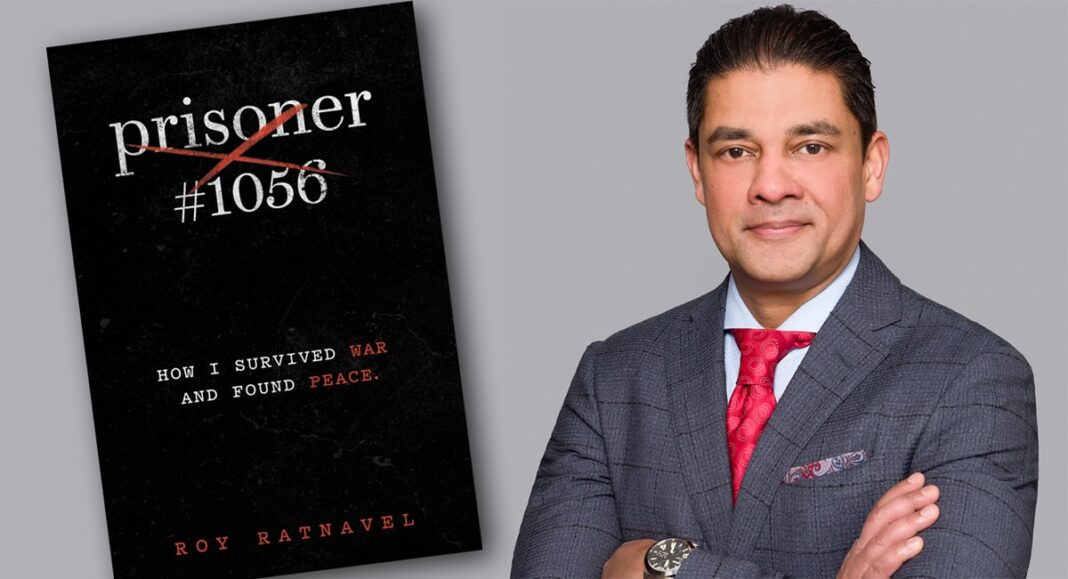

- Strap: The author of ‘Prisoner #1056’, Roy Ratnavel relives his time in prison in SL and his journey thereon in Canada, fuelled by his father’s advice

BY Savithri Rodrigo.

His story is gut wrenching, sorrowful, and awe inspiring. Roy Ratnavel was just 18-years-old when he fled to Canada in search of a new future, having spent months in prison in the aftermath of the Vadamarachchi Operation of 1987. Released from the Boossa Camp where he was imprisoned, Roy’s father realised that the young man’s future was bleak and packed him off to Canada. When his father was tragically shot, Roy was determined to keep his father’s dream alive – the start of his way to the top of the financial landscape of Canada. His journey at one of the largest investment firms in Canada, CI Financial, began in the mailroom. Now an Executive Vice President of the Company, Roy was also named one of the “50 Best Canadian Executives” in 2020. Roy digs into painful wounds with his memoir “Prisoner #1056” which is currently sitting at the number two spot in the list of Canada’s bestsellers and number eight in the “Globe and Mail” bestseller list since its launch just two weeks ago. He gave Kaleidoscope an exclusive interview for Sri Lanka.

Your story is harrowing, astonishing, and extremely engaging. What pushed you to publish your story and why now?

I wanted to publish this book for three reasons. First, to tell a story to the world of a tortured teenager who fled war and oppression from his former birth land. The second is to give a voice to the next generation of Tamil men and women who are coming of age in Canada and in other Western nations, to tell their stories of war and their parents’ stories of fleeing Sri Lanka. And the third is to celebrate freedom and democracy. When people are given freedom and democracy, society thrives and functions, becomes successful and at peace at the same time. This is also my homage to Canada for appreciating differences while existing as a peaceful society.

You have had to overcome almost impossible odds to get to where you are. How did you keep going when things seemed hopeless?

When my father dropped me off at the Katunayake Airport on 18 April 1988, he said: “I don’t want you to survive, I want you to live”. That was my mantra when I came to Canada. I had to honour his word to build a life of prosperity and happiness and I was single minded on that objective.

How did you become prisoner #1056?

I was born in Colombo in 1969 and then a few years after that, my father moved us to the North. Our ancestral hometown is Point Pedro, so my father sent us there, where I continued studying. In May 1987, during “Operation Liberation” organised by the Army, I was rounded up along with 2,500 other young men, put on a cargo ship, and sent to the Boossa Navy Camp. I was 17-years-old.

What was your time in prison like and how did you get out?

Prison was obviously a man made hell. I was one of the luckier ones who got out, as some of my friends never made it. One day, there was an announcement that the Deputy Defence Minister’s wife, Srimani Athulathmudali, would be visiting prison. I asked for the opportunity to speak with her because I wanted to let my parents know where I was as they had no clue.

I remembered my father’s friend Colonel Dudley Fernando’s telephone number (believe it or not) and I gave that to Srimani Athulathmudali, asking her to pass a message on to my “Uncle Fernando”. It was he who got me released from prison.

What was the most important lesson you learned in your time in prison?

I learned that kindness will kill you in prison and that you have to be selfish to survive, which is a harsh statement to make. The fact that I didn’t care about anyone else and fought my way out of the prison is in itself what I call survivor’s guilt. Some of my friends perished in prison and I have to live with that.

You came to Canada at the age of 18-years, alone, with next to nothing. What was your mindset when you landed in Canada?

A: I landed in Canada on 19 April 1988, and two days later, my father was shot and killed by the Indian Army when he was visiting Point Pedro. My father’s untimely death left me with the feeling that if I did well enough in life, I could make up for the life that he should have had, and that single objective became the coal for my furnace of ambition. When he died, a part of me died, but another part of me became a fighter. I wasn’t going to let that incident define me and my future, and I had to honour his words to me: “I don’t want you to survive, I want you to live.”

What are the key takeaways from your book?

A: The only thing that humans need to be guaranteed in life is freedom and choice. When you have that, society will reward you for the good choices that you make and will not reward you, or will punish you, for the bad choices that you make. That is the price of freedom. The other takeaway is that hard work wins. That is a testament to this book. We all need to change and evolve our views and our stance on life and in that respect, for Sri Lankans, the message would be: Sri Lanka could have been much better than what it is today, but it never evolved. It is stuck in the past and focused on ethnic divisions. Canada, on the other hand, is a marvellous example of a country that has people from many parts of the world coming together to work on the single goal of creating an amazing country, which is another message that this book is trying to espouse.

Was the experience of writing your own life story a cathartic one?

It was certainly therapeutic and cathartic at the same time. I broke down a few times as I was writing some of the darker parts, but when I emerged from the whole thing, it was really a book about success more than suffering. It really tells you how resilient the human spirit can be. It can be broken, but not that easily. I feel a lot better after writing the book and telling the stories because I’ve been carrying this with me for 35 years. Letting it go and letting the world know gives me peace of mind.

Yours is an inspiring rags to riches story. Being a migrant who has done well for yourself in the most difficult of circumstances, what would you say to young people starting their lives off in a new country?

While you can’t control outcomes in life, you’re certainly in charge of all the inputs. Opportunities are never lost because someone will take the ones you miss. I truly believe that you don’t deserve what you get, but you deserve what you fight for. So, keep fighting.

If it feels awful when you’re going through the journey, then you’re doing it right. You are one of thousands who has gone through hardship to get to where you are today and I am one example. So don’t ever give up the fight. Take every heartbeat like your last one and go for it. That is my motto.

What are your feelings towards Sri Lanka?

The democratic political system assumes a certain minimum level of ethical behaviour, responsibility, and civility by elected Government officials, explicitly spelled out in the Constitution. If those ethics are absent, then democracy isn’t going to work. Sri Lanka is a sad example of that. In the absence of an overwhelming and fundamental change in the Sri Lankan attitude and behaviour, I think that country will forever be in conflict.

What do you see of Sri Lanka now? What has changed? What has not?

I truly believe that the decline of Sri Lanka’s moral fibre represents the single most serious threat to its survival. I am afraid that, at the core, Sri Lanka hasn’t changed since 1948.

Repeatedly electing the same type of politicians who play racially divisive games has brought this country to its knees. The pattern gets repeated expecting different results, but nothing will change.

Is there anything you want to say to the people of Sri Lanka?

When Sri Lanka gained Independence in 1948, it was considered to be the post-colonial nation most likely to succeed economically and democratically. Unfortunately, since then, Sri Lanka has been governed by leaders with a penchant for racial division. Through that hatred, they have succeeded in destroying the beautiful country. It is heart wrenching to see it. Take your country back by putting some young, inspired leaders with a vision who can bring all communities together with one single goal of peace and prosperity to all.

(The writer is the Host, Director, and Co-Producer of weekly digital programme ‘Kaleidoscope with Savithri Rodrigo’ which can be viewed on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. She has over three decades of experience in print, electronic, and social media.)