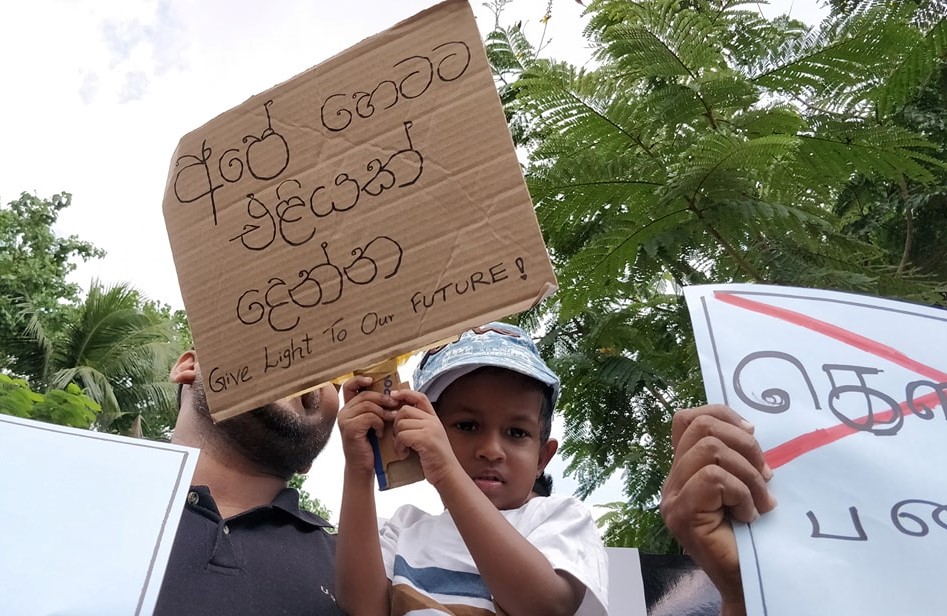

Image from Social Media.

Heralding youth as catalyst for change is not a new phenomenon be it globally or in Sri Lanka. While it is perhaps one of the most overused phrases in history it does warrant merit, as the adage goes there’s no smoke without fire. Nevertheless, the connotation of youth for change in Sri Lanka may not always invoke pleasant memories, in fact youth insurrections ran the streets red with blood in 70’s and 80’s. Nonetheless, Youth without any political, ethnic or association of creed are heralded as the prospect of a better future for Sri Lanka. Globally, youth have been involved in bettering lives of many in local, national and international fronts. In Namibia youth are critical in the promotion of drip irrigation to reach the Sustainable Development Goal of Zero Hunger. Two sisters from Indonesia (in Bali) pioneered the global movement of “Bye Bye Plastic Bags”, now commands an international audience to eradicate the use of plastics and brings together youth to systemically address issues stemming from plastics in the ocean. Sri Lankans Anoka Primrose Abeyrathne (conservationist, social entrepreneurship pioneer) and Jayathma Wickramanayake (UN Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth), among others, too champion the cause of bettering the lives of people in global and local arenas. Yet even-as the space for participation and the recognition of youth as key political and social stakeholders expand globally, the degree to which youth can affect national level policy making on national level issues remain, at best, limited. There are myriad of reasons for this issue, a few of these include:

-

Lack of systematic means for Youth consultations in policy-making

-

Waning awareness on national issues owing to:

-

Lack of political socialization via the national education system

-

Disillusioned in existing state and non-state processes for participation

-

Lack of appropriate representation

-

-

Marginalization of youth sentiments and expressions.

However, this commentary is not to serve as a discussion of remedial measures for the aforementioned and other issues pertaining to participation of youth but rather as a highlight of the NEED for youth participation, in this case in Transitional justice.

Transitional Justice is a process focusing on dealing with the past or addressing widespread violations of human rights and the recognition for victims and promotion of possibilities for peace, reconciliation and democracy. This is achieved through its pillars i.e. seeking the truth, providing reparations, providing accountability and ensuring guarantees of non-recurrence. In Sri Lanka the current architecture for such an agenda has been set by the Consultation Task Force Report, the United Nations Human Rights Council Resolution 30-1, Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, Paranagama and Udalagama Commissions and other commissions under the Bandaranaike-Kumaratunga and Premadasa regimes. Their aim, broadly speaking, sat with providing measures for the state to addresses structural, societal and cultural aspects that led to repeated cycles of violence in the nation. Thus, then we must understand why youth are critical for this process.

-

Youth as advocates for youth concerns

Youth in Sri Lanka have been victims of violations either being subject to violence during conflict. However, the pedestal to address concerns facing youth victims, i.e. reintegration into society, psychosocial support, providing for education and vocational development has largely been left as a state exercise or has found itself under development agendas of state and non-state entities. The rights violations of youth victims are generalized into the age-old dogmas or catechisms of unemployment, narcotic abuse and general disenchantment with society as a whole. Perhaps only the Special Presidential Commission of Inquiry into Youth Unrest and Rebellion (1991) took this a step further in understanding the mindset of and issues pertinent to youth however their recommendations were met with limited implementation.

Therein lies the need for Youth to seize the platform in articulating their own concerns as well as of their peers for it is youth who knows their mindset better than others, and it is Youth that must highlight and provide solutions for their own issues and such is the case also for transitional justice.

-

Mobilization of Youth

Unlike the 70’s, 80’s or even the 90’s technology has provided multiple avenues for youth to mobilize themselves, to make their voices heard or in a literal sense their text to be seen. Within the transitional justice sphere in the nation it becomes critical for youth to examine how best they can facilitate the work of transitional justice measures but moreover, how best to ensure that they increasingly participate in mechanisms of truth, justice and reparations to ensure that their narrative is included in how the past, and its impacts, are remembered by society-at-large. Mobilization need not be in terms in a traditional sense of formalized groups, although in the opinion of this author it maybe far more effective, it could be of informal groups, singular entities or individuals that possess a permanent moral centre akin to a movement i.e. such as Metoo or Occupy Wall Street where the moral edifice of the movement is built collectively but every individual can claim ownership of it.

-

Demand the creation of CONSULTATION frameworks within Transitional Justice Mechanisms

While policy making is a cumbersome exercise, it bodes well for Youth to demand that policy making takes into account their views and perspectives when making policy, the question then is HOW is one to do that? One outlook that should take place in the construct of the state is to include a policy feedback/input mechanism vested under the National Youth Services Council or even the Parliament of Sri Lanka for youth to provide input into the policy agenda of the country. Similarly, transitional justice measures where feasible must accommodate the views of youth in implementing their respective mandates. For example, it would bode well for the Office of Reparations to establish a permanent mechanism, in central and peripheral areas, to provide input in guiding its formulation of reparations policies as well as obtain feedback on how targeted policies, hopefully, enacted by the office is performing in relation to youth issues.

-

Championing non-recurrence and guardians of tomorrow

Youth has an important role to ensure non-recurrence of conflict in our nation, albeit one that maybe interpreted as self-serving. Youth have the MOST to lose in case of resurgence of violence in whatever scale and form. It is the youth that engage in processes to quell war, it will be youth that will suffer the brunt of the societal rifts and social effects conflict will leave and will feel the economic ramifications of the violence in the years to come and it is also YOUTH of today that will have to shoulder the primary blame for conflicts of tomorrow. While YOUTH may not need to take to the streets, Youth must focus on supporting the causes of victims of conflicts irrelevant of geographic and demographic divides of the country. In addition, as the most vocal segment in society on the need to challenge the norm and demand reform, youth are ideally placed to ask and put into effect for better systems for governance, addressing grievances, quelling impunity and supporting inclusive policies.

Youth must assume their rightful place as positive agents of change while it is a position that is thrust upon them, YOUTH must sculpt the contours of what society will look like tomorrow according to ideal norms of what an inclusive society should be today and tomorrow.