Sri Lanka’s unilateral withdrawal from Resolution 30/1 is a clear rejection of human rights and accountability and displays total disregard for UN Member States

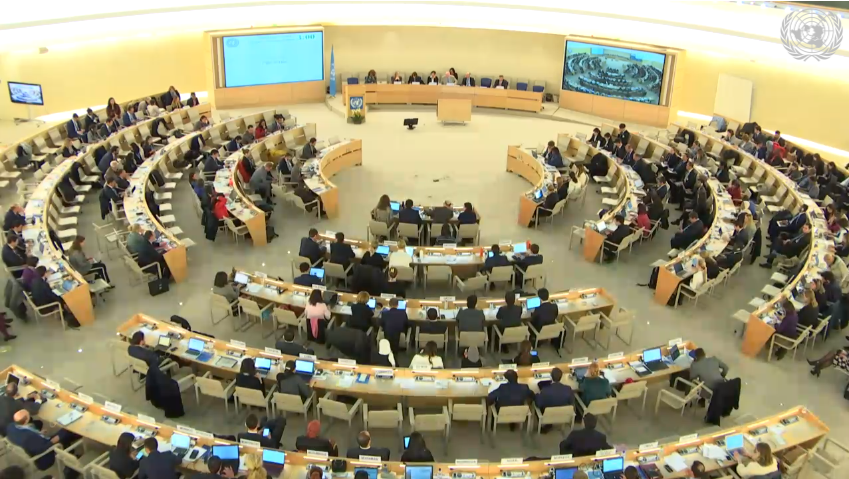

Sri Lanka is unwilling & unable to hold state officials accountable for heinous violations of int’l human rights & humanitarian laws. Reason-it is the state itself that committed these heinous crimes”— V. Rudrakumaran.NEW YORK, USA, February 24, 2020 /EINPresswire.com/ — Ahead of the opening of the 43 rd Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council on Monday, the Transnational Government of Tamil Eelam (TGTE) calls on the international community to abandon any attempt to resuscitate the defunct transitional justice initiative on Sri Lanka detailed in UNHRC Resolution 30/1, “Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka,” and instead adopt a remedial justice agenda that includes referring Sri Lanka to the International Criminal Court (ICC) and referral of Sri Lanka to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) under the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of Crime of Genocide by a State Party to the Convention.

“Four years of Sri Lanka deliberately failing to fulfill its transitional justice obligations under Resolution 30/1 should have been enough reason for the Council to change its course on Sri Lanka at its session last year and adopt a remedial justice agenda, as TGTE called for,” said TGTE Prime Minister Visvanathan Rudrakumaran. “Instead, the Council opted to roll over the resolution, resulting in the further entrenchment of Sri Lanka’s culture of impunity and the return to power of those most responsible for the crimes perpetrated against Tamils during the armed conflict. Ultimately, the UNHRC’s attachment to transitional justice moved Sri Lanka away from accountability and justice, not toward it.

Sri Lanka’s unilateral withdrawal from Resolution 30/1 is a clear rejection of human rights and accountability and displays total disregard for fellow UN Member States. Thus, there is no point at this juncture to discuss transitional justice. Rather,remedial justice is the call of the hour.”

According to the 2012 U.N. Internal Review Report (Petrie Report) on Sri Lanka, there are credible reports that during the final months of war, when President Gotabaya Rajapaksa served as Sri Lanka’s Defense Secretary, the Sri Lankan army killed 70,000 Tamil civilians. In 2016, the U.N. Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances reported that Sri Lanka had the second highest number of disappeared cases before them. When including the thousands of Tamils disappeared, the Tamil death toll jumps to more than 100,000 as the war ended.

Resolution 30/1, co-sponsored by Sri Lanka and unanimously passed by the Council in 2015, commit Sri Lanka to establishing a judicial mechanism involving foreign judges and lawyers to hold perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity and other international crimes committed during Sri Lanka’s 26-year armed conflict accountable and to creating a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, among other transitional justice measures.

“When the Rajapaksas lost the 2015 election and the Sirisena government obtained power, the international community viewed the regime change as an opportunity to achieve transitional justice. However, the last five years have shown that perception was not the case. Rather, the Sirisena government used transitional justice as a sophisticated form of impunity,” Rudrakumaran said.

“The establishment of the Office of Missing Persons in the face of the declaration by former Prime Minister Wickremesinghe that most of the disappeared are dead is an illustration how the Sri Lankan state used transitional justice to deceive the UNHRC and the greater international community,” Rudrakumaran said.

This deception is further underscored by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michele Bachelet’s statement in her most recent report on Sri Lanka released earlier this week, that, since 2015, “very little action has been taken to remove individuals responsible for past violations, to dismantle structures and practices that have facilitated torture, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, and to prevent their recurrence.” In other words, despite ongoing UNHRC oversight of the resolution’s implementation, the UNHRC’s transitional justice initiative failed.

Commissioner Bachelet also notes in her report that “there has been minimal progress in the investigation and prosecution before Sri Lanka’s courts of the long-term emblematic cases highlighted in previous reports of the High Commissioner to the Human Rights Council…the absence of progress on these cases highlights the systemic impediments to accountability in the criminal justice system.” In other words, Sri Lanka is both unwilling and unable to hold state officials to accountable for heinous violations of international human rights and international humanitarian laws. The primary reason for it, it is the state itself that committed these heinous crimes. This exact combination of lack of will and ability is what remedial justice broadly speaking and the International Criminal Court (ICC) in particular, were designed to address and overcome.

“History has repeatedly shown us that when the state itself is the perpetrator of grave crimes and the architect and overlords of widespread institutional discrimination and bias against the group that the victims and survivors belong to, which in the case of Sri Lanka is the Tamil people, there is no way for victims to obtain justice so long as the state is involved in the accountability and institutional reform processes,” Rudrakumaran said.

“Given the fact the person who was the architect of this mass atrocity, which attempted to destroy the very existence of Tamils as apeople, is now Sri Lanka’s President,the only forum that can pierce head of state immunity and bring President Rajapaksa to justice is the International Criminal Court (ICC).The ICC is also

the only international forum that currently exists where other high-ranking Sri Lankan government and military officials most responsible for the Tamil Genocide can be prosecuted.

Thus, TGTE calls on the UN to refer Sri Lanka to the ICC.” Continuing impunity is a threat to security as the High Commissioner stated in her most recent report, that the government’s failure to “deal comprehensively with the past, risking to repeat cycle of violence and human rights violations”. The violence against the Muslims last year is a demonstration of the above.

Steven Ratner, one of the members of the three-person Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, which advised Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on human rights violations related to the end of the Sri Lankan civil war, has written in the American Journal of International Law,; The Sri Lanka case also demonstrates, however, three clear obstacles on the bridge between law and behavior. First, much of the law regarding accountability for human rights atrocities has developed in situations where governments are judging their predecessors–true cases of transitional justice…For nontransitional situations, the obstacles to accountability are profoundly increased, for the leaders have much more at stake: full investigation could lead to freezing of assets, public humiliation, and even a trial before a national, foreign, or international court…the limiting principle [of transitional justice] still seems to be that governmental officials do not like to investigate themselves. Those states may be willing to investigate the violations of the losing side—as Sri Lanka is with regard to LTTE crimes—but such investigations then appear to be no

more than victors justice.

“A prerequisite for transitional justice is acknowledgment of the violations committed by the party concerned. However, in Sri Lanka, thus far, there has been no acknowledgment of the violations. Rather, we have repeatedly witnessed denial and triumphalism,” Rudrakumaran said.

In an interview with the BBC in 2010, when President Rajapaksa was still Defense Secretary, he told the reporter that there is “not a single case” of the Sri Lankan army committing war crimes. In a 2012 BBC interview, when asked about state forces disappearing people, Gotabaya denied the accusation and responded, “I am the secretary of defense, I have investigated this. You don’t take the word from these people, take the word from me.’ This stands in total contradiction to his recent claim the “all the missing are dead.”

We note with regret that the High Commissioner downplayed the Sri Lankan assertion that missing are in fact dead and that he can’t bring back the dead. The UNHRC and other international bodies can and should demand that President Rajapaksa reconcile his competing claims and hand over all information he obtained to Sri Lanka’s Right to Information Commission, established under the Sri Lanka’s Right to Information Act, as well as to the UN, in accordance with the international principles the Right to Know and the Right to Truth.

“The return of the Rajapaksas to power last year and the actions of the government since then demonstrate that Tamils can never enjoy equality or dignity in Sri Lanka. The fact that Rajapaksa won with Sinhala votes shows that Sri Lanka is a rigid ethnocratic Sinhala Buddhist state with no room for justice for Tamils.

The President’s statement that he will not engage in any political resolution without the support of Sinhala majority underscores this. It is nothing but a tyranny of the majority camouflaged as democracy. In addition, the Government’s prohibition of the national anthem being sung in Tamil during the official Independence Day celebrations on February 4, 2020, was a hostile act against Tamils and a telling sign of the state’s disinterest in reconciliation. “Justice and reconciliation are the twin pillars of transitional justice. Clearly, there is no room for transitional justice in Sri Lanka,” Rudrakumaran states.

Instead, as High Commissioner Bachelet notes in her recent report, “The Government appears to prioritize development to deal with the past. The 2030 Agenda includes SDG 16 to ‘promote peaceful and inclusive societies, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. A commitment to human rights, justice, accountability and transparency – all of which are recognized as prerequisites for an enabling environment in which people are able to live freely, securely and prosperously – underpins the 2030 Agenda.”

“The first objective of the Human Rights Council listed in Resolution 5/1 is ‘the improvement of the human rights situation on the ground.’ Instead, what we have seen in Sri Lanka since the adoption of resolution 30/1 is further degradation of human rights. This is not surprising. As transitional justice scholar Makau W. Mutua said in the context of Rwanda, ‘transitional justice serves to deflect responsibility to assuage the conscience of states which were unwilling to stop the genocide.’ It does not serve victims and survivors,” Rudrakumaran pointed out.

“It is therefore incumbent upon the Council, in order to fulfill its duty, to move on from transitional

justice and pursue a different, viable approach to holding Sri Lankan perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide accountable: remedial justice.

TGTE believes that remedial justice can accomplish what transitional justice never could and never did.”

ABOUT THE TRANSNATIONAL GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL EELAM (TGTE):

The Transnational Government of Tamil Eelam (TGTE) is a democratically elected Government of over a million strong Tamils (from the island of Sri Lanka) living in several countries around the world.

TGTE was formed after the mass killing of Tamils by the Sri Lankan Government in 2009.

TGTE thrice held internationally supervised elections among Tamils around the world to elect 132 Members of Parliament. It has two chambers of Parliament: The House of Representatives and the Senate and also a Cabinet.

TGTE is leading a campaign to realize the political aspirations of Tamils through peaceful, democratic, and diplomatic means and its Constitution mandates that it should realize its political objectives only through peaceful means. It’s based on the principles of nationhood, homeland and self-determination.

TGTE seeks that the international community hold the perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide against the Tamil people to account. TGTE calls for a referendum to decide the political future of Tamils.

The Prime Minister of TGTE is Mr. Visuvanathan Rudrakumaran, a New York based lawyer.