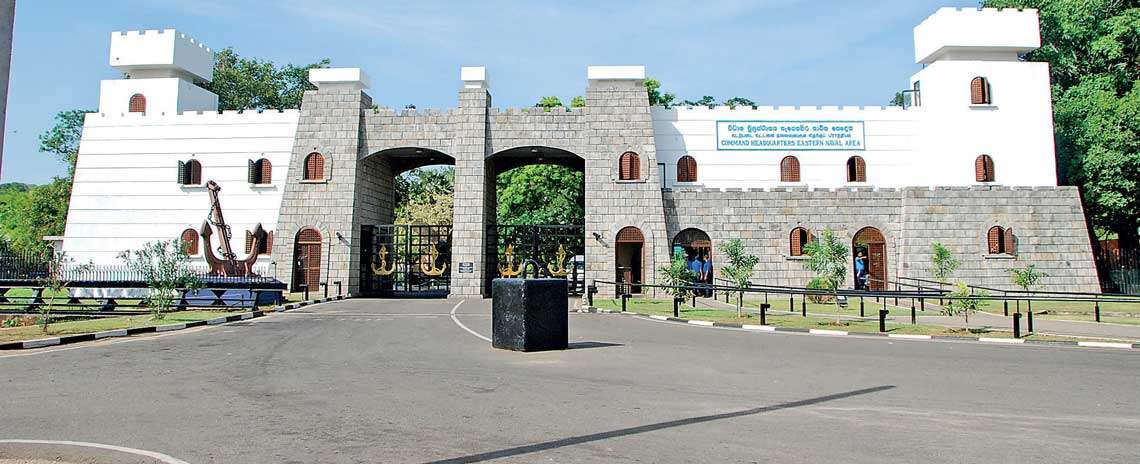

Image: Navy base, Trincomalee.

The progress of ongoing criminal investigations into the grisly killing of several Tamil youths following a racket of abduction for ransom, spearheaded ‘allegedly’ (here, I use the term quite deliberately) by a Naval officer and others during 2008-2009 will be the crucible on which this Government and this Presidency’s commitment to promises made, will be tested most severely.

Fair differences between then and now

Unlike other instances of the killing of youths, such as what occurred in Trincomalee in 2006, ready excuses cannot be offered as to the chain of evidence becoming cold or pointing to key witnesses living overseas being reluctant to return to testify, as would be naturally the case given the trauma that they have had to undergo.

It must be fairly acknowledged that one distinguishing feature of the current ‘yahapalanaya’ administration is that the Navy suspect was arrested and produced before court which would have been out of the question if the Rajapaksas were still in power. Then again, the fact that the Court inquiring into the matter had proceeded to act according to law is also another demonstrable difference when compared to the past. These officers of the state must be commended to the highest extent possible for carrying out their functions with due diligence despite the enormous and impossible strains put on them by political forces.

However and despite these undoubtedly positive developments, the key question here is whether the chain of impunity at the highest levels will be broken and those responsible for enabling these acts to take place and persistently protecting the perpetrators will be held accountable to law. For ultimately, systemic impunity is the core issue, not really the arrest, questioning or even punishment of minions who will doubtless be replaced by other minions in the correct political circumstances, perpetuating these crimes from which we have suffered as a nation for decades. Indeed, the arrogance with which the suspect in this ongoing case smiled and strutted while in handcuffs testifies to this web of impunity.

Central issue of tackling the chain of command

Sri Lanka is no stranger to the killing of children. The periodic uncovering of graves with the skeletal remains of massacred children decades ago or nearer in time, is just one manifestation. From the killing of child monks in Aranthalawa in 1987 by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam to the children caught up in reprisal attacks by armed forces stationed in the North and East at the height of the conflict and including the vast numbers of children killed in the South during the second insurrection of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, this earth should weep blood for the countless innocents mowed down in the course of grievous sins committed by ambitious men.

This week marks the International Day of Disappearances as the month comes to an end. These are reflections that are therefore opportune in this context. ‘Disappearances’ and extra-judicial killings mark the lowest ebb of a nation’s functioning. As long as these crimes remain unpunished, from the highest levels of those who ‘protected’ or enabled such atrocities whether in the military chain of command or in the state prosecutor’s office to those carrying out the acts, only nonsense can be spoken of reconciliation. Put simply, families of those who have had their members disappeared or killed, will not be satisfied by money payments handed out to them or by a state official blandly informing them that a crime has occurred. This, they already know. What they seek is formal state acknowledgement of these acts at the minimum and as a necessary corollary, the chain of impunity to be broken.

Our constitutional jurisprudence has consistently stressed the principle that superior officers exercising responsibility over subordinates who commit rights violations, will themselves be held responsible. There are, of course, some notable and puzzling exceptions to this rule as was evidenced in the Embilipitiya Case where the commanding officer of the camp where Sinhalese school children had been detained and ‘disappeared’ during the eighties in the deep South, due to a personal vendetta of individuals was not held liable in law.

In the Supreme Court, he was given the right to be promoted to the rank of Major General on the basis that he had been acquitted in the criminal courts on the basis that he could not directly be responsible for the enforced disappearance of the children at the army camp. The lenient position taken by the Supreme Court at the time belied constitutional considerations and the protection of rights Parents of the victims had, in fact, testified that they had brought their appeals to this commanding officer in order to find out what had happened to their children but that he had done nothing.

The law must take its course

Certainly these were not precedents that afforded reassurance that the Rule of Law was being upheld with fear and favour to none. Writing for the International Commission of Jurists in 2010, I pointed to the fact that the refusal on the part of Sri Lanka’s highest court even when the Bench was otherwise proactively responding to violations of fundamental rights, was a major failing (Still Seeking Justice, ICJ).

But despite some aberrant decisions in the exercise of its constitutional jurisdiction, the Court has upheld the principle is that a superior officer protecting a subordinate who engages in atrocities or ‘acquiescing’ in that act, will be held responsible. As a matter of law therefore and applying these principles to the ongoing case of the Navy abductions, those who chirrup airily that officers implicated at the highest levels of Sri Lanka’s military hierarchy ‘only’ helped the suspect, must acquaint themselves with the fact that this, as assessed by authoritative local precedents and notably under international law, cannot absolve the individual of legal responsibility, under the criminal law and certainly in terms of constitutional protections.

What remains is for the law to take its course. Political interference in that process will only be the last nail in the ‘yahapalanaya’ coffin. That much must be categorically said. These killings of children were at the heart of a ransom racket and had pure and common greed behind them. They speak to a particular horror that stands in a category all of its own.

It is a nightmarish and devilish blemish on this nation’s memory and must be exorcised with maximum force.

- Sunday Times