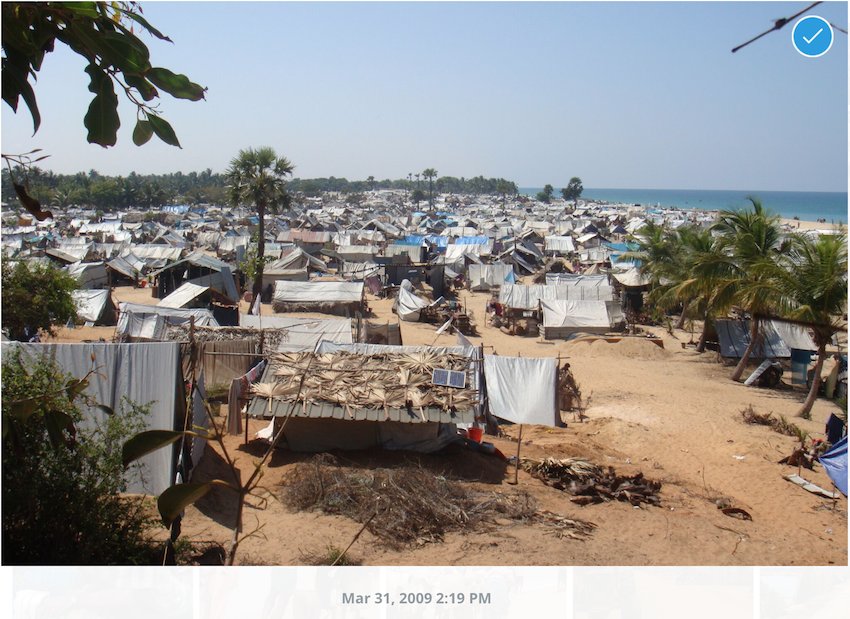

Image: Vanni no fire zone at the end of the war.

On Monday 23rd October, the UN Special Rapporteur on Transitional Justice, Pablo de Greiff, issued his concluding observations and recommendations following a two-week official visit to Sri Lanka – in essence, a review of the government of Sri Lanka’s progress in addressing the country’s legacy of mass human rights violations, including those committed during the final stages of the recent civil war which saw thousands of (mostly Tamil) civilians killed.

You can read the statement in full here. Or you can check out some of the key excerpts from it, along with our analysis, below.

What does the Special Rapporteur say?

In line with our own evaluation on whether the government is fulfilling its promises to deal with the past, the Special Rapporteur’s statement paints an alarming picture of how little ground the government of Sri Lanka has covered on the road to reconciliation and sustainable peace. While acknowledging some very limited areas of progress, his headline conclusion is plain: “the process is nowhere close to where it should have been more than two years [since his first visit in April 2015].”

In this context, the statement provides some much-needed reminders: both about the costs which ordinary Sri Lankans continue to pay – as well as the benefits which those from all communities are deprived – as a result of the government’s heel-dragging. These, the statement suggests, are measureable not simply in terms of the denial of justice to the many victims of human rights abuses in Sri Lanka, but also in terms of levels of continued inter-ethnic violence, human well-being, and economic development more broadly.

Strong on bringing perpetrators to account…

The statement also makes a number of welcome noises on the question of accountability for the perpetrators of human rights violations, in particular, by challenging recent vows by senior members of the Sri Lankan government to protect so-called ‘war heroes’ [i.e. members of the Sri Lankan armed forces] from prosecution for serious crimes. “No one who has committed violations of human rights law or the laws of human rights deserves to be called a hero”, the Special Rapporteur writes. Moreover, such promises by the government are in any case, he points out, “legally unenforceable political statements” – ineffective internationally in the context of recent efforts to bring alleged Sri Lankan war criminals to justice in foreign jurisdictions.

…but what about the accountability mechanism?

It is also on the subject of accountability, however, that the Special Rapporteur’s statement has raised some concerns among sections of Sri Lankan civil society. Despite repeated references to the importance of justice in the abstract, there is no re-affirmation (or indeed mention whatsoever) of the specific kind of justice mechanism which the government of Sri Lanka itself has pledged, and which war survivors have repeatedly said is needed – that is, a “judicial mechanism with a special counsel”, with the participation of international judges, prosecutors, defence lawyers and investigators. In February, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights referred to such international participation as a “necessary guarantee for the independence, credibility and impartiality of the process.” Instead, recommendations are focussed on the need for capacity-building towards a “future reliable accountability system”, and on shifting the debate away from the “nationality of judges” to the “means and preconditions for the establishment of credible procedures”.

However well intentioned, we at the Sri Lanka Campaign are concerned about the green-light that such messages could provide for the establishment of an accountability mechanism which, without some form of independent international involvement, is neither reliable nor credible. Indeed, given the closing window of opportunity for reform which the Special Rapporteur himself appears to acknowledge, we fear that the lack of strong messaging on the need to legislate for a judicial mechanism in the here and now may compound the risk of nothing at all being established under the current government. That outcome would represent the denial of justice to thousands of war affected individuals, as well as the increased danger of future human rights violations resulting from the failure to tackle Sri Lanka’s deep-rooted culture of impunity.

Next year, the Special Rapporteur will present the full report resulting from his visit to the September session of the UN Human Rights Council. It will come at an important moment – just six months ahead of the March 2019 session, when the clock will once again run down on formal international scrutiny of the government’s commitments to dealing with the past (originally pledged in October 2015, and already renewed once in March of this year).

With UN member states increasingly appearing to shy away from applying the kind of diplomatic pressure that is so needed to bring about a meaningful accountability process in Sri Lanka, robust and coordinated leadership on this issue from UN bodies themselves – including the Secretary General’s Office, the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the Special Rapporteurs – will be needed more than ever during this critical period. We urge them to ensure that is the needs and wishes of war survivors, who have called for the establishment of a credible independent mechanism without delay, that guide them above all in this regard.

- Sri Lanka Campaign