torture include, undressing the person and assaulting using the hand, foot, poles, wires, belts and iron bars, beating with poles on the soles of the feet (phalenga), denial of water following beating, forcing the person to do degrading acts, trampling and kicking, applying chilli juice to eyes, face and genitals, hanging the person by the hands and rotating/and or beating on the soles of the feet, crushing the person’s nails and handcuffing the person for hours to a window or cell bar. Increasingly, physical torture is perpetrated using methods that cannot be easily detected by medical personnel. An example is of an arrest in March 2016 by the Kalutara North police in the Western Province for possessing illegal drugs where the person was subjected to torture while blindfolded. He was assaulted all over the body, was thereafter hand cuffed to a window. The medical examination found twelve wounds including loss of front tooth, abrasion wound on wrist, and abrasion and contusion wounds on the body.

- Psychological torture includes, taunting and using expletives in the presence of the public and other police officers, and scaring them by threatening the well-being of family members, especially children. In the case of Sajith Suranga SC (FR) Application No: 527/2011, a seventeen year old was arrested in the Southern Province during a period when a phenomenon/persons called the grease devil were causing fear in rural communities and displayed to the crowd by the police as the grease yaka. He was thereafter taken to the police station and assaulted with batons on the face and chest and legs, after which his hands held around a pillar and he was assaulted again on various parts of the body for an hour. A book was placed on his head and it was repeatedly hit with a baton. He requested water but was not given any. The Supreme Court found, based on medical report which was a result of the Commission referring the complainant to a judicial medical examination, that the complainant exhibited many psychological consequences of trauma such as, recurrent distressing dreams, insomnia, hyper vigilance, social withdrawal reliving incident, depression and suicidal thoughts, and loss of self –esteem. This incident led to him dropping out of vocational training programme in which he was enrolled.

- In September 2015, where a four-year old girl was raped and murdered causing public uproar, the police arrested a seventeen-year old boy and a thirty-year old man, both of whom were subsequently released. However, both have complained of being subject to physical and mental torture by the police officers who arrested them. Both persons have instituted fundamental rights petitions before the Supreme Court. Subsequently another man who was arrested was reported by the police to have “confessed” to the rape and murder. However DNA tests exonerated him and eventually his brother was arrested and convicted for the rape and murder.

Failure to follow due process during arrest

19. A feature common to many complaints, and one regularly detected through the Commission’s investigations is the failure to follow due process during arrest, with one of the most common violations being failure to produce the person before a magistrate within twenty-four hours and altering the time of arrest in their official records. Under normal law, an arrested person can be detained only for twenty-four hours (with a few exceptions), after which the person has to be produced before a judicial officer. For example, recently our officers detected such instances in Peliyagoda (Western Province) and Jaffna (Northern Province). In the latter instance since the man’s whereabouts following arrest were unknown for six days the Commission informed the Inspector-General of Police and the Minister Law and Order of this case and requested an immediate inquiry be held and remedial action taken. To date the Commission has not received an update on the action taken.

Detention under Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act

- Given the law is rigid and the periods of detention are lengthy and without judicial review, which creates the context to encourage abuse and torture the Commission has focused special attention on the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act no 48 of 1979. On 18 May 2016 the Human Rights Commission issued Directives on Arrest and Detention under the PTA following the spate of arrests under the PTA beginning April 2016. This was done as the Commission received complaints both from detainees and their families that due process was not being followed during arrest and detention. These Directives were incorporated in the Directives issued by His Excellency the President. Following the issuance of the Directives by the President, the Commission was informed by the Director, Terrorism Investigation Department (TID) under oath, that it had not yet received said Directives and that he was unaware of the same. The Commission has written to His Excellency the President requesting that Directives be given to the police in order to operationalize them.

Since April 2016 the Commission has received complaints from family members, as well as those arrested and detained under the PTA, and in some instances has found that that due process was not followed, which creates space for torture- this included failure of officers to:

- identify themselves

- wear uniforms

- inform the person of the reason for the arrest

- issue an arrest receipt or receipts were issued in a language not understood by the detainee or his/her family.

- inform the family the place to which arrested person was being taken

- use official vehicles

- issue receipts for seizure of private property

The Commission has received complaints of persons being held at detention centres that are not gazetted, which creates opportunity for torture, which the Commission brought to the attention of all relevant authorities. Upon inquiry it was revealed the places at which persons were held for at least twelve hours were offices of the TID but not gazetted detention centres. The TID has only three gazetted places of detention – Boosa, TID Vavuniya and TID Colombo. Some detainees mentioned they were told to sign forms and statements, which were in a language they did not understand.

Thirteen persons arrested under the PTA since April 2016 have complained of ill-treatment and torture, either at the time of arrest and/or during initial interrogation following arrest. Methods of ill-treatment and torture reported to the Commission include beating with hands, plastic pipes and sticks, being asked to strip and genitals being squeezed using plastic pipes, forced to bend and beaten on the spine with elbows, being strung upside down on a hook/fan and beaten on the soles of the feet, being pushed to the ground and kicked and stepped on, inserting pins on genitals, burning parts of the body with heated plastic pipes, handcuffing one hand behind the back and the other over the shoulder, inserting a stick between the handcuffs and pulling the hands apart. Detainees also stated they were handcuffed and blindfolded when transported to detention facilities and during this period, which could amount to at least six to eight hours, were not allowed to use sanitation facilities.

The TID has been informing the Commission of those arrested under the PTA as per section 28 (1) of the Human Rights Commission Act. Since May 2016 transfers of detainees between places of detention has also been informed to the Commission.

Persons held in administrative detention under the PTA, as well as lawyers have complained of difficulties of lawyers visiting and being able to consult with detainees in private. Lawyers have stated they have to submit written requests to the Director TID to seek permission to visit a detainee and while some are granted access, a number of others state they have never received a response despite sending repeated requests.

In response to the Committee’s question regarding those who remain in detention, based on the statistics at the disposal of the Commission obtained from the Department of Prisons, as at May 2016, of the one hundred and eleven (111) persons who still remain in remand custody under the PTA, twenty-nine have not been indicted. It should be noted this does not take into account those arrested and remanded thereafter when there were a spate of arrests under the PTA. The longest period a person has been on remand without indictment being filed is fifteen years. The longest period a trial has been on-going is since 2002, i.e. fourteen years. Forty-one persons are appealing their sentences under the PTA with the longest period the person has been awaiting a decision being fourteen years.

Right of the suspects in accessing lawyers

- Owing to difficulties experienced by suspects in accessing lawyers, the Inspector General of Police made rules under the Police Ordinance cited as Police (Appearances of Attorneys-at-Law at Police Stations) Rules 2012 recognising the right of a lawyer to represent his/her client at a police station and requiring the officer in charge of the police station to facilitate such representation. The Rules were adopted as a result of a settlement reached in the Supreme Court in a Fundamental Rights Application. These rules effectively recognised the right which all persons including suspects have to access their Attorneys-at-law at any time, including the period immediately after arrest and while being in detention. However, despite these rules difficulties have been experienced by those detained by the TID and Criminal Investigation Department. In 2016 August the Government Gazetted a Bill proposing to amend the Criminal Procedure Code, allowing a suspect access to his lawyers after the statement of the suspect are recorded.

Since the right to legal representation is integral to ensuring torture does not take place, the Commission requested the Government to withdraw the Bill proposed amendment deprives suspects of access to lawyers between the time of arrest until the time of the conclusion of the recording of a statement. The Commission has pointed out that the amendment would pave the way for increasing possibilities of torture in custody and is in violation of Sri Lanka’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). This also adversely impacts the right of persons to fair trial. Since the issuance of the statement of the Commission the government has delayed the passage of the Bill. However, no definitive announcement has been made with regard to continuing the status quo that permits the right to legal representation immediately after arrest.

- There is a shortage of Tamil interpreters in the justice system as well as at police stations, which can adversely impact upon the due process and fair trial rights of detainees.

Examinations by Judicial Medical Officers

- Where independent medical examinations by Judicial Medical Officers are concerned, although there are sixty-five allocated vacancies for Judicial Medical to date there are only thirty-five JMOs, with only three consultants based in Colombo. The others are Medico-legal officers who have not specialised in the subject area but have been given one month training. It has come to the attention of the Commission that since junior officers are on duty after hours often the police bring persons for examinations during this period. Although every person who is examined by a JMO is provided a receipt with the reference number, name of the examining officer and date of examination, PTA detainees in particular often did not possess this receipt. Even though persons are produced before the JMO by the police upon the request of the Commission, it is not always done within twenty-four hours of the request. Given time is of the essence where recording torture injuries are concerned this hampers the ability of the Commission to conduct an effective investigation.

The Commission has had a very positive and fruitful discussion with the Chief JMO Colombo, and will be establishing a collaborative relationship with the College of Forensic Pathologists with the aim of engaging actively with them to address custodial torture.

TID detention centers

- Another example is the cells at TID Colombo measuring five feet by four feet and detainees have to bring their own mats, pillows and other personal effects. The cells have very little natural light and ventilation. While the cells are larger at Boosa there is virtually no ventilation or natural light and cells are dark even during the day. Detainees at Boosa stated locked in the cells most of the day and allowed to go outside only during mealtimes. If they wish to use the sanitation facilities they stated they have to call out to the officer on duty or bang on their doors. At night they are reportedly not allowed to use the sanitation facilities. Detainees at TID Colombo mentioned that following interventions by the Commission they are being provided adequate and nutritious meals at regular times. They also stated they are allowed to meet family members and converse with them freely.

- There is no separate facility for women detainees at TID Colombo, with a woman detainee being held in different office rooms during her period of detention.

Deaths of suspects in police custody

- There continue to be reports of . In 2012 the Commission received nine complaints, three in 2013, eight in 2014, seven in 2015 and in 2016 two complaints to date. When a death of a suspect in custody is reported investigations are often conducted by the very same police station where the suspects have been held in custody. Prior to 2015, there have been numerous instances of deaths in police custody under suspicious circumstances. In certain instances the authorities have not conducted independent investigations of custodial deaths. In order to prevent a recurrence of these suspicious deaths, there is a need to establish an independent investigation unit within the Police Department, which can immediately investigate custodial deaths. It is also advisable that in such instances the Post Mortem Examination be conducted outside the area in which death occurred as there have been instances of collusion between medical personnel and culpable police officers.

Special needs of children in detention

- With regard to the special needs of children in detention, there is no clear demarcation of services provided by different types of institutions and many were compelled to take on multiple roles due to a dearth of services in the district or province. For instance, Remand Homes function as a space for children accused of crimes, but it also function as a Safe House for children who were survivors of child abuse, until the judicial process is completed. Certified Schools functioned both for the rehabilitation of children convicted of crimes, as well as for survivors of abuse. In one institution the Commission visited, children (16-21 years) were not segregated from adult prisoners who were also resident at the same institution due to inadequate infrastructure.

There are several shortcomings in the admission procedures and recommendations made by the Department of Probation and Child Care Service, such as failure to undertaken medical and psychological assessments when children are admitted. In one of the Centres the Commission visited, a child had an injury as the police had hit the child with a baton. It seemed that there was no medical attention given to the child during the two weeks since the child was brought into the Centre. This in turn has resulted in children having physical injury without any medical attention given.

Children who are less than twelve years are also being admitted to detention and remand homes. In one case an eleven-year-old boy was being held in an institution. His father is in prison as he was suspected of raping a girl from the neighbourhood. The family need four thousand rupees (Rs. 4000) to pay his bail, but his mother is a housewife and has no income. He can sing well so he started singing in public bus to earn money for the family and secure his father’s release on bail. He was arrested by the police one day while singing in a bus, held at the police station for a day and was sent from there to a Remand Home. In a number of instances children are also transported with adult prisoners.

Rehabilitation under the Prevention of Terrorism Act

- With reference to the Committee’s questions regarding rehabilitation under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, since 2011 persons being held at detention centres such Boosa (maximum period of detention eighteen months), and remand prisoners (remand can be extended indeterminately) have been transferred to rehabilitation centres. There have also been instances of persons who were held at rehabilitation centres (maximum period of detention twenty-four months) being transferred to detention centres, such as Boosa, and prisons. Such transfers result in the extension of the period an individual is held in prolonged, indefinite administrative detention.

In 2015 and 2016 it was found the rehabilitation process was being used to “reform” persons who were thought to not passed security checks required for certain state employment, such as Grama Niladari officers (village officers). In May 2015 and March 2016, sixteen and six GN officers respectively in the North were informed by the Ministry of Home Affairs, which according to the law has no authority to order persons to rehabilitation, they would have to undergo rehabilitation. In total eleven persons completed this programme and were released after three months- seven women and four men. Of the seven women, one woman had a baby three months ago prior to being sent to rehab and hence her baby along with her mother lived with her at Poonthotam.

It has been brought to the notice of the Commission that those on remand under the PTA without being indicted are being requested whether they are willing to go to rehabilitation and upon signing consent letters are sent to rehabilitation. In these instances, if there is no credible evidence against the person to indict, the criteria upon which the persons are being sent to rehabilitation are unclear. In a number of other cases court records reveal the TID has stated in court that the Attorney-General (AG) had ordered the person to rehabilitation although in law the AG is not the decision-making authority in this regard. In this regard too it appears the person’s consent was not obtained, as there have been many cases where persons have refused in court to be sent to rehabilitation.

Although rehabilitation is within the purview of the Ministry of Resettlement, the power to determine the period of rehabilitation lies with the Secretary, Ministry of Defence. The Officer- in-Charge of the rehabilitation centre is a military officer and all other staff too appear to be military officials. Additionally, the Attorney-General’s Department and other entities such as the Ministry of Home Affairs are also making decisions regarding rehabilitation. Hence, there is lack of clarity regarding the making authority responsible for the implementation of the process. Poonthottam is the only remaining rehabilitation centre where as at 15 October 2016, 18 men were being held.

HRC SL calls for the repeal of PTA

- In response to the Committee’s questions on persons being compelled to confess to a crime under torture with specific reference to the PTA, the Commission recognises the PTA does not adhere to international human rights standards and while calling for the repeal of the Act issued a statement calling upon the government to ensure national security legislation which is reportedly being drafted include certain core elements to ensure it adheres to international human rights standards. The statement reiterated the need for judicial review of detention, the importance of the right to fair trial, and the dangers of enabling the admissibility of confessions made to police officers of senior ranks which, coupled with prolonged periods of administrative detention, creates space for torture and ill-treatment. The Commission has requested the government thrice to share the draft national security legislation with the Commission to enable it to fulfil its mandate as per sections 10 (c ) and (d) but is yet to receive it.

Harassment and intimidation of civil society and human rights defenders

- With regard to the Committee’s questions relating to the harassment and intimidation of civil society and human rights defenders, the Human Rights Commission has received complaints from civil society organisations regarding persons who have stated they are intelligence or officers of the CID/TID and have requested information about the organisations and their activities, particularly when these persons are engaged in or following their participation in public demonstrations or events. Further, the Commission has received complaints from persons who have appeared before the Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms that they have been subjected to surveillance and intimidation. For instance, Ruki Fernando, a human rights activist was detained at the airport on 1 October 2016 where he was questioned by the TID about cases pending against him, destination of travel, purpose of travel, his work and personal details, including addresses and phone number, details of family members etc. One of his lawyers who was also travelling with him requested to be allowed to be with him during the questioning but was refused. He was not told the reason for the detention and interrogation.

– REVIEW OF THE 5th PERIODIC REPORT OF SRI LANKA, October 2016 Read the full report as a PDF:hrc-sl-report-to-un-cat or online here at UNCAT