|

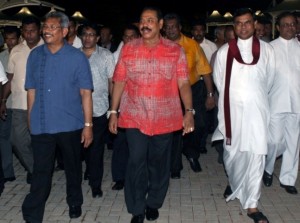

| Basil R: on right gets the Divinaguma dept |

Charitha Ratwatte

The Government has gazetted a Bill, on 27 July 2012, to set up a Divi Neguma Department, which will take over the existing Samurdhi Authority, the Southern Development Authority and the Udarata Development Authority (successor to the Kandyan Peasantry Commission).

The Bill will also set up a Divi Neguma Community Based Organisation, Divi Neguma Community Based Banks and Banking Societies.

It is significant that what is being established is a run-of-the-mill Government department which will have to comply with the full force of the Financial Regulations (FR), Administrative Regulations (AR) and the Establishment Code (Esta Code).

Development workers have long complained that this regulatory framework ties up the public service in an environment in which development work is hindered by red tape.

Further, the Department of Divi Neguma will come under the purview not only of the Auditor General, Government of Sri Lanka, but also of the Public Accounts Committee of Parliament. Statutory authorities, such as Samurdhi, Udarata Development and Southern Development, which do not have to comply with the AR, FR and the Esta Code have been specifically set up to avoid these claimed constraints.

Setting up a mere department of government does not need special legislation, but in the case of Divi Neguma, the repeal of the Samurdhi, Southern Development and Uda Rata Development statutes are a part and parcel of the bill.

Not a new thing

The setting up of community based organisations to spur on people’s development programs is not a new thing in this country. The Rural Development Societies in the time of first Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake was the first.

Subsequently community centers, young farmer’s clubs, cooperatives, youth clubs, women’s societies, cultivation committees, fishermen’s associations, sports clubs, gramodaya mandalayas, Samurdhi banku sangam, Gemidiriya village organisations, etc. were set up under a variety of Government-sponsored programs.

In addition to this, genuine people’s organisations such as the ubiquitous Death Aid Societies (Marana Adhara Samithi), religious organisations such as Dayaka Sabhas organised around Buddhist places of worship and similar associations for other religious groups also came into being. Sarvodaya and Sewa Lanka branches, YMCA, YMBA, YMHA and YMMAs are other examples. Business groups also got together under the banner of ‘Velanada Sangamayas’ and Chambers of Commerce, etc.

For the health sector, the Red Cross, St. John’s Ambulance and Saukyadana were active; conflict and human rights violations brought into being organisations to protect human rights at the community level. The State also supported these community organisations from time to time; the Janasaviya Trust Fund (JTF) was specifically set up to partner with community-based organisations in small-scale rural construction, mother and child nutrition, micro finance and social mobilisation initiatives.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), through its Isuru program, and the JTF, through its micro credit window, brought into being a large number of Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs). The State has recognised the capacity of these MFI by gazetting draft legislation to bring these institutions under the prudential regulation of the Monetary Board of the CBSL.

KPC report

The case for the need for a specifically targeted community based development program was succinctly stated in the 1951 Sessional Paper XVIII ‘Report of the Kandyan Peasantry Commission’ (KPC). The Commission was chaired by N.E. Weerasooria; the other members were T.B. Panabokke Jnr., H.R.U. Premachandra and Cyril E. Attygalle.

The commission’s terms of reference involved a wide field of inquiry. Its purpose was to obtain an overall picture of the social and economic life of the Kandyan peasantry in the Central Province and in the Province of Uva and to ascertain the measures that should be adopted to ameliorate their condition. The teport quoted from the Soulbury Report of 1945 (paragraph 182) to summarise the problem of the Kandyan peasantry, which it said would be especially applicable to the wet zone of the island:

‘We cannot doubt from the evidence before us that, especially in the latter half of the 19th century, the establishment of the plantations reacted unfavourable on the Kandyan land owners. By various means which, to say the least, were prejudicial to the latter, land was acquired to form large estates, first for planting coffee, and later tea and rubber. The inevitable backwardness of a hill country population as compared with its maritime neighbours was accentuated by the spread of educational, health, agricultural and economic facilities through the relatively thickly populated and accessible low country much earlier and on a far larger scale than was possible in the interior. The result is that today the Kandyan peasantry labour under serious social and economic disabilities as compared with their more fortunate fellow agriculturists of the low country.’

On the needs of the village communities of the dry zones of the island, the KPC quoted from the Donoughmore Report of 1928: ‘…we would here wish to recommend that special consideration should be paid to the needs of the villages in the dry zones of the Island. Measures are urgently needed to break the vicious circle in which villagers of these parts live. Exposure to malaria and ankylostomiasis has sapped much of their vitality and has left them without energy and even the will to perform the hard work essential to successful cultivation; their failure to undertake this work results in poor crops and therefore in shortage of food; and shortage of food undermines their physique and renders them ready victims to the ravages of disease. Even if, in a good season, their crops be plentiful, they are forced to make over the greater portion either absolutely or at nominal prices to shopkeepers and others whom their extreme poverty has forced them in bad seasons to look for assistance.’

Inequity

The KPC Report shook the conscience of the nation and the Kandyan Peasantry Commission was set up as a Government department with its head office located in Kandy to undertake a rapid development of the Kandyan Provinces. However, the inequities in resource allocation and development, which were highlighted by the Donoughmore and Soulbury Reports and recited in the KPC Report, existed for many years thereafter without any significant change.

Free education and health care, relocation of population from the congested south west quarter of the island to the former Eastern and North Central Provinces, with the connected infrastructure development, made some improvements. However, the fundamental economic and social advantage the south west quarter of the island had due to the entre-port trade due to the import-export hubs of Galle and later Colombo ports, persists up to today. Indeed, it has been argued that the decline of the south took place after the main port was shifted to Colombo from Galle.

The opening up of the plantations created a development cocoon in and around the estates and their work force, but made no impact on the Kandyan peasants who were deprived of their lands by the rapacious Waste Lands Ordinance (1897), by which lands for which there were no title deeds were deemed to be owned by the Colonial Government and parcelled out to British planters and British Government servants at bargain prices.

Other than the colonisation schemes and the Gal Oya project it was only after the Integrated Rural Development Programs (IRDPs) targeting specific districts such as Kurunegala and Hambantota in the early days and expanding to other districts later, that areas outside the south western quarter received an injection of targeted development.

Indeed, if one takes a map of Sri Lanka and superimposes the various development initiatives, up to the time of the IRDPs, one would find extensive education, road, healthcare, communication, and other infrastructure in the south west quarter, around the plantation areas, and the Jaffna peninsula, up to the time of the land settlement schemes in the North Central and Eastern Provinces.

The Paranthan Chemical Corporation in the North, Cement Factory at Kankesanthurai and the Paper factory at Valaichchenai were the only large isolated investments outside the south west quarter of the island. The Kandyan areas were the beneficiaries of some infrastructure, health and education facilities under the KPC.

Other than these isolated investments, the inequity in the allocation of development resources between the populous south west quarter of the island and the rest of the country can be seen to be reflected in the regional representation of the youth unrest which terrorised the Sinhala areas in 1971, 1989 and the north and east after 1986.

Solving the issues

Can the Divi Neguma Department and the various institutions set up under the agency solve these issues of inequitable allocation of resources? Though overall there has been an improvement in the quality of life of the large percentage of the population, huge inequities remain. Otherwise how can be justify the fact that although we are classified as an ‘emerging lower middle income country,’ still a figure as large as 35% of the population are beneficiaries of Samurdhi handouts?

Free education, free healthcare, free water for farmers, and subsidised transport are fast becoming unaffordable. Healthcare without the recovery of costs was designed at a time when the population was relatively young and expanding, at a time when the major health issues were communicable diseases such as malaria, filaria and bowel disease.

Further the health service delivery infrastructure and net work was also designed to cope with these issues of the past. Today we are a rapidly ageing population (the March 2012 Census gave the population growth rate as 0.7%, way below the 2.1% required for the current population to replace itself) and the rampant illnesses are lifetime ones and illnesses of longevity, such as blood pressure, cancers, kidney disease, diabetes, lung disease, and financial allocations for healthcare, are simply not adequate to cope.

So called free education coexists alongside the ubiquitous private tuition industry and so-called international schools! The result is the crippling shortage of drugs and services in Government hospitals, an ongoing crisis in education, Z scores, universities, etc., among others things, high and unsustainable budget deficits. It is reported that for this year the budget deficit is targeted to reach 8% of GDP, way above the planned 6.2%.

Culture of dependency

Given this scenario, the ability of another Government department, however dynamically led, in attempting to overcome the historical inequities of development which have bedevilled this country since the 1900s is, to put it mildly, doubtful. The danger is that the Divi Neguma Department might, on the other hand, institutionalise the ‘culture of dependency’ we are trapped in.

Samurdhi has become an artificial crutch, which is very badly targeted. Many undeserving people, whose incomes and assets are way above the so-called poverty line receive Samurdhi benefits, while many other who are deserving according to the criteria do not benefit from the programme. Report after report has commented upon the need for improved targeting.

No one ever graduates from Samurdhi. It has in effect bred a culture of permanent dependency. It is doubtful whether, just another atrophied Government department, hamstrung by ARs, FRs and the Esta Code, staffed by demotivated, stick to the rule book, careerist officers, working in the totally politicised and constraining environment of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, dreaming of a peaceful retirement, after a long ‘no decision, no trouble’ career, living in abject fear of audit queries and of having to be pilloried before inquisitorial proceeding at the Public Accounts Committee, will not be able to make much of a difference.

Social welfare programs in Sri Lanka need reform urgently. Targeting is bad, delivery costs too high, the almost universal coverage of benefit is unaffordable, the programs have to be much more flexible and innovative, interventions must be modernised and disbursement must be of effective amounts, not rates fixed eons ago, eaten away by inflation.

Informal workers have to be caught up in the welfare net, identification has to be firmed up, micro insurance facilities must be introduced, communication and information technology must be fully utilised for disbursement, especially the potential of mobile phone technology, such as Dialog’s Ez Cash.

Whether the Department of Divi Neguma, working under the traditional bureaucratic limitations and constraints, will have the capacity to make these epochal reforms is doubtful. The ‘crutch economy’ we are trapped in will continue.

Divi Neguma legislation

There are other controversial issues arising from the proposed Divi Neguma legislation. For example, one of the objectives specified in the draft legislation is ‘promoting a micro enterprise banking system’.

The objects of the Divi Neguma Department as provided by Article 4(e) are: To provide micro financial facilities for the purpose of promoting the livelihood development of people’. Among the powers of the Department, provided by Article 5 (f) is to ‘supervise, manage, monitor and audit Divi Neguma …community based banks and Divi Neguma community based banking societies.’

Article 7 (b) provides that the Divi Neguma National Council will consist of among others the: ‘Director of the Department who is in charge of the subject of Micro-Finance’. Among the objects of the Divi Neguma community based organisations are: Article 10 (e) ‘to provide opportunities as may be required to improve the savings habits of Divi Neguma beneficiaries’ and Article (f): ‘to expand financial facilities and to improve the investment capabilities’.

Among the powers of the Divi Neguma community based organisations are: Article 11(d) ‘to provide necessary facilities for Divi Neguma beneficiaries to secure loans from Divi Neguma community based banks’ and Article 11(g) ‘to collect and manage… savings of Divi Neguma beneficiaries’.

Article 13 provides that ‘the funds of the Divi Neguma community-based organisations shall be deposited and maintained in a Divi Neguma community based bank…’ Part VI of the Bill deals with Divi Neguma Community Base Banks and Part VII ‘Divi Neguma Community Based Banking Societies’.

Article 31 gives the ‘the Divi Neguma community-based banking societies the power to accept deposits from Divi Neguma community-based banks’. Article 34 provides that the ‘provisions of the Banking Act and the Finance Business Act shall not apply in respect of banks and banking societies’.

Controls and exemptions

These provisions create institutions providing financial services, including banks, which are completely outside the prudential regulation of the Monetary Board of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Further the Finance Business Act controls and regulates the authority of financial institutions taking deposits from the public. The Divi Neguma is exempt from this control too.

Further the Bill in its interpretation section provides a definition of micro finance as: ‘mean a type of banking service that is provided to employed or low income individuals or groups who would otherwise have no other means of gaining financial services’.

This is in sharp contrast to the definition of micro finance in the recent Microfinance Bill gazetted by the Government, which by Article 33 defines ‘microfinance business’ as: ‘(a) financial accommodation in any form; (b) other financial services; or(c) financial accommodation in any form and other financial services, mainly to low income persons and micro enterprises in conformity with the Schedule to the Bill’.

The Schedule contains one dozen types of financial services covering the whole gamut of business activity. Further in terms of the Microfinance Bill, only companies, voluntary social service organisations and societies registered under the relevant law are entitled to a license. The Divi Neguma Department will not be entitled to a license.

Further the Microfinance Bill empowers the Monetary Board, by Article 25 to ‘set principles and standards’ to ensure that microfinance is carried out in a ‘transparent, professional and prudent manner,’ in respect of entities being regulated by the Samurdhi Authority, the Commissioner of Agrarian Development and the Commissioner of Cooperative Development and the Registrar of Cooperatives. The microfinance industry is a dynamic player in our financial services sector with over 16,400 MFIs in operation.

Complete confusion

Here we have a classic Ripley’s ‘Believe or Not’ scenario – two bills dealing with microfinance, giving completely different definitions of what microfinance is! The Monetary Board has the power to give directions to the Samurdhi Authority in terms of the Microfinance Bill. But the Divi Neguma Department, which is to be the successor to Samurdhi, is exempt from the Banking Act and the Financial Services Act only, not from the Microfinance Bill, when it is enacted.

But in terms of the Microfinance Bill, Divi Neguma is not entitled to a license to conduct microfinance activities, however defined, since Divi Neguma is a Government department! Logically it can be argued that since the Divi Neguma Department is the successor to the Samurdhi Authority, the Monetary Board of the Central Bank should be able to set standards and principles for the Divi Neguma departments, banks and Banku Sangam. But banks should come under a much higher level of prudential regulation; the Divi Neguma Banks are unique in being exempt from the Banking Act.

This is utter and complete confusion! There will, without doubt, be chaos in the delivery of financial services to the poor if both these bills are enacted as they are presently drafted.

The prudential regulation of the Monetary Board of the Central Bank, however competent, is essential, for the public good, for any organisation providing financial services and taking deposits from the public. We have seen the chaos caused by the Sakvithis, Danduwam Mudalalis and the Golden Keys due to lack of or lax prudential financial regulation. As the draft legislation on Divi Neguma presently stands, this is lacking and that is why Divi Neguma may end up being one huge ‘white elephant’.

The Oxford Advanced Learners’ Dictionary defines a ‘white elephant’ as ‘a thing that is useless and no longer needed, although it may cost a lot of money’. The origin is from the story that in Siam (today’s Thailand) the king would give a white elephant as a present to somebody he did not like. That person would have to spend all his money on looking after the rare animal.

courtesy: Financial Times/DBS