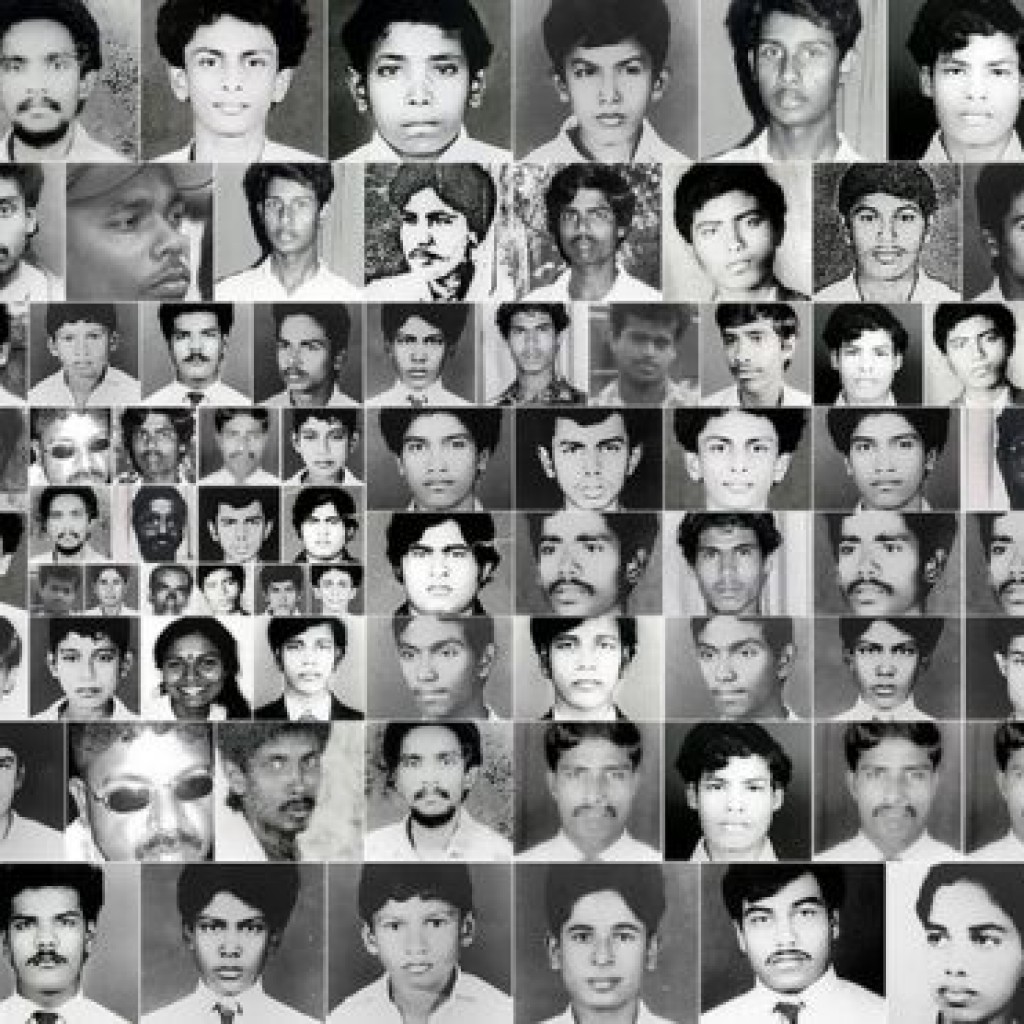

(Image: Amnesty International)

Hon Minister Samaraweera.

OMP – follow-up to submission dated 1 May 2016, meeting at Foreign Ministry on 9 May 2016, and leaflet of 13 May 2016

- We are writing as a follow-up to our Memorandum dated 1 May 2016 on issues relating to the proposed Office of Missing Persons (“OMP”), submitted to the Consultation Task Force, as well as to respond to the Government’s presentation on 9 May 2016 about the OMP. At the briefing on 9 May, your Ministry presented an outline of the OMP to a select group of civil society members. Responses to the outline were invited within a two-week period.

- The submission below must be read in light of the following serious concerns with respect to process: the two-week deadline to make submissions in relation to the OMP is insincere and in breach of the Government’s initial commitments to hold genuine island-wide consultations with affected communities and civil society. This concern is further reinforced by the fact that the Consultation Task Force will not have adequate time to conduct comprehensive island-wide consultations as per its mandate. It also does not provide the Working Group with the time required to review, consider, and include submissions on content into the proposal they are drafting before it is submitted to Cabinet.

- The 9 May meeting was hastily convened, for a select group, the majority of whom were from Colombo. The two-day notice meant that many, particularly those outside Colombo, who work directly with families of the missing and disappeared, could not attend. While requesting responses to the outline within two weeks, the Ministry refused to share the presentation at the briefing, and the only written document (a leaflet) was emailed to a few civil society members on 13 May for dissemination. This leaflet, according to those at the briefing, does not entirely reflect the substance proposed on 9 May. Further, the short time period proposed by the Ministry does not permit credible consultations with affected persons. There is also the difficulty of commenting on the OMP in isolation without any knowledge or details about the other transitional justice mechanisms contemplated.

- Subject to the above limitations and following a wider discussion, we share below, our comments and concerns, with respect to the process and substance of the proposed OMP.

Feedback on briefings by the Foreign Ministry and Working Group

- In principle, we welcome the effort to share a rough outline, albeit delayed, of the OMP with civil society, and the acceptance of the proposal to hold another briefing for families of the missing and broader civil society on 20 May 2016. However, we strongly feel that both meetings cannot substitute for broader consultations with victim families and affected communities.

- It is regrettable that the Government’s Working Group has failed to consult with families or civil society, in the eight months that it took to develop the draft outline. Unlike the Consultation Task Force, the identity of the Working Group was not publicly known, and was therefore inaccessible to stakeholders. Families of the missing and disappeared are organised, have a deep sense of concern and ownership over any mechanism that deals with the issue of disappearances, and are capable of contributing to this discussion. Significantly, they have been contributing to consultations on the OMP at the behest of the Consultation Task Force. The process adopted by the Working Group and your Ministry disregards their contribution and/or renders it futile.

- At the 9 May meeting, the Consultation Task Force stated that a summary of submissions received so far was submitted to the Working Group on Friday (6 May). While a summary may be expedient for the purposes of the Ministry, the technical Working Group should have the benefit of all submissions on the OMP, in full. So far, there has been no acknowledgment of submissions received by the Consultation Task Force, and the summary submitted to the OMP on the eve of the 9 May briefing, is still not publicly available.

- Crucially, the timeline suggests that the consultation submission and/or summary would have had minimum input into the final outline shared on 9 May. The initial deadline for submissions was 1 May. The interim summary was purportedly handed over on 6 May. By 9 May, the outline had been shared with the President, the Prime Minister, and the Opposition, and the latter had already sent its responses. Given the above, it is unclear the extent to which written submissions have contributed to the proposed outline. We urge that far more credible consultations must take place before the outline passes into law.

- We fail to understand the sudden urgency in this Government’s approach to the OMP, barring political exigency, especially since it was clarified that the rush to finalise the OMP was not in response to international pressure or keeping in mind the next meeting of the Human Rights Council in Geneva. Given the eight-month gestation period, we believe that none of the above concerns would have prevented broader consultations with stakeholders, considering international agencies were

- We urge the Government to go beyond one-off meetings with stakeholders and to engage in real and effective consultations on the OMP before the outline passes into law. We also expect the working group to give reasons where their proposed design features of OMP differs materially from views expressed to the Working Group or Task Force by significant sections of the affected people and/or civil society.

Feedback on substantial issues based on presentations during the meeting and the OMP leaflet

- Based on the Government’s briefing on the OMP on 9 May, and the subsequent leaflet shared on 13 May, there are a number of significant concerns relating to the substance of the OMP we would like to raise. We raise these concerns as, in our view, there was insufficient detail provided in the presentation and the leaflet, and we believe these matters will have a significant impact on the functioning of the OMP. This section should be read together with our detailed submission of 1 May on the OMP to the Consultation Task Force.

- Criminalising enforced disappearance. It is unclear when and how enforced disappearance will be criminalised, both as an ordinary crime and as an international crime. As addressed in our Memorandum, the criminalisation of enforced disappearance must occur prior to the creation of the OMP.

- Temporal mandate. We welcome the proposal that the OMP will have an open temporal scope, and that it will be able to consider missing persons from any time period. While the time the missing or disappearance incident occurred is one appropriate basis for prioritising the work of the OMP as proposed, we emphasise that this should not be the only basis. The availability of adequate information and evidence already pertaining to a case should also be criteria for prioritisation.

- Information given to families. The discretion given to the OMP in providing regular updates to the families is problematic. Families have been waiting for years (sometimes decades) for information about their loved ones, and enquiries into their whereabouts, even before courts, have taken years. Therefore, it should be mandatory (a statutory requirement in the OMP legislation) that families are provided updates whenever there is a development on their respective file and at least once a year, irrespective of any development or outcome of the tracing inquiry. Further, families should be given all available information (subject to information given under confidentiality), not simply summary information from the file. Even if the OMP does not suspect criminal activity, families, in possession of the information from the OMP, should be able to invoke legal remedies independently.

- Definition of family member. While noting that the OMP outline considers the widest definition of family and relatives, there must also be guidelines on how family members and relatives are defined for the purpose of the OMP, especially where there are multiple claims with respect to the same missing person.

- Reparations and interim relief. Given that the OMP, as it is conceived now, will not address reparations, whether interim or final, it is unclear where families should go to seek assistance due to them in the form of reparation for having one of their family members disappeared. It is also unclear how long families are expected to wait until the Office for Reparations will be created, in addition to the length of time already passed since the end of the war. There is an urgent need for prompt reparations to be given to families, as many of them are in dire circumstances. Further, such a move would help promote the on-going reconciliation programme. This is again a less controversial mechanism that can be construed as another ‘low hanging fruit’. Therefore until a full-fledged office of reparations is created, we urge the Government to prioritise and develop a comprehensive reparations policy based on national consultations. The policy shall not privilege one class of victims over the other and should provide for interim relief that kicks in immediately. Once an over-all reparations policy is created, the determination of eligibility, individual assessments, and distributions for the families of the disappeared could be done by the OMP, since it is the body that will have the most interaction with these families. In addition the OMP should definitely have the ability and resources, to cover the costs of families engaging with the OMP (including travel, food, accommodation, and other related costs involved), based on need.

- Mass graves and human remains. The discussion on mass graves should be expanded to include any discovery of human remains. The forensic methodologies of tracing must be consistent with the highest standards of investigations, and any forensic evidence uncovered during the tracings must be handled in such a manner that it can be used for subsequent prosecutions.

- Tracing inquiries. It is unclear the type of inquiry envisaged for the ‘tracing inquiry’ and the standards of evidence to be used. As the OMP will have the ‘first go’ at evidence, both physical and witness evidence, it is crucial that procedures used and standards adopted by the OMP will not detrimentally impact on later criminal investigations. In terms of powers in the conduct of tracing inquiries, we note that the OMP shall have all powers under the Commissions of Inquiry Act and the Special Commissions of Inquiry Act, plus additional powers. In particular, we urge that the OMP’s powers should include the power to receive statements under oath, that the term ‘person’ for the purposes of the OMP includes departments and corporate entities, and that it should have unfettered power to call for records and co-operation from any state body, including the military.

- Existing information and evidence. As addressed in our Memorandum, the OMP must rationalise and analyse the evidence that already exists in relation to missing and disappeared persons, prior to gathering further evidence and prior to engaging with families. The information available from previous Commissions of Inquiry and other investigative mechanisms must be used, in particular to ensure that any duplication of missing and disappeared persons is resolved as a primary matter. The OMP must first (1) create a list of confirmed missing and disappeared from the previous Commissions of Inquiry and other investigative mechanisms, (2) collate all information and evidence about each of those persons to create individual victim files, and (3) determine which persons from that list currently, as at today, have an unknown fate and whereabouts and (4) inform those families so that it is clear whose cases are being pursued by OMP. Based on the presentation and leaflet, it is unclear if this vital preliminary function will occur.

- Certificates of absence. In our Memorandum, we submitted that the OMP should be charged with issuing certificates of absence. If the OMP will not be issuing certificates of absence, the OMP must have powers to issue binding directives to the relevant authority to issue certificates of absence and/or death certificates. Where proof of death is inconclusive, families should have a say in whether a certificate of absence or death certificate is issued. In the absence of proof, families should not be made to accept a certificate. Further, the concept of certificates of absence is directly linked to the transitional justice process and mechanisms, and as such, there should be public consultations on the Government’s proposed framework and process for certificates of absence. This should begin with the Government, as a matter of priority, making information about the proposed certificates of absence scheme publicly available, in all three languages.

- Victim and witness protection. We welcome the proposal that the OMP will have a separate victim and witness protection unit. This unit must also include persons not from the state, particularly those who have practical experience and expertise in protection, professionals from relevant fields, and those who have worked closely with families of missing and disappeared persons. As “Threatening, intimidating, or improperly influencing, any person who has co-operated, or is intending to co-operate with the OMP”[1] will be an offence, the OMP should liaise with relevant agencies/state security forces in order to ensure a conducive environment for those engaging with the OMP. It is also important to ensure that victim and witness protection continues, even once the results of the tracing inquiry are submitted to prosecutors, either through the OMP unit or another equivalent body.

- Psychosocial support. As addressed in our Memorandum, psychosocial support to victims and families should be a core function of the OMP. According to the presentation, psychosocial support will fall within the victim and witness unit. In our view, there must be a separate and dedicated unit to handle psychosocial support issues. The extensive trauma suffered by victims and families, which continues today, requires a comprehensive approach by a specialist and adequately resourced separate unit. In addition to the responsive/reactive role of the psychosocial unit, the OMP itself must proactively organise its engagements with the affected people with the aim of helping them through their grief/trauma and should be mindful in its conduct and not do more harm. This should be a primary rationale in designing the OMP.

- It is unclear what the parameters of confidentiality will be in the OMP. The circumstances in which confidentiality will apply must be made explicit. Further, the use of confidentiality must not occur in a way that hinder victims’ rights to justice.

- Incentives to provide information to the OMP. The OMP’s tracing inquiries must occur in tandem with criminal investigations, to enable the OMP to be in a position to provide incentives to witnesses, in particular to perpetrators, to provide information. In order for the OMP to make decisions regarding the provision of incentives which are adopted in ordinary criminal justice situations (such as guarantees against prosecutions, plea bargains, and reduced sentences), it must work together with a prosecutor.

- Prosecutions. Noting that the ‘relevant authority’ charged with conducting prosecutions will be an entity within the transitional justice mechanisms, there must be greater clarity with respect to the categories of crimes that it will be mandated to prosecute. Further, with respect to criminal investigations, noting the statement by the working group on 9 May, that this will not be conducted by the Terrorism Investigation Department (“TID”) or Criminal Investigation Department (“CID”), there must be more information as to who will be tasked with this work. This is linked to the right to justice of families of the missing and disappeared, which under the current scheme is not contemplated under the OMP. Given that the OMP will begin work before the other mechanisms are set up, there must be clarity on which authority would take on the role of criminal investigations and prosecutions until the transitional justice mechanisms are operationalised.

If these tasks were to be handed over to the police or the Attorney-General’s Department in the interim, which is extremely undesirable from a victim’s perspective, there must be a system of checks to address the lack of confidence and trust among families of the missing and disappeared in government institutions, particularly state intelligence agencies. The system of checks must include stringent vetting of the officers involved, direct supervision and tracking by the OMP, and oversight by international experts. Under no circumstance should officers (present or former) of the TID or those in the AGs department who had had involvement on these cases during the previous regime, including in international fora be included in any function of the OMP. Further, clarity is needed about the authority that will prosecute when the mechanism to deal with prosecutions, which we understand to be the special court, ceases to exist (if it is not created as a permanent court).

- Transferring evidence for prosecutions. Bearing in mind victims’ rights to justice, we believe that all evidence uncovered during a tracing inquiry relating to any domestic or international crime must be made available to prosecuting authorities (in the existing criminal justice system and the special court). However, responding to the provisions of the proposed outline which only contemplates limited information (regarding the identity and/or last known place or location) being submitted to the prosecutor where there is ‘clear evidence’ of a crime, we believe that there must be more guidance on the threshold requirement for what constitutes ‘clear evidence’ and who will make decisions on ‘clear evidence’.

It is important that the OMP is not granted an unfettered discretion in this respect. The leaflet of 13 May states that where there is suspected criminal activity “civil status information of the missing person”[2] will be handed over to investigative authorities. There must be greater clarity on what is meant by “civil status information” and if it means that substantive evidence will not be transferred. It is also unclear what will happen to evidence that does not reveal clear evidence of a crime, but nevertheless is integral to establishing the context for international crimes. There is great danger in excising portions of evidence as it detracts from considering the criminal consequences of the totality of the evidence, including as necessary for systematic crimes. As it appears that the OMP will be the first of the transitional justice mechanisms, it will be the institution that will be privy to, and house the largest volume of evidence. It is unclear whether the special court or other prosecutor will have access to this vast catchment of evidence. Further, the OMP will be privy to evidence of criminal activity beyond enforced disappearances. It is unclear how this evidence will be accessible to prosecutors.

- Jeopardising evidence for prosecutions and witness impeachment. It is unclear how the Government will manage the issue of potential witness impeachment at trial, given, it appears, that the OMP will not co-ordinate its inquiries with criminal investigations. Requiring a witness to give evidence multiple times (in addition to the already existing witness evidence), in these transitional justice mechanisms is dangerous: memory is inherently unreliable and consistency becomes an issue, leading to witness credibility issues, which ultimately has the potential to jeopardise prosecutions. For this reason, we reiterate that the criminal investigations must occur in tandem to the OMP tracing inquiries.

- Guarantee of non-recurrence. The current outline does not contemplate recommendations by the OMP on guarantees of non-recurrence, specifically with respect to enforced disappearances. Bearing in mind that non-recurrence is a critical pillar in any transitional justice mechanism, the OMP must be given the power to make binding recommendations to Government on measures to guarantee non-recurrence, with a concurrent obligation on Government to give effect to such measures/recommendations.

- Involvement of foreign nationals. The involvement of foreign nationals as staff and advisors, based on the needs of technical expertise and trust-building, must be given serious consideration and clarified. A process of appointments for such personnel must be put in place, jointly by Sri Lankan authorities and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- OMP’s relationship to other transitional justice mechanisms and the criminal justice system. It is unclear how the OMP will interrelate with the other transitional justice mechanisms and existing criminal justice institutions. The extent of the powers envisaged for the OMP and how they relate vis-à-vis other institutions is also unclear. It appears that the OMP will have wide discretion in a number of areas.

- Organisational structure. It is unclear how the OMP’s organisational structure will be set out. There must be a clear statement about the structure of the OMP, including how the different units of the OMP will interrelate with each other.

- Composition of the OMP. The presentation and leaflet do not specify gender and ethnic representation of the OMP. It is important that the composition of the OMP be representative, particularly with respect to gender and ethnicity.

- Tamil speakers and staff. As addressed in our Memorandum, the OMP must have sufficient numbers of Tamil speaking staff, as a large number of the persons with whom the OMP is going to deal with, are going to be Tamil speaking. This should include not only interpreters and translators, but also persons who could correspond with the families of missing and disappeared persons in their own language.

- Branch offices. Given that families of missing and disappeared persons largely reside in different parts of Sri Lanka, outside of Colombo, we welcome the proposal that the OMP will have branch officers in the Districts. If families are required to engage with the head office, if it is in Colombo, families should be adequately compensated for travel.

- Public outreach. The OMP must encourage as many people as possible to provide information and establish appropriate public outreach tools and messaging, such as mainstream and social media, existing government infrastructure, and a hotline which could offer confidentiality and anonymity to informants.

- Disciplinary action. For suspected perpetrators who are serving military, law enforcement personnel, or civilian government officials, where there is credible material indicative of a person’s responsibility in an alleged disappearance, information should be made available to the respective institution to consider disciplinary action.[3]

Recommendations to the Foreign Ministry/Government

- Make public, in all three languages and in writing, through mainstream media and other structures of the Government, a more detailed and comprehensive version of the Government’s proposal for the OMP, including the information that was presented at the meeting of 9 May 2016. This should also be the case for the three other transitional justice mechanisms that the Government has committed to establish and the confidence building measures the Government has committed to take.

- Make public, in all three languages and in writing, ALL submissions that have been received by the Consultation Task Force (subject to submissions received on the basis of confidentiality), and ANY summary or other document (created based on the submissions received) that was (or will be) sent to the Working Group.

- In the interest of the broader ownership of the OMP, reconciliation, and transparency, make public the working of the Government’s Working Group that has been entrusted with drafting the concept note and outline for the OMP. This should include the names of the individuals and their expertise, mandate, and time frames for the outcomes of work. Further, to state publicly if the Working Group are currently working on other drafts, and if so, how the Working Group will benefit from the public consultations conducted by Task Force. We urge that there be a structured process of engagement between the Task Force and the Working Group.

- Make public the timeline for setting up the OMP. For example, the dates for placing the OMP proposal before Cabinet, tabling draft legislation in Parliament, the time that will be given for public comment after tabling in Parliament, the estimated time for the OMP law entering into force, and the estimated time for the OMP to become functional (to start working). It is imperative that sufficient time is given in the legislative process for stakeholders to assess and comment on the proposed law. Once the Bill to create the OMP is tabled in Parliament, there must be at least a two-month period where families of the missing and disappeared, civil society, politicians, and other stakeholders have the opportunity to digest, analyse, and comment on the proposed OMP. This should also be the case for the three other transitional justice mechanisms that the Government has committed to set up.

- Ensure the Consultation Task Force has adequate time, human and financial resources, and the independence to carry out island-wide consultations on the OMP and the other proposed transitional justice mechanisms. Also, clarity is needed about the scope for review that exists if the Consultation Task Force comes with new recommendations with respect to the OMP after the public consultations have been completed (for example, whether the OMP will be able to establish by-laws and guidelines and if the Government will be bringing in amendments). The OMP should become operational within three months from the time the OMP Bill is passed into law.

- The complementarity and links (if there is any) between the “briefing” by the Foreign Ministry and the Working Group and the “consultations” by the CTF should be clarified.

- Clarify whether civil society and all others should provide feedback on the OMP through the Task Force or also to the Working Group and the Foreign Ministry. Also, whether civil society can continue to provide input on the OMP through the Task Force, as long as it is conducting consultations, beyond the limit of two weeks given on 9 May 2016.

- Criminalise disappearances (both as an ordinary crime and an international crime) and ratify the Enforced Disappearance Convention,[4] including explicit recognition of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances under Article 31, before a draft Bill of the OMP is put before Parliament and make public the time line for this. Ensure also adequate time and resources for consultations on criminalisation. Enforced disappearance must be operative law prior to the OMP beginning to function.

- Ensure the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act[5] happens before the OMP is operationalised. Any new laws in relation to national security/counter terrorism must be in line with international human rights standards and are enacted only after adequate consultations with all interested and concerned parties.

- Ensure that there are no “white vanning” (abductions) in the lead up to the OMP, investigate recent reports of abductions, and ensure those responsible are held accountable

Yours sincerely

- Swasthika Arulingam.

- Marisa De Silva.

- Shenali De Silva.

- Ruki Fernando.

- Balachandran Gowthaman.

- M C M Iqbal.

- Gajen Mahendran.

- Deanne Uyangoda.

16 May 2016.

Copy to:

- Hon Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister.

- Consultation Task Force.

- Hon Dr Wijeyadasa Rajapakse, Minister of Justice.

- Hon Jayantha Jayasuriya PC, Attorney-General.

- Hon Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Co-existence Dialogue and Official Languages.

- Hon Rajavorothiam Sampanthan, Leader of the Opposition.

- Madam Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, Chair, Office for National Unity and Reconciliation.

- Mano Tittawella, Secretary-General, Secretariat for Co-ordinating Reconciliation Mechanisms.

- Dr Deepika Udagama, Chair, Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka.

- Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Houria Es-Slami, Chair-Rapporteur, UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances.

- Claire Meytraud, Head of Delegation, International Committee of the Red Cross Sri Lanka.

- Andreas Kleiser, International Commission on Missing Persons.

[1] Secretariat for Co-ordinating Reconciliation Mechanisms, Proposal for the Office of Missing Persons (OMP), 13 May 2016, p 2.

[2] Secretariat for Co-ordinating Reconciliation Mechanisms, Proposal for the Office of Missing Persons (OMP), 13 May 2016, p 1.

[3] See Final Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Involuntary Removal and Disappearance of Persons in the Central, North Western, North Central and Uva Provinces, The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, Extraordinary, No. 855/18, 25.01.1995 (“Central Commission”), Part I, p 3, para 3.

[4] International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, adopted 20 December 2006, UN Doc. A/61/488 (entered into force 23 December 2010) (“Enforced Disappearance Convention”).

[5] Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act No. 48 of 1979.