The Parliament of Sri Lanka has 225 member seats. The 22 electoral districts elect 196 seats. Each party receives seats in proportion to the votes it received in that district. The remaining 29 seats are the “national list”. Each party receives national list seats, in proportion to the votes it receives islandwide.

At first glance, it might seem that our proportional representation system is indeed “proportional”. The reality is different. And that is what this article discusses.

District Level Disproportionalities

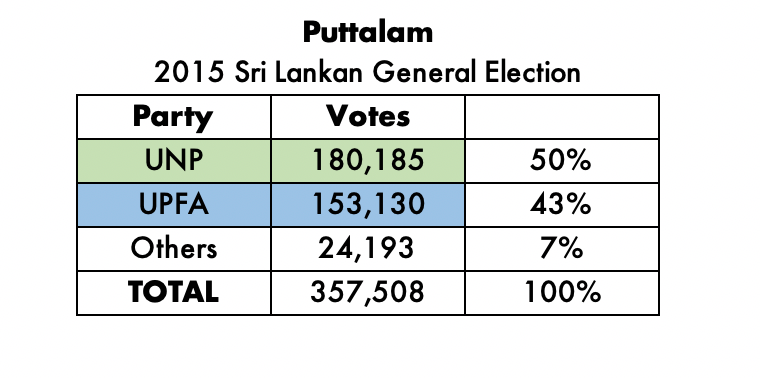

The Puttalam electoral district has 8 seats. In the 2015 general election, the UNP got 180,185 votes, the UPFA 153,130 votes, while other parties got 24,193 votes.

If we were to allocate the 8 seats exactly proportionally, the UNP, UPFA and Others would get 4.03, 3.43 and 0.54 seats respectively. Since we can’t allocate fractions of seats, we could round these numbers to get 4, 3 and 1. This might seem like a fair allocation.

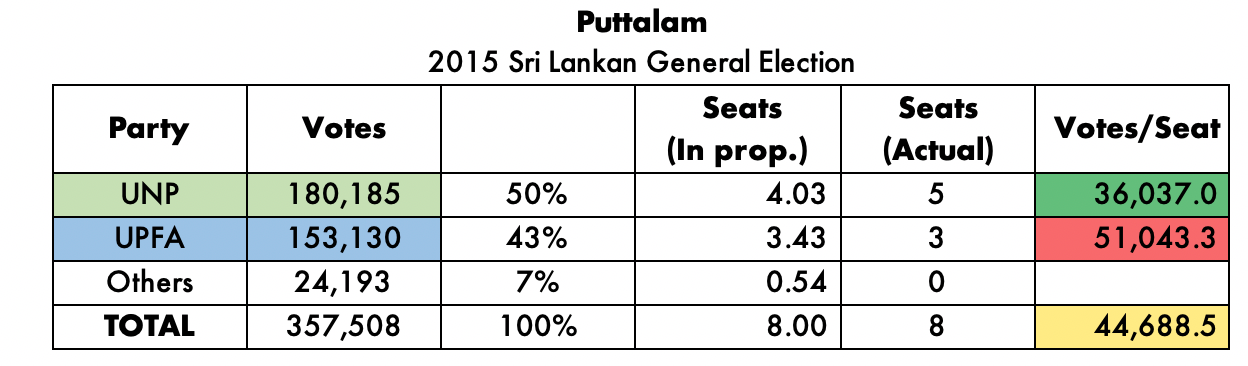

In reality, the UNP got 5 seats, the UPFA 3 seats, and no seats were allocated to the other parties. There are three reasons for the “unfairness”.

The Bonus Seat

First, according to our constitution, the party with the highest votes of each electoral district gets a “bonus seat”. Hence, the UNP got 1 bonus seat. Thus, even if a party is “highest” by just one extra vote, it gets a bonus seat.

The 5% Limit

Second, parties receiving less than 5% of the vote, don’t qualify for seats. Hence, none of the “Other” parties (all of which got less than 5%) got seats. It also means that the parties that do end up getting more than 5% need fewer votes per seat.

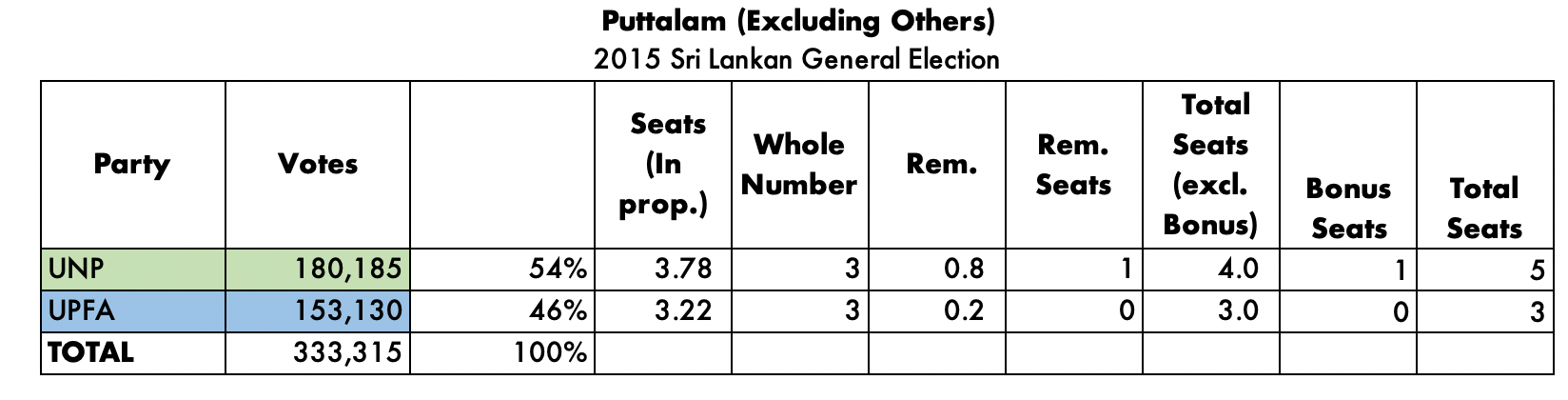

The remaining seats after allocating the bonus (In Puttalam’s case, 7), are allocated proportionally to the parties that have more than 5% of the total vote, using the “Largest remainder method”.

The Largest Remainder Method works as follows:

- Step 1. Each party is allocated a rounded-down whole number of proportional votes

- Step 2. The remaining votes are allocated to the party or parties with the largest remainder

For example, excluding the “Others” and dividing proportionally, the UNP and UPFA should get 3.78 and 3.22 seats respectively. Hence, each is first assigned 3 seats each.

This leaves remainders of 0.78 and 0.22 for the UNP and UPFA, and one remaining seat. Since the UNP has the highest remainder, it is assigned the remaining 1 seat.

Rounding Luck

Hence, thirdly, because of rounding, a party could get a lucky round-up, or an unlucky round-down.

The final effect is that the UNP got a seat for every 36,037 votes, and the UPFA got one for every 51,043. The others, despite getting 24,193 votes, got no seats.

National Level Disproportionalities

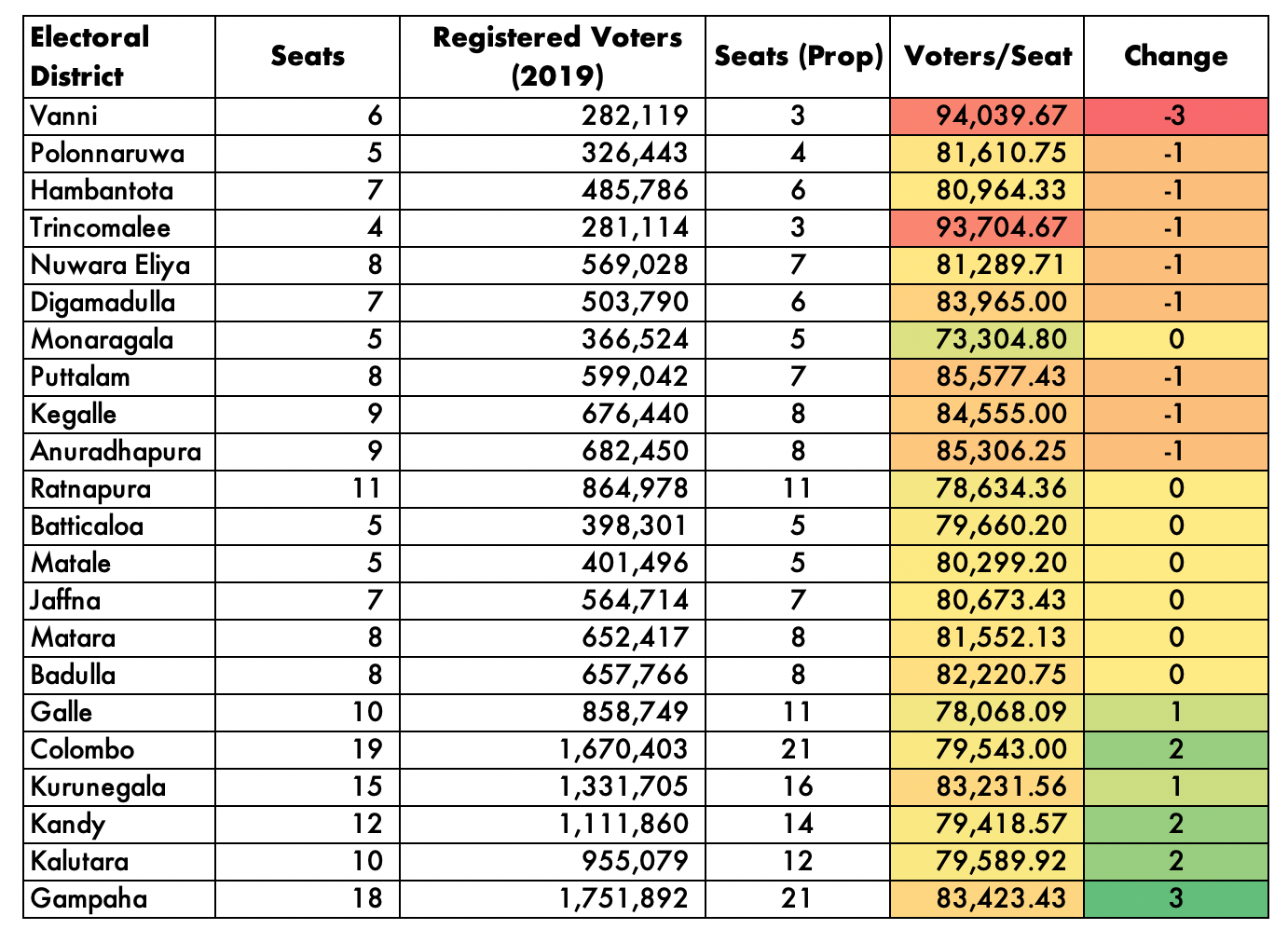

The recently concluded 2019 presidential election had 15,992,096 registered voters. Hence, we could expect the 196 electoral district seats to be allocated for every 81,592 votes. However, if we compare “registered voters/seat” across districts, there are significant differences.

At one extreme, Gampaha district has 97,327 voters per seat. At the other, the Vanni district has 47,020 per seat, or less than half of Gampaha. Overall, we notice districts with small populations have fewer voters per seat.

What is the reason for this difference?

Not all the 196 seats are allocated to electoral districts in proportion to voter population. Only 160 are. The remaining 36 are equally allocated to each of the 9 provinces. Or 4 per province.

Hence, the Western province (with over 4M registered voters) and the Northern province (with 800K registered voters), gets the same 4 seats each.

Thus, it is easier (i.e. you need fewer voters) to win a seat in a smaller province.

An Alternative (but currently unconstitutional) Allocation

If we assigned the 196 in proportion to the district’s registered voters (using the same Largest Remainder Method), the allocation of seats would be as follows:

The smaller districts would have fewer seats. The larger would have more. And the ones in the middle would have no change. But the Voters/Seat is much fairer.

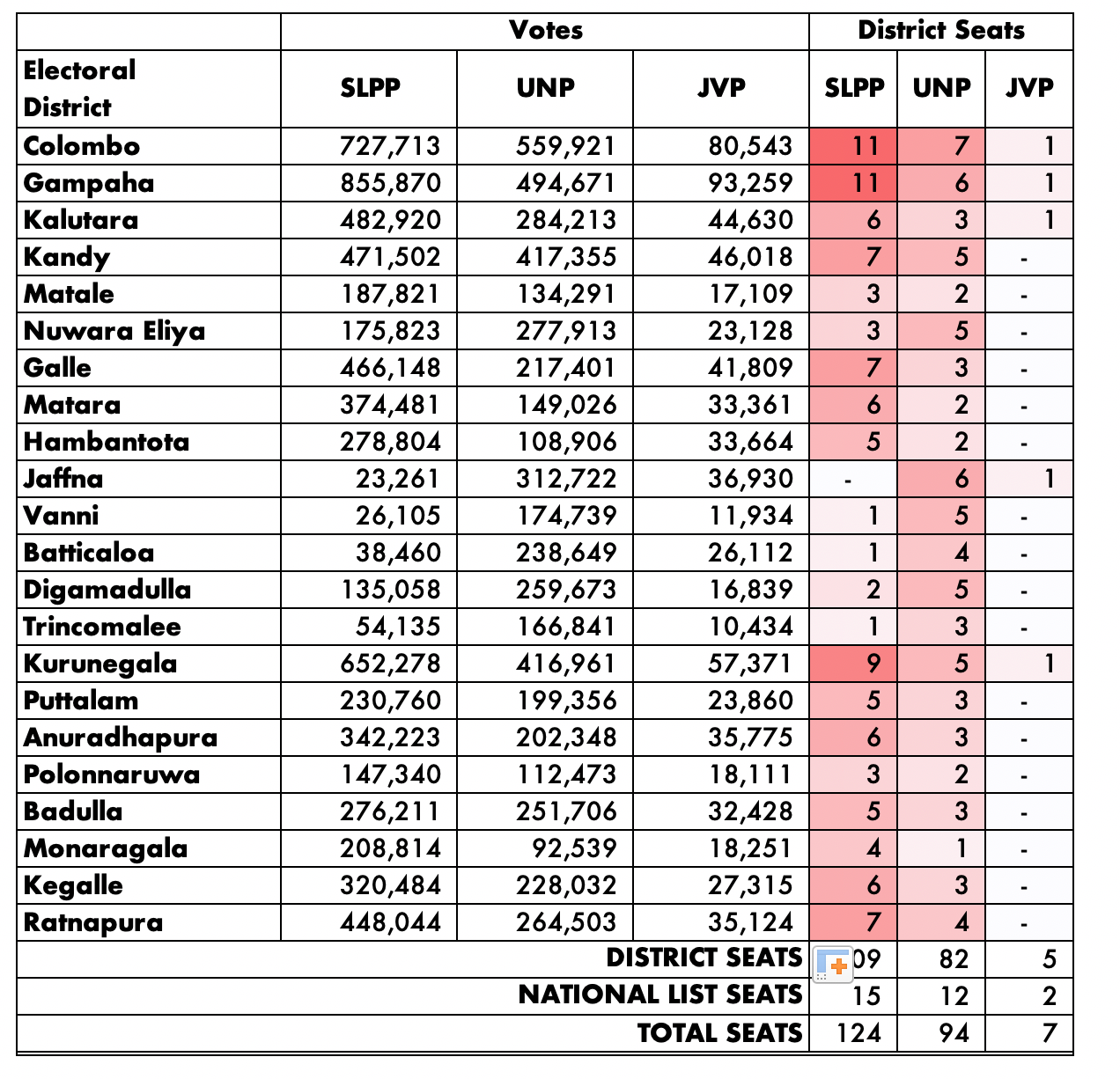

A Hypothetical Example

(Not a prediction for the next general election)

Suppose the next general election has the same results (party-wise) as the recently concluded presidential election. Also, suppose we are generous and assign all the “Other” votes to the JVP (very generous).

Then, by our current not-so proportional representation scheme, each party would receive the following numbers of seats.

By our alternative properly proportional scheme:

Concluding thoughts

I’m not sure what the thinking behind the “bonus” and the 36 seats for the provinces was. Either way, these asymmetries seem to cause some unfairnesses. Though, it is unclear (to me) how significant these are.

Courtesy of medium.com