By S W R de A Samarasinghe.

Last Saturday’s Local Government (LG) Election dealt a stunning blow to President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and the two respective political parties, UPFA and UNP, that they lead and paved the way for the major political comeback of former president Mahinda Rajapaksa.

The Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) that Mahinda Rajapaksa leads literally swept the polls conducted to elect members for 341 LG bodies. At the time of this writing (all data in this article cover over 90% of the poll and it is unlikely that the balance results would change the substance of the analysis) the party had won about 75% of the 304 LG bodies for which results had been declared.

Voting Pattern

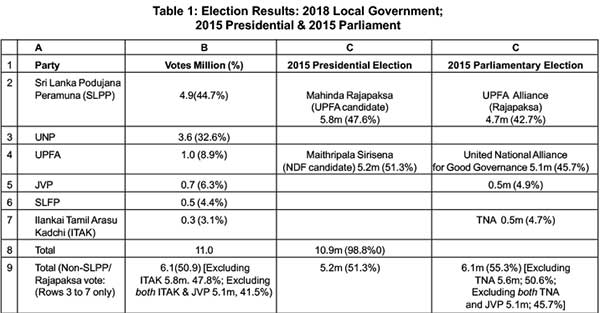

However, the results can also be described as one that has numbers without much of a difference when compared with the presidential and parliamentary polls of 2015. On Saturday the SLPP polled 44.7% of the total poll (see Table 1). The percentage will be slightly higher if the votes of the few Independent Groups that stood for the SLPP are added. In the 2015 presidential election, Rajapaksa polled 47.6% and in the 2015 parliamentary election his party, UPFA, polled 42.7%. In very general terms Rajapaksa and his party has had the support of around 45% of the electorate in the three polls. The most notable revelation is that he has a solid base of over 40% that his rivals do not have.

The non-SLPP vote has also not shown much movement. On Saturday its vote share was around 51.3%. In 2015 Maithripala Sirisena polled 51.3% in the January presidential election. In the August parliamentary election the non-Rajapaksa vote including that of the TNA was 55.3%.

Table 1: Election Results:

2018 Local Government; 2015 Presidential & 2015 Parliament.

[Excluding TNA 5.6m; 50.6%; Excluding both TNA and JVP 5.1m; 45.7%]

Sources: 2018 from media outlets; 2015 from the Department of Elections.

However, if both the TNA share as well as the JVP share are excluded from the Saturday vote the combined UNP-UPFA-SLFP share falls to 41.5% from the 45.7% that the same party combination polled in the August 2015 parliamentary elections. This is a serious loss of 4.2 percentage points. Some people not voting on Saturday as a mark of protest against the government that failed to fulfill its promises and some switching the vote to the JVP or the SLPP are the likely reasons for this. There is a two percentage point uptick in the share of the SLPP vote compared to the share in August 2015. These movements are sufficient to make a difference to the result when an election is close.

These numbers do not imply that if the UPFA and UNP would have done any better if they had contested under one ticket. First, the proportional allocation of 40% of the seats under the Additional List compensated the UPFA even if it failed to win ward seats. Second, such an alliance may have even polled less because Sirisena’s UPFA gave some the opportunity to cast a protest vote against the UNP without feeling that they were completely undermining the Yahapalanaya admistration.

Rajapaksa Comeback

The electoral upheaval on Saturday can be explained as follows.

First, Rajapaksa’s base vote in the electorate has held up very well over the past three years. He has succeeded in making a local government election a referendum on the government and has re-emerged as a, if not the most, formidable player in Sri Lankan electoral politics just three years after his ouster from power. The UNP General Secretary Kabir Hashim in a post election communiqué has admitted that the result is a reflection of the failure on the part of the government to meet the expectations of the voter.

Second, the SLPP did best in the predominantly Sinhalese-Buddhist districts and especially in the rural areas in those and other districts outside the north and east. For example, the districts of Hambantota, Moneragala, Matara, Ratnapura and Galle that Rajapaksa’s UPFA carried by more than 55% in the 2015 presidential election and by more than 50% in the 2015 parliamentary election voted overwhelmingly for SLPP last Saturday.

In contrast the UNP did better in the urban areas, and especially in the ethnically mixed areas. For example, UNP won the Kalutara Urban Council and Galle Municipal Council in the respective districts but did poorly elsewhere. The Colombo Municipal Council that has around 400,000 voters of whom about 60% belong to ethnic minorities, voted 46% UNP and 21% SLPP. This voting pattern is in consonance with the widely held view, rightly or wrongly, that Rajapaksa stands for a more Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalist Sri Lanka and the UNP stands for a more cosmopolitan and ethnically inclusive liberal Sri Lanka. Identity politics still matter in Sri Lanka’s electoral politics, both in the south and north.

Future

It is common to exaggerate the importance of current events and change. Thus, terms such as “crisis, watershed” and “end-of-the road” will be used when evaluating last Saturday’s election results and their implication in the near and medium term. With the passage of time this may turn out to be just another of those many “historic” elections that we have had in the past. Having said that, it is useful to ask the likely challenges that the main political actors, parties, groups, and more generally, the country will have to have to face, especially in the coming weeks and months.

Mahinda Rajapaksa and his party obviously have cause for great satisfaction and celebration. Rajapaksa and the SLPP are likely to attract politicians including some current MPs and ministers who may see a brighter future for themselves by throwing their lot with the SLPP. The party will also use its newfound local government base to prepare for provincial and national electoral battles that are coming up in the next two to three years. In particular the strategy of relentless criticism of the present administration that yielded significant electoral dividends for the SLPP are likely to be pursued with even greater vigor.

President Sirisena is bound to be deeply disappointed that he and his UPFA do not have a significant political base in the country. In theory he has several choices. The first and easiest is to complete his current term and retire. Reaching an understanding with Rajapaksa and the SLPP to reunite the old SLFP is another option. The third is to continue the Yahapalanaya coalition but with some significant reform aimed at winning back public confidence that he, Wickramasinghe and the UNP have forfeited to some extent.

UNP

Ranil and the UNP have to face their own set of challenges. The loss of Wickremesinghe’s “Mr. Clean” image contributed to the election debacle. It can be argued that his government actually made a major contribution to the cause of good governance in this country by allowing an independent commission to probe and issue a report on the Central Bank bond scandal that has implicated several top men in the government. But in the eyes of the average voter that is unlikely to fully redeem Wickremesinghe and others who have been implicated. In fact the opposite happened in the election campaign when SLPP speakers argued that allegations of corruption against its leadership remained unproven whereas those against the UNP have been formally proven.

Reform

[alert type=”success or warning or info or danger”]Notwithstanding the above complication, Wickremesinghe and the UNP may be able to reach an agreement with Sirisena to go for policy reform. Such a fresh strategy may include a more sincere effort to have good governance, do some development work that have an appreciable and quick impact on the lives of the people and, take steps to avoid the looming economic crisis that may occur if the government fails to abide by the IMF Extended Fund Facility Agreement signed in June 2016 for three years to get assistance worth $1.5 billion. In addition, for good measure, the government could make a serious bid to investigate the wrong doings and corruption of any and all irrespective who they are or were. But this may be wishful thinking in the Sri Lankan context.[/alert]

Leadership Vacuum

Sri Lankan political leaders typically do not allow other members of their own party to come up to senior leadership positions with prospects of succeeding the leader unless they are family members. The rare exception was J R Jayewardene. In the current political scene grooming of family members is very evident in the SLPP. In the UNP Wickremesinghe is not grooming any family members. But neither has he permitted any potential challengers to gain much prominence.

The country is hungry for efficient and honest leadership. From the country’s perspective though not necessarily from the UNP’s or UPFA’s, one passible option is a radical realignment of political forces in the south under a “new” and a semi formal “collective” leadership of sorts that includes Sirisena and men like Karu Jayasuriya and Sajith Premadasa and a few others drawn from any quarter who have broad appeal to different segments of the electorate; Sinhala-Buddhist majority, ethnic and religious minorities, urban and rural dwellers, and the professional class. But such a realignment may be the ultimate in wishful thinking.

First published in The Island.