Introduction.

With less than two years to the next Presidential election, Sri Lanka is facing one of the most serious political crisis in recent times. In the Local Government elections in February 2018, the party of former President Mahinda Rajapaksa secured the majority of votes in many constituencies, pointing towards a possible political shift. Sri Lanka is now at the crossroads, with looming uncertainty.

The expectations of reconciliation, protection of human rights and accountability in Sri Lanka were based on bi-partisan politics in the South, the willingness of the Tamil polity to find a negotiated political solution and a strong civil society. The post-2015 developments paved the way for establishing checks and balances in form of Independent Commissions and provided a democratic space for the people. Today, however, all these developments and factors that propelled change have come under threat due to the political instability, following the Local Government elections.

On one hand, the much defeated corrupt and suppressive forces led by Rajapaksa threaten to capture power on the basis of Sinhala nationalism. On the other hand, the ruling coalition which came to power on the promise of democratisation, justice, and accountability is being disintegrated.

Read the full report as a PDF:Sri Lanka Briefing Note No 13 March 2018

Political climate

Differences between the two coalition partners of the Government have become issues with far reaching consequences. Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) headed by President Sirisena and United National Party (UNP) headed by Prime Minister Wickremasinghe have taken up contradictory positions on major political, economic and cultural issues, including transitional justice.

President Rajapaksa now commands the support of 52 out of the 98 Members of the Parliament. He also commands absolute majority of local government bodies. Rajapaksa remains the most popular political leader among the Sinhala Buddhist community and has been mobilising his followers regularly. Sinhala Buddhist majoritarianism provides the foundation for his politics.

The ruling coalition did not campaign jointly for an inclusive Sri Lanka. President Sirisena tried to employ Rajapaksa’s Sinhala-nationalist and war-triumphalist populist slogans to widen his own base. This strategy backfired as it strengthened Rajapaksa ideology in the country.

A divided country

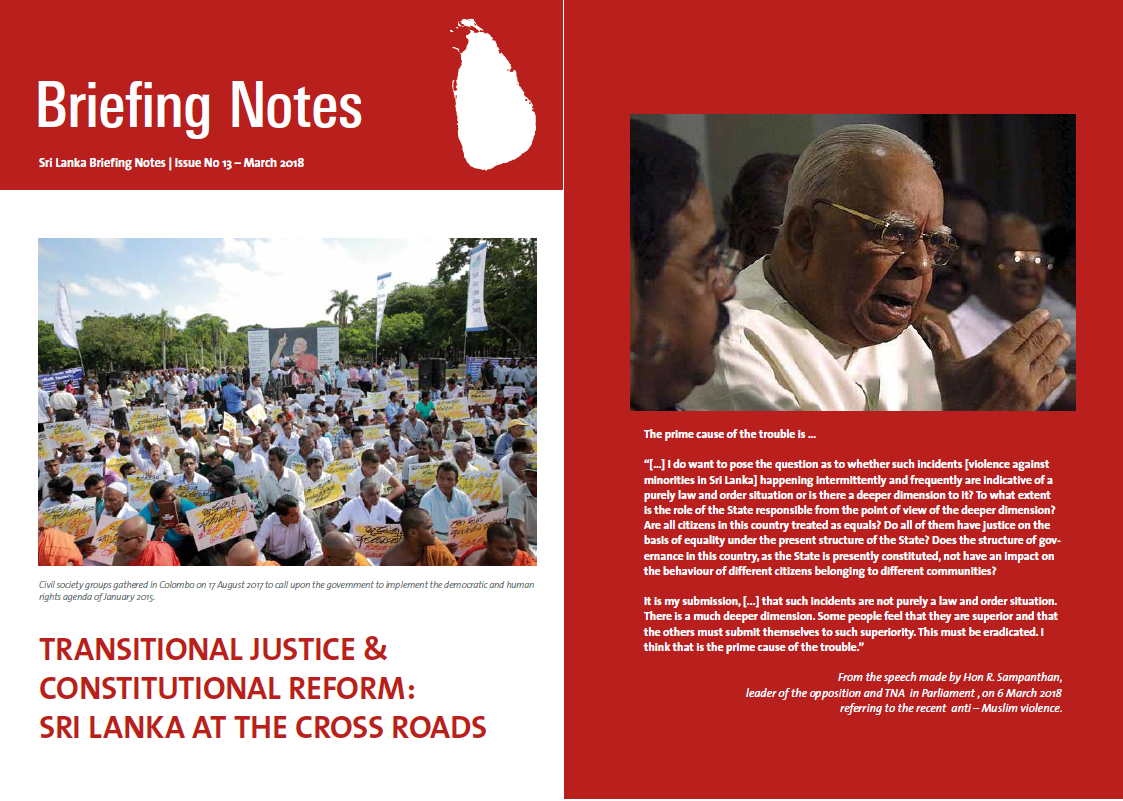

The recent anti- Muslim violence that sent shock waves throughout the country is an indication of the increasingly widening ethnic polarization. In past months three minor incidents that should have been brought under control quickly transformed into anti-Muslim violence spreading like wild fires. These xenophobic attacks reached its climax in the first week of March in the district of Kandy. Number of Muslim mosques and hundreds of houses and business places of the innocent Muslims were set on fire by the Sinhala Buddhist extremists while the government and police had become mere onlookers.

At the same time the civil society too remains fragmented on ethnic, political, and social lines. Although certain civil society actors have the power to persuade political authorities collectively, they lack in mobilisation power.

Meanwhile in the North as well as the South, nationalist forces have gained strength mainly due to the Government’s inability deliver on its promises of political, social, and economic justice.

In this context, Government of Sri Lanka may not have political will and people’s mandate to implement the promises it made on promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka.

The challenges before the democratic forces in Sri Lanka today are, therefore, immense and decisive. International Community too needs to have a fresh look at the developing situation and focus the collective effort on strengthening protection of human rights, furthering reconciliation and ensuring accountability in Sri Lanka.