As crisis-stricken Sri Lanka reluctantly turns to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for urgent financial assistance this month, dozens of parliamentarians have urged Britain to use its influence at the global institution to attach conditions that will ensure there is deeper-rooted change and political stability on the island.

The day before Sri Lanka declared it would be unable to repay US$ 51 billion in international debt, a group of 90 British lawmakers urged the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer to add conditions on any IMF assistance that may be granted, “to put the country on the path of economic recovery”.

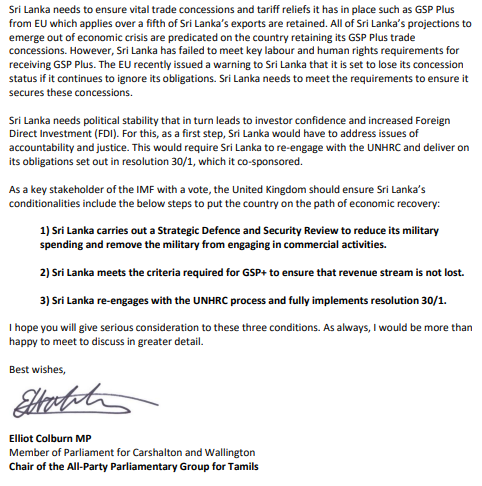

“Sri Lanka has failed to neither seek accountability for the war crimes committed during the civil war and reconcile within its communities nor realise a peace dividend to create an inclusive and equitable economy,” wrote Elliot Colburn, Chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Tamils.

“The cause of Sri Lanka’s financial crisis is not entirely due to economics,” he added.

“They are multifaceted. Failure to include the Tamils in economic activity, a large defence budget to support a disproportionally large military – despite having no real internal or external threat, politically motivated subsidies, corruption, and, of course, poor fiscal policies have led Sri Lanka’s economy to the brink of bankruptcy.”

That brink of bankruptcy has seen soaring prices of basic goods, skyrocketing inflation and the value of the rupee plunging to become what the Financial Times labelled the ‘worst performing currency in the world’. Earlier today Sri Lanka declared “it has come to a point that making debt payments are challenging and impossible,” and admitted that it will be appealing to the IMF for “support”.

Colburn told Britain’s Chancellor Rishi Sunak that this must come with strings attached.

“As a key stakeholder of the IMF with a vote, the United Kingdom should ensure Sri Lanka’s conditionalities include the below steps to put the country on the path of economic recovery,” he wrote, outlining conditions to add, including;

1) Sri Lanka carries out a Strategic Defence and Security Review to reduce its military spending and remove the military from engaging in commercial activities.

2) Sri Lanka meets the criteria required for GSP+ to ensure that revenue stream is not lost.

3) Sri Lanka re-engages with the UNHRC process and fully implements resolution 30/1.

‘The IMF needs to change its approach’

This will not be the first time that Sri Lanka reaches out to the IMF for support, having done so several times since joining in 1950.

However, there has been fierce Sinhala opposition to reaching out to the international institution for support, from across the political spectrum. Earlier this year, The Economist noted that the current regime “has vocally opposed IMF intervention, calling it an infringement of sovereignty”. Parliamentarian Vasudeva Nanayakkara, even went so far as to state, “even if we die, we will not seek assistance from the IMF… This is the final thing I have to say. Even if this Government, our Government gets destroyed, we are not prepared to reach out to the IMF and destroy the lives of our people”.

The remarks came despite current prime minister Mahinda Rajapaksa having appealed to the IMF for a US$2.6 billion loan in 2009, during his previous tenure as president. At the time, Sri Lanka’s rapid expansion of the military and massive war effort cost the regime millions, with expensive weapons purchases from across the globe and depleted foreign reserves.

Mahinda Rajapaksa with Shavendra Silva in 2009. Both men stand accused of war crimes.

Sri Lanka was in the midst of a military offensive that massacred tens of thousands of Tamil civilians. Hospitals were repeatedly bombed, Tamil men and women were subjected to widespread sexual violence, and there were executions as well as forcible disappearances. As many as 146,679 people remain unaccounted for.

As Rajapaksa approached the IMF at the time, more than 300,000 Tamils languished in military run camps in the aftermath of the massacres. Human rights organisations and Tamil activists urged diplomats around the globe to stop the IMF from providing assistance to the Sri Lankan government.

“To approve a loan while they have hundreds of thousands of people penned up in these camps is a reward for bad behaviour, not an incentive to improve,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The IMF needs to change its approach.”

Then-US secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, said that it was “not an appropriate time” to consider an IMF loan to Sri Lanka, whilst then-UK foreign secretary, David Miliband, also commented “it is essential that any government is able to show that it will use any IMF money in a responsible and appropriate way … I don’t think that that’s the case here.”

“The IMF board of governors should make the release of each new tranche of funds contingent on tangible human rights progress,” added Adams.

Though the assistance was eventually approved – saving Sri Lanka from a looming balance of payments crisis – several countries including the United States and Britain abstained at the vote. For the UK, the decision to abstain was the first since 2004, and sent a powerful signal to the Sri Lankan regime.

Stephen Timms, then-Financial Secretary to the Treasury, said in a letter to MPs that the UK “did not support the IMF’s proposed Stand-By Arrangement” and that his government “believes that it is not the right time for this programme to be taken forward”.

“In this context, we believe that the political situation in Sri Lanka poses risks to programme implementation,” he added.

A British government source told The Times after the vote that Britain would “look to see that military expenditure falls appropriately over the course of the programme, facilitating greater spending on social programmes and reconstruction”.

‘We will look closely at any future IMF programme for Sri Lanka’

In the years that followed however, Sri Lanka’s military budget did not decrease. In fact, it went in the opposite direction, with expenditure increasing as tens of thousands of troops remained occupying the Tamil homeland in the North-East of the island.

As the ruling Rajapaksa regime continued to take out costly loans to fund projects such as an airport and seaport in the family’s hometown – some of several ‘white elephant’ constructions that took place – soon Sri Lanka faced yet another balance of payments crisis. The newly elected Sirisena-Wickremesinghe government turned to the IMF once more in 2015, seeking a US$1.5bn bailout loan to avert a balance of payments crisis.

“Besides economic mismanagement, the core issue of Sri Lanka’s long run economic success is political stability which can only be achieved by reconciliation through true accountability,” wrote the British Tamil Conservatives (BTC) in a 2015 letter to then-Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne.