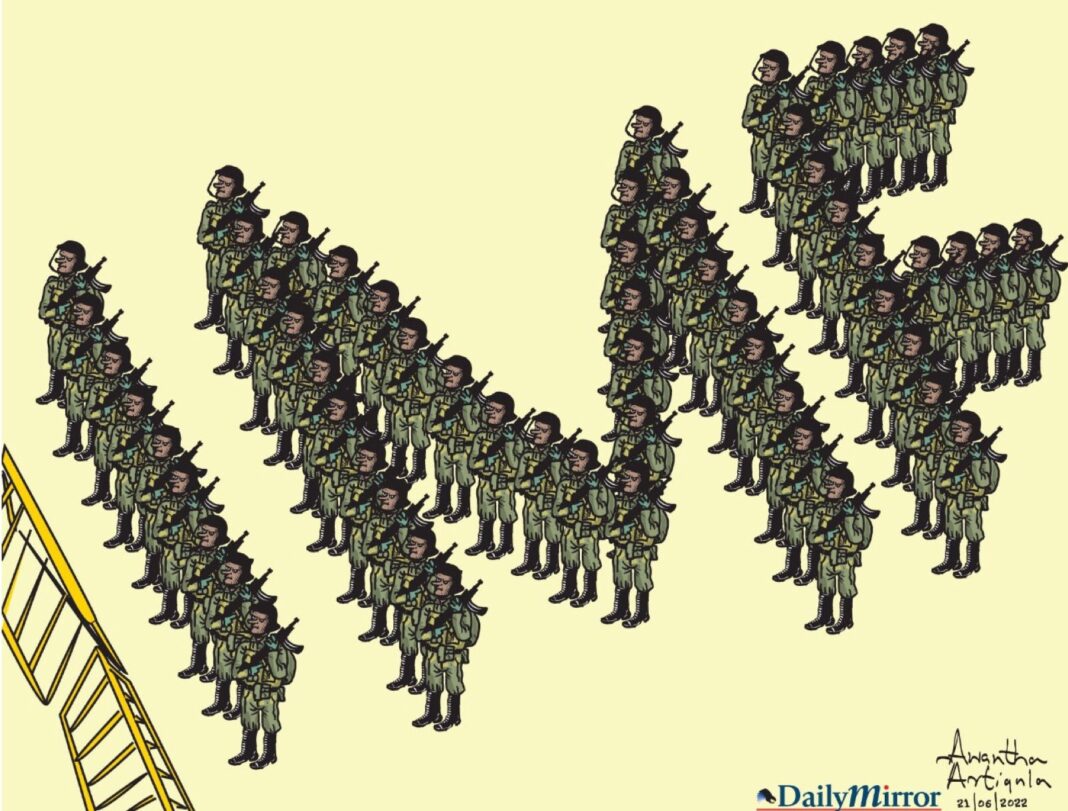

Caroon: Sri Cartoonists have taken IMF to the task!

(Part 2) March 20, when the IMF Board approved an Extended Fund Facility for Sri Lanka, now seems a long time ago. For many people this felt like a major step toward the resolution of the country’s economic problems. It certainly seemed to indicate that there was international agreement on how to deal with the government’s bankruptcy. Some people will have been surprised to see that on April 17, in Washington DC, the government and its creditors launched formal negotiations on what actually to do about the debt, how much will be written off and how the cost of those write offs will be distributed among the many creditors. Previous agreements were just about principles. Now the details have to be decided and signed off before most of the IMF loan can be released. Every report on these Washington negotiations emphasises that China, Sri Lanka’s largest single creditor, was not present on April 17. Some commentators suggest that the meeting has been called to put pressure on China to become seriously engaged. They also point out that time is short. The agreement with the IMF might be aborted. In other words, the IMF has not actually come to Sri Lanka’s rescue and may not be able to do so. This is not because the IMF lacks willing but because the international institutions and arrangements to deal with the problem are in a mess.

No international law on bankrupt governments

When companies go bankrupt, they are wound up or restructured under national law. There is no international law to deal with bankrupt governments. Until recently, the world has muddled through to case by case solutions with an ad hoc combination of legal contracts and informal understandings. That combination worked in large part because it was run mainly by the more influential Western nations, through arrangements labelled Paris Club in the insiders’ jargon. The IMF was broadly the secretariat to the Paris club, enjoying considerable influence all the time it enjoyed the trust of the Western nations, but not ultimately calling the shots.

Owners of the debt have change

Why do Paris Club arrangements no longer deliver either for Sri Lanka or for the growing list of governments of low and middle income countries that are in debt distress? The main reason is that the owners of the debt have changed. When the 1980s debt crisis hit many low income countries, most of their debts were owned by the Paris Club, i.e. by a combination of Western governments, Western banks and multilateral organisations very much influenced by Western governments. Sri Lanka’s debts, like those of many other contemporary distressed governments, principally take the form of either loans from Chinese banks or international sovereign bonds (ISBs). ISBs were originally sold on international financial markets by the Sri Lankan government. The government received a capital sum and in return agreed to pay a fixed rate of interest to the bondholder. The government became bankrupt in early 2022 when it finally admitted that it did not have the money to pay all the interest due to the bondholders. In the meantime most these bonds have been sold on, often repeatedly.

The Paris Club no longer includes or has much direct leverage over the organisations to which the governments of many poorer countries, including Sri Lanka, owe the most money. The dispersion of the ownership of Sri Lanka’s ISBs could become a problem if the current court case in the US goes against the government of Sri Lanka. American law in this area remains murky and subject to re-interpretation. Otherwise, all the signs are that the bondholders will be cooperative in agreeing to accept a write-down of the value of their bonds. Many of them purchased those bonds speculatively, at a heavy discount to face value, after it became clear in 2020 that the government of Sri Lanka could not redeem them in full because it was heading for bankruptcy.

$80 billion of Chinese loans gone bad

China is a much bigger potential obstacle to a quick agreement about which creditors will accept how much of a haircut. This is not just because the government of China, understandably, is unwilling to accept the leadership of the Paris Club, and wants new international arrangements that give it the influence it believes it merits as a major creditor; it is also because China’s banks have become a major source of lending to poorer countries and, now that many of these loans have turned bad, collectively face bankruptcy threats of their own. The Rhodium Group, a New York research organisation, has just estimated that, over the past three years, almost $80 billion of Chinese loans for roads, railways, ports and other infrastructure given under the Belt and Road Initiative have been renegotiated or written off. The government of China needs an effective international mechanism to deal with the debts of bankrupt governments. But it wants a mechanism which gives it, the biggest creditor, more influence. In the meantime, it does not intend to be generous in writing off the debts it is owed because it cannot afford to do so.

The negotiations about the debts of the government of Sri Lanka are enmeshed in complex international geo-politics. Understandably, the IMF has kept quiet about this and emphasised the potential domestic political problems: “Risks to program implementation are high, given adverse initial conditions, political risk, a complex debt restructuring with a potential for delay, ambitious fiscal consolidation, large downside risks to the baseline scenario, and Sri Lanka’s weak track record for reform and program implementation” (From p.30 of the formal request for support approved by the IMF Board). Domestic and international politics will interact, possibly in surprising ways. Internationally, the government of Sri Lanka will need to be friends with everyone, especially with the West, with China and with India, which is taking a leading role in the current negotiations. The government would be in a stronger position in these negotiations if it enjoyed significant levels of support and trust from the public and opposition politicians. It does not, and seems likely to continue on its current path of demanding allegiance and quiescence on grounds of national necessity, and accusing critics of disloyalty to the country.

Implications for democracy are negative

The immediate implications for Sri Lankan democracy are negative. The country will not be consulted about how the government is trying to deal with and influence these complex interactions between the IMF-Sri Lanka programme, debt restructuring for Sri Lanka and the fragile and somewhat dysfunctional international arrangements for dealing with sovereign bankruptcy. This is partly because the current government in temperamentally disinclined to be transparent or to consult but also because it will be playing a relatively weak hand in a complex international game, and would genuinely find it difficult to consult with domestic political forces that do not trust it. To this extent, the pessimists who see a direct contradiction between the IMF agreement and internal democracy are correct. But only to this extent. There are other elements of the IMF agreement that could be embraced to provide a useful boost to both progressive public policies and democracy.

IMF and Social Safety Net

The IMF agreement does not mandate the savage public spending cuts that some have feared. That is principally because, aside from selling off loss-making public enterprises and cutting some big public infrastructure projects, there is currently little scope for cutting public spending without putting many (poorly-paid) public sector workers out of a job. That is politically too provocative. The IMF documentation suggests that it places higher priority on what it terms social safety nets i.e. direct cash transfers from government to the poorest families. The issue appears in the sixth line of the press release that the IMF issued on March 20. It is treated in some detail in the 131 page technical document that forms the basis of the agreement. The messaging is clear. Whatever steps the current government has taken to protect the poor have been more than eroded by inflation (p.9). Spending needs to be increased in 2023 to meet an indicative target. It is a structural benchmark for the whole programme that the Sri Lankan parliament approve a whole new social safety net scheme by May 2023 (p14). There are four pages of more technical material in Annex IV, including an incisive comparison with other middle income countries, pointing out how miserly are the transfers that the government makes to poor Sri Lankans.

The IMF has placed much more emphasis on the need to spend public money to protect the poor than have most Sri Lankan politicians and political activists. We have seen plenty of protests recently about the increase in personal income taxes by people who are certainly hard pressed but not in most cases forced to go hungry. Where are the protests about the failure of the current government to live up to the commitments it made last year to protect those who really face destitution? It is probably a sign of how little the current government is really interested in this issue that in his address to Parliament on 22 March to celebrate the IMF agreement, President Wickremesinghe devoted just 20 of his 3,174 words to social safety nets, and those only near the end of his speech. That could be taken as an indicator of how important it is for progressive organisations to get behind this issue and pressure the government to live up to its commitments.

Role for progressive forces

There is another element in the IMF agreement that relates more directly to the future of democracy. The key paragraph, from the main IMF document, reads “An IMF governance diagnostic mission has started to assess Sri Lanka’s governance and anti-corruption framework. The diagnostic report will be published by September 2023 (structural benchmark). The report’s findings will help identify specific priority and time-bound reforms to be implemented under the program” (p.23). Many Sri Lankans will view this provision as outrageous and a vindication of their belief that the IMF agreement is an instrument through which international finance will seek to get control of the Sri Lankan economy. What right does an organisation with a purely fiscal and financial mandate have to investigate the governance of Sri Lanka and to suggest, urge or decree how governance should be reformed? Surely this is the very antithesis of democracy and of national sovereignty? My answer is not necessarily; the potential gains from IMF engagement in these sensitive issues might much outweigh the costs but only if progressive political forces in Sri Lanka seize the opportunity to shape what actually takes place under the rubric of an IMF governance diagnostic. There are two main reasons why I suggest that progressive forces might like to sup with this particular devil.

First, a strong nudge from the IMF could be very helpful because the set of issues that their governance diagnostic is addressing – issues of corruption, lack of transparency in the uses of public money, widespread failure by recent governments to follow their own rules about the management of public money – have become increasingly central to the decline of democracy and constitutionality in Sri Lanka but have not received adequate attention from domestic democrats. There is no consensus on the causes of the decline of democracy and constitutionality over recent decades. Some point fingers at particular leaders or at elite leadership in general. Others cite larger forces like (international) capitalism, the gradual militarisation of the state that can be dated back to the response to the 1971 JVP insurgency or the exploitation of ethnic and religious differences and competition for educational opportunities and public sector jobs. All played some role.

IMF may not deliver governance diagnosis

In my view, one of the more important recent causes lies in the discovery by those in power, especially since the defeat of the LTTE in 2009, that the very strong executive power that had been gradually been established could be used to by-pass all kinds of fiscal and expenditure rules and procedures, and to loot the state. Verite Research has documented some of the tricks used. This looting goes along with a long term decline in the competence, capacity and professional autonomy of the public fiscal institutions that are supposed to uphold good management of public money, notably the Ministry of Finance and the Auditor General, but also the legislative committees (Committee on Public Accounts, Committee on Public Enterprises) and even the Central Bank. I don’t think we can restore effective democracy until we can find new, binding ways of preventing people who win elections from continuing to loot. If they can loot, they have both a strong incentive to remain in power and the resources to buy off all the people and institutions that might stop them. These are far from the only issues that matter for democracy. There are many others that are equally important, including human rights, extra judicial killings, judicial independence, ethnic majoritarianism and the abuse of the police for political purposes. But these issues of fiscal and financial rules and procedures are not only important but are complex and technical and do not get much routine coverage in places such as Groundviews. It would be good to have the IMF drawing attention to the problem and suggesting remedies.

The second reason I would be willing to sup with the IMF devil is that I have no fears that the IMF is about to take control of the governance of Sri Lanka. Indeed, my concern is the very opposite: that the IMF will produce a governance diagnosis, that may or may not be made public, but the IMF itself will not be at all insistent that it be taken seriously and will be all too inclined to leave the report and retreat to Washington at the first sign of serious push back from the government. Why is the IMF likely to be so timid? One reason is that it is actually a very small organisation that specialises in monetary, financial and fiscal issues. It is not set up exercise much influence in any of its 190 member countries. It currently has only about 2,700 employees, which is one seventh of the number of people who work for the World Bank. Its staff are cautious technocrats – economists, financial specialists, lawyers and accountants, much better suited to sitting at desks doing financial calculations than undertaking the kind of political networking needed to rule. The other reason is closely related. The IMF is simply not used to undertaking the kind of governance diagnosis that it is now doing on Sri Lanka. This is a little outside the organisational comfort zone and probably at the margins of its competence. Its natural instinct will be to hand over a report to the government and back off, especially if vigorously challenged by the government. And that is why civil society and progressive politicians in Sri Lanka need to get their challenges in first. This governance diagnosis is already underway. Sri Lankans should demand of the IMF transparency and serious engagement with representatives of the nation other than the government. They should be ready with their own diagnoses. In the longer term, they should be mobilising to critique the IMF report and, above all, to keep the government’s and the IMF’s feet to the fire on the issue of re-establishing effective management of public money in the public domain.

The IMF agreement is not in reality a done deal. It is going to be argued over and likely renegotiated for several years to come. The less those negotiations are monopolised by the government and the IMF, the better are the outcomes likely to be for Sri Lanka and Sri Lankans.

Making the IMF Work for Sri Lankans ( Part 1)

The government of Sri Lanka is negotiating a large conditional loan from the IMF. A formal agreement is likely to be signed within weeks once all the main creditors provide the IMF with adequate assurances that they will write off some of the government’s outstanding debt and will not seek to exploit any future economic uplift to demand priority repayment of their own loans.

But Sri Lanka’s politicians are very divided over the idea of signing any agreement with the IMF. On the one side, the government is asserting that an agreement is essential, that it should not be considered a political issue and that the government itself needs to be given a great deal of policy discretion so that it can meet IMF demands. On the other side, most of the political left is opposed to any agreement with the IMF, commonly on the grounds that this in reality would constitute another (neo-liberal) attempt by coalition of international finance capital, the IMF and the US government to take control of economic policy and extract yet more profit from the Sri Lanka people. Another left argument is that Sri Lanka has entered into many IMF programmes before. None of them fundamentally cured Sri Lanka’s economic problems so there is no reason to expect this one to work.

This political and ideological polarisation is counterproductive and likely to cost Sri Lankans a great deal in term of increased hunger, higher levels of mortality, lost education and long term poverty. My best guess is that the IMF agreement will be signed but the government will not stick closely to its side of the bargain. It will not raise the additional revenue promised, cut corners in various ways, continually promise to perform better in the next financial quarter and do its best to keep the IMF in the dark about some key economic and fiscal statistics. The IMF will tolerate this for some time, not least because it has a strong self-interest in not appearing to be excessively tough on small countries and in not terminating programmes while they appear to have some chance of success. But eventually one side or the other will call time on the agreement. That prediction is rooted in history. Globally, 38% of IMF programmes were terminated prematurely over the period 1980-2015. The historical figure for Sri Lanka is a little higher, and close to 50%. Over the 54 year period from 1965 to 2019, Sri Lankan governments signed 16 agreements for IMF assistance. Those agreements were in place for 28 years. Seven of them were terminated early. The most recent agreements were in 2003, 2009 and 2016. In each case the government committed to increasing public revenue as a proportion of GDP. In each case, the revenue targets were missed by a mile. It is already clear that the revenue targets for 2023 set by the current government in preparation for the next IMF agreement are likely to be undershot by around 10%.

An agreement with the IMF in 2023 that sputtered along for two or three years before termination would not be the worst possible outcome for Sri Lanka. The country will at least have received a large initial injection of foreign exchange to help revive the economy. But neither would it be a good outcome. Important reforms, including revenue reforms, will be far from complete. The government will again sink in the credit ratings and find it hard to borrow foreign exchange at reasonable rates. We could be back to severe import restrictions, fuel queues, and fertiliser scarcity and thus to higher levels of undernutrition, increased mortality, more lost schooling and deeper poverty.

There is a better way. That necessarily involves some kind of agreement with the IMF. The economy is greatly underperforming and the people suffering because the government has no access to the credit it needs to import sufficient food, fertiliser, fuel and all those other things needed to get the economy humming again. At present there is no alternative source of credit. Private capital will not lend because the government is in serious default on its existing loans. Private lenders may come back once they have sufficient assurance, as measured mainly the existence of an IMF agreement, that the government is on a sufficiently stable fiscal path that it will eventually be able to repay any new loans that are granted. Official lenders such as China, India, Japan, the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank take essentially the same view. The underlying dynamic is simple: no potential lender, public or private, will loan money to a government that has no prospect of raising sufficient revenue to repay the loans and the interest at some point in the future and/or shows no serious sign of beefing up its revenue machinery to be able to repay. That dynamic will remain even if various great powers and global organisations surprise us and write off a large proportion of the government’s current outstanding debts.

The key term is however some kind of agreement with the IMF. There is much more scope for Sri Lanka to negotiate about this than either the current government or the left suggest. The IMF has become a much more empathetic, pragmatic and flexible organisation than it was when it earned a reputation for rigid and heartless insistence on austerity and public spending cuts as a cure for all macroeconomic problems. The IMF also knows that its country programmes often fail because they lack domestic political support and because they are often badly designed; the governments on the receiving end rely too much on the IMF but the IMF does not have detailed country knowledge. The IMF could be persuaded to embrace or at least accept progressive or radical policies that would directly help solve the current economic crisis, distribute the costs much more equitably among the population, and appear fair and reasonable to many Sri Lankans. The gleam in my eye is a nationally-defined economic policy programme that effectively addresses the fiscal crisis, is and is seen to be equitable, and has significant popular support. The greater that political support, the greater the bargaining leverage the government will have over the IMF.

This aspiration is optimistic but realistic. How do we achieve it? We need to start by dropping any notion of the IMF as some all powerful bogeyman working hand in glove with international capital to squeeze the poor of the world. If the IMF were that powerful, it would be able to enforce the agreements that it signs with governments. In reality, a large proportion fail, almost all because national governments don’t uphold their end of the bargain. The IMF is powerful but it is ultimately just another international organisation struggling to for continued existence and funding amid competing political pressures, notably between the governments that provide it capital and those that borrow, and between the West, China and Russia. The IMF suffers one systemic weakness in relation to its borrowers. Its loans are made in more or less emergency situations. They typically involve large up-front capital injections. Once governments have that upfront money, their incentives to honour all the promises they made about revenue, spending and reform are blunted.

The IMF itself has changed considerably since the latter part of the last century and the first decade of this when what appeared to be standard policy packages gave birth to the narrative about its merciless and unyielding insistence on public spending cuts in all circumstances. Over the past decade or more it has, through its research and publications and the speeches of its leading figures, become one of the most influential global advocates of greater income and gender equality in the interests of economic growth, and more effective social protection for the poorest, through direct public action. It is probably relevant that the managing director post has been held by a woman since 2011 (Christine Lagarde and now Kristalina Georgieva) and the first female Chief Economist was appointed in 2019 (Gita Gopinath).

We do not yet know the details of the agreement that the government is likely to sign with the IMF. But we do know the outlines. The package does not conform at all to the narrative of savage public spending cuts. There will be spending cuts, although the current government has already sensibly pre-empted some of them by dialling back on the massive infrastructure projects that formed the centrepiece of the economic policy of the Rajapaksa governments. There are clearly also hints from Washington about the scope for saving public money by cutting back on the excessively large armed forces and defence budgets. What is not to like about that? Otherwise, the IMF simply does not see much scope for cutting public spending without causing economic, social or political damage.

The most interesting parts of the draft agreement are more constructive. The IMF has positively encouraged the government to establish a serious cash transfer programme to protect the poorest Sri Lankans during the current crisis. The government has formally made preparatory moves, but in a very unconvincing way (see below). The IMF also emphasises increasing government revenue, which is essential for long term economic stability, and privatising those state owned enterprises that cause government large recurrent financial losses. Both are of course controversial: revenue because of the way the government has appeared to load all the burden on personal income taxpayers; and privatisation partly on principle and partly because previous privatisations directed by the current President had more than a whiff of scandal around them. We also know that the IMF is at least contemplating introducing into the agreement broad governance conditions that would probably be popular if they were not tainted by implications of violated national sovereignty.

On balance, the IMF has a more progressive attitude to the policies needed to tackle the current crisis than does the current government. There is scope for a government to take advantage of this situation by committing, in deeds as well as words, to an economic adjustment programme that would be more effective and visibly much more equitable. If communicated well, such a programme could become relatively popular. The more popular it is, the stronger the bargaining position of the government in relation to the IMF. The IMF might be willing to tolerate or even embrace an even more progressive stance. What might that more progressive nationally designed programme look like? Here are three important potential components.

A real safety net for the poorest

In mid 2022, in the early stages of the IMF negotiations, the government announced that it would fold the existing Samurdhi scheme into a much larger programme to transfer Rs7,500 monthly to the most vulnerable households. This was anyway long overdue. The Samurdhi scheme has for many years been shamefully inadequate for a country that had attained the formal status of a middle income country before losing it again in 2022 because of collapsing income levels. Samurdhi has been well researched and found to be woefully inadequate even before the pandemic and the economic crisis. It covers just 27% of households in Sri Lanka and systematically excludes over 58% of eligible recipients. The administrative costs are high because it is also, and perhaps primarily, an employment programme for Samurdhi officers. Many recipients are not formally eligible. In July 2022, Verite Research published a paper that showed in detail that there is a very high overlap between household incomes and the amount of electricity used. It would be possible to bypass Samurdhi and quickly establish basic eligibility for an effective cash transfer programme by using records of electricity use. These are available for 99% of households. The government did no such thing. It instead announced that it was undertaking a national household survey to determine eligibility for the new cash transfer programme. Nothing was said publicly about the criteria that would be used to determine eligibility or how this process would avoid the high levels of politicisation and personalism that have undermined Samurdhi. The survey seems to have taken much longer than expected. In January of this year it was announced that the survey was still ongoing; the cabinet agreed that the new welfare payments will begin in May. At the same time, it was announced that the government would, for a period of two months, give 10 kg of rice per month to two million low income families, including Samurdhi beneficiaries. Given the logistical challenges of distributing rice in this way and the learning costs involved, it seems idiosyncratic to create such a programme just for a two months period. Perhaps the government does not seriously intend to establish an effective safety net for the poor but rather to delay, confuse and prevent the political opposition from mobilising around this issue? The World Bank’s Colombo office has for many years been urging the government to establish a proper safety net for the poor. It would likely join the IMF in celebrating real steps in this direction.

Sharing the tax burden: cancel exemptions

Sri Lanka needs more public revenue. As a proportion of GDP, the government currently collects less than half of what it collected in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, and less than half what one would expect of a country at this income level. The most urgent need is to assure any future lenders, public or private, that the government would be able to repay any loans it receives, including concessional loans. The more important need is to fund, long term, the public facilities and services that Sri Lankans so badly lack, starting with education and a reasonable social safety net for the poorest, including the growing number of elderly on very low incomes. But the government has increased tax resistance by increasing personal income tax in a provocative way. What might a different government do? There is actually a major potential source of increased tax revenue that could be quickly tapped without the complex and time consuming organisational and legal procedures that would be needed to set up a recurrent wealth tax. Sri Lankan companies have for decades benefitted from extremely generous tax exemptions of all kinds. The exemption system has been examined many times. The conclusions do not change much. There are too many tax exemptions for investors; they are typically justified in terms of attracting foreign investment but have failed miserably to achieve that objective. Exemptions are given mainly through direct, personal lobbying and the use of ministerial discretion. There is no good recordanywhere of what exemptions have been given, their dates of expiry or the conditions attached to them. The IMF – along with the World Bank, the UN and the OECD – has long called for a cut back in exemptions for investors, globally as well as for Sri Lanka. Now is a good time for the government to respond by simply cancelling all tax exemptions for investors and applying a single VAT rate and a single corporate income tax rate to all companies. Because there are currently so many exemptions and so many companies at present pay little or no income tax, the new standard corporate income tax rate can be lower than the current highest rate of 40% but higher than the lowest rate of 10%. Will the private sector be upset? Most companies will, although some stand to benefit. The objectors need to be reminded just how much lobbying has gone into establishing the current exemptions. Potential future foreign investors will mostly prefer a simple and uniform corporate tax regime to one riddled with political influence. Would this not be a violation of contracts on the part of government? In some cases, yes. But the government has just violated a lot of contracts by not repaying foreign creditors. Cancelling tax exemptions, on grounds of national economic necessity and more equal sharing of the costs of the crisis, is surely no more reprehensible than failing to repay debts?

Sharing the tax burden: tax real estate

Sri Lanka levies no wealth taxes. Large sections of the population have become much wealthier over the past half century. One of the most visible signs of this wealth is the boom in residential and commercial construction, above all in Colombo and the surrounding areas of the Western Province. Real estate taxes, whether in the form of annual charges on owners or occupants of residential and commercial property (rates as they are termed in Sri Lanka) or taxes on real estate sales or ownership transfers (stamp duty), are generally the most efficient and effective of taxes. In Sri Lanka they are negligible. In 2009, the latest year for which data are easily available, they accounted for just 0.08% of GDP. By contrast, land values in Colombo are now very high. Significant revenues could be raised, relatively quickly, by establishing a new real estate tax system. Technology is strongly supportive. It is now possible, using various combinations of aerial surveillance (satellites, drones) and street level digital and eyeball observations to identify all significant urban properties that seem eligible for a recurrent property tax and to estimate their taxable values. Significant revenues could be raised within two years and a major start would thereby be made in taxing wealth.

The only thing needed now is a government committed to fleshing out the kind of radical but sensible and fair programme outlined here. That programme would of course generate opposition but not from Washington.

24.02.2023

Courtesy Groundviews