|

| Many of the displaced were uninformed |

The last group of over 300 people from Menik Farm, once the world’s largest camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs), have been moved out, but not to their former villages.

“The world is being told an untruth about us being resettled,” Sivaguru Angaramuttu Udalayakumari, a 43-year-old IDP relocated from Menik Farm, told IRIN as she got on a bus, adding that she had little idea where she was going.

The group was not allowed to return to their homes in the Kepapilavu area of northeastern Sri Lanka’s Mullaitivu District because their land was being occupied by the military,

but were instead, relocated on state-owned land and must wait to hear if they will be able to return home or, if not, whether they will receive compensation, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) reported.

Menik Farm closed officially on 25 September amid protests by 346 IDPs from the village of Kepapilavu who claimed they were being relocated against their will.

Following the end of Sri Lanka’s decades-long civil war, more than 225,000 Tamil IDPs lived in the camp at its peak, where they received international and government assistance, including shelter, food, water, education and health care.

On 24 September, Security Forces Commander Maj-Gen Boniface Perera said the last group of 1,186 IDPs from the war would be resettled in their villages in Mullaitivu.

However, according to the 346 displaced from Kepapilavu, that did not happen. Many say they cannot return to their homes because their land has been taken over by the military.

“When officials arrived on Tuesday [25 September], people started weeping and asking why they were being brought to Seeniyamottai when their homes were in Kepapilavu,” Udalayakumari said.

Government provides tents, shelters

Initially brought to a school in Vattrapplai in Mullaitivu, the IDPs were later brought to a recently cleared jungle area near the village of Seeniyamottai in Mullaitivu where they were given tents and food rations by the government.

A limited number of transitional shelters had already been constructed.

“An army officer instructed us to move out of the school [in Vattrapplai, Mullaitivu District, where they were allowed to stay one night before being relocated]. We thought we were being returned home, but we have been relocated without any assurances of being resettled in our village,” Udalayakumari said.

Photo: Contributor/IRIN |

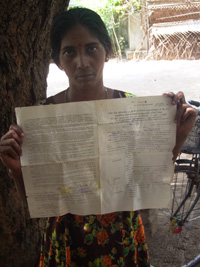

| Manoharan Suriyakumari has a deed, but no house |

As of 28 September, access to the Kepapilavu IDPs remains limited, with nobody other than family members of the displaced allowed into the area, which has a strong military cordon.

“Some people are here with the clothes they wear and little else,” said Udayakumari, who also complained of the lack of facilities. “We have just been brought here. There are no facilities in this cattle shed.”

Manoharan Suriyakumari left Menik Farm in 2010 to live with a host family in Seeniyamottai. Despite having a clear title deed to her property, she too is unable to return to her home which is a only few metres from where she now stays. “My plight is common to many. Our homes and lands are occupied by the military and we have never been compensated. There are no signs of them leaving or of restitution. This is why we are not being resettled,” said the 41-year-old.

Whether this final batch of IDPs will one day be allowed to return to their homes remains to be seen. However, the prognosis does not look good.

“This is a permanent facility. It is not possible to facilitate their return to the place of origin,” Nagalingam Vedanayagan, the government agent for Mullaitivu told IRIN on 28 September. “An army camp still exists there and we cannot say when the properties can be released. Instead, lands will be provided in Seeniyamottai for these IDPs and their construction of homes will be facilitated by the government.”

UN concerns

On 25 September the UN welcomed the closure of Menik Farm, but expressed concern over the plight of those unable to return to homes now occupied by the military.

“The government is looking for solutions, but it is important that the displaced people should be able to make an informed and voluntary decision about their future, including being part of the planning and management of their resettlement,” said Subinay Nandy, the UN humanitarian coordinator in Sri Lanka.

Nandy called on Colombo to fully implement the recommendations of the government’s Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LRRC) concerning the rights of people displaced by conflict.

“Allowing people to settle anywhere in the country and resolving legal ownership of land for those who have resettled away from their original homes is a key part of the reconciliation process.”

Photo: Contributor/IRIN