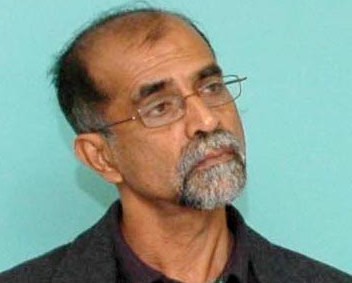

In this insightful interview with the Sunday Observer, Prof. Jayadeva Uyangoda, a veteran political analyst shares his extensive knowledge on the evolving political landscape in Sri Lanka. With a focus on the recent Presidential election and its implications on governance and reform, Prof. Uyangoda discusses the significant shifts in political power, the pressing need for structural changes and the impact of political clientelism on good governance. He also examines the challenges faced by the newly elected National People’s Power (NPP) Government and emphasised the essential steps required to address the socio-economic grievances of the population. In his analysis, Prof. Uyangoda offers valuable perspectives on the future of Sri Lanka’s democracy and the path towards a more equitable political system.

Q: The recently concluded Presidential election can be seen as a reflection of the frustration and rejection by the people of the country of 76-years of a corrupt bureaucratic system which had been partly responsible for creating such a monster. In an internationally published article, you identified this political change as the outcome of the Aragalaya. How do you understand this remarkable regime change?

The crisis exploded in 2021 and 2022 which had been building for several decades. As you said, the Aragalaya in 2022 was primarily a response to the economic collapse and the social discontent that became evident in the past two years, particularly after the IMF reforms undertaken by Ranil Wickremesinghe’s Government to address the debt crisis. This is why society needed radical transformation in politics and the NPP provided a voice for that. There was a call for corruption-free governance, accountability from rulers and an end to nepotism and the concentration of political power among elite families.

The broadening of the democratic foundations of governance became a popular demand. The demands articulated during the Aragalaya were powerful, emphasising the need for ‘system change’. However, it is crucial to note that the Aragalaya did not ultimately lead to a regime change.

A: Exactly. There was no other political party or organisation at that time. In 2022, the NPP was not in a position to make a significant intervention. However, later on, I believe the space opened for them to emerge as a credible ruling party. This process began in 2022 and the Local Government election campaign in 2023 was quite effective. The Government did not want to hold the Local Government elections due to the rising support for the NPP, which is very interesting.

Soon after the suppression of the Aragalaya, the NPP emerged as a powerful alternate political force. The cancellation of the Local Government elections did not negatively impact their emergence. At the same time, the SJB (Samagi Jana Balawegaya) emerged in 2020 as the main Opposition party and consolidated its position effectively, displacing both the UNP (United National Party) and the SLPP (Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna).

In September this year, we are witnessing a remarkable transformation in the political party system in Sri Lanka. The traditional ruling parties have been reduced to smaller parliamentary parties. Two new entities, the NPP and the SJB, have emerged as the dominant parties marking a significant shift in the political landscape.

If we look at the current state of the UNP, SLPP and SLFP, we see that they are in total disarray and fragmented internally.

A: At present, there is a vacancy for a right-wing political party due to the collapse of the traditional right-wing. The UNP represents the Colombo elite society, which includes the upper class and upper castes but there are also other caste groups involved. This fusion of caste and class represents a small minority of the population. However, parliamentary democracy and universal franchise have enabled them to emerge as a mass party and that was the UNP. It has historically been a party of the elite.

Even now, you can see that the UNP consists of a collection of individuals with a mass following. However, the UNP once had a strong electoral base and competed with the SLFP (Sri Lanka Freedom Party), which was formed in 1952 as a breakaway party from the UNP. There was intense competition between the SLFP and the UNP for the same electoral base, primarily among the rural poor and to some extent, the urban poor. J.R. Jayewardene played a crucial role in strengthening the mass base of the UNP at the expense of the SLFP in 1977. Later, Ranasinghe Premadasa successfully re-consolidated the UNP’s electoral base but his death marked an important transformation within the party.

The UNP’s mass base has remained largely among the poor but the Colombo-based elite regained control of the party. Under Ranil Wickremesinghe, however, the UNP suffered a major setback because he never attempted to consolidate the rural and mass base of the party. As a result, the UNP became a party without a mass support base. Realisation should have dawned on Ranil Wickremesinghe with the defeat of the UNP in the 2020 parliamentary election that the party needed to rebuild its mass electoral base, which he did not do. Even after becoming President in 2022, he took no action to restore the UNP’s foundational support.

Looking ahead to the 2024 elections, we can see that both the SJB and NPP are competing for the support of the mass electorate that the UNP, SLFP and SLPP previously enjoyed. Most of the poorer social classes and middle classes have left these traditional parties. This transformation is a fascinating process. The shift in social bases of political power has been rapid since the 2020-2021 period, which explains the emergence of the SJB and the NPP as the two main political parties. I believe this trend will be confirmed in the upcoming parliamentary elections as well.

Q: President Anura Kumara Dissanayake is a people’s President and can also be understood as a populist leader. We have had very bad experiences with populist leaders and it seems that only a populist can gain power in this part of the world. However, there is hope for this President due to his Marxist outlook and his party’s Marxist leadership. How can he balance these two extremes?

A: The term ‘populist’ often carries a negative connotation, which can obscure our understanding of the situation. The Sri Lankan political landscape has changed dramatically. Voters now hold a flexible relationship with political parties, as demonstrated by the mass shift in support from the SLFP and UNP to the SLPP in 2020 and later to the NPP in 2024.

President Dissanayake appears aware of this need, emphasising it in his acceptance speech and considering negotiations with the IMF for a more substantial program. However, if he fails to deliver relief, disengagement from previously supportive voters will likely occur, giving opposition parties the opportunity to exploit the situation.

On a more positive note, there seems to be a renewed wave of support for the NPP, and I believe they could secure a parliamentary majority. Addressing the economic grievances of the population will be a significant challenge and should become a top priority for the Government, reflecting a stark contrast to the previous administration’s approach.

A: People will have patience. There has been no violence and protests have not been violent. However, this patience should not be mistaken for disinterest. While people are patient, the Government must implement pro-poor policies, including effective economic and taxation strategies that do not burden the poor and middle classes further.

As a result, ordinary people have expressed that they are doubly victimised — first of the crisis itself and now of the Government’s policies aimed at overcoming it. In response, a new slogan has emerged in Sri Lankan politics: ‘Economic Justice’. The NPP has wisely incorporated this term into their policy statements.

People are demanding that the burden of the economic crisis be shared fairly among different social classes. Currently, middle-class citizens, the poor and public servants are disproportionately shouldering this burden. Therefore, the Government must formulate policies that address these economic and social grievances effectively.

Q: It is evident that the entire political culture is based on political clientelism, which has emerged as a significant factor hindering good governance. The One Text Initiative (OTI) recently launched the book titled ‘Political Clientelism in Sri Lanka: A Snapshot’, highlighting the obstacles to good governance. This culture is particularly pronounced in this region, which is intertwined with underdevelopment and cultural backwardness. How do you understand this issue and how can we address it?

A: Eliminating political clientelism is difficult. We must first recognise that this crisis exists. That is why the NPP’s policy statement emphasises the need for a new political culture, a sentiment that was also a key slogan during the Aragalaya Movement. The public is quite aware that the political culture needs to change with clientelism being one major aspect.

What is needed is significant political will. Hopefully, the NPP Government will have this political will, as they are not dependent on the clientelist networks that other parties rely on. This independence gives them the capacity to enact meaningful change.

However, we must also recognise that if the Government tries to consolidate clientelism, it may create a new political class that perpetuates the same problems. The President needs to understand that eliminating bribery and corruption will likely provoke reactions from those who benefit from the existing clientelist system. Addressing this issue requires careful management and a commitment to genuine reform.

Q:In the Nomination Lists of all parties for the upcoming General Election, it is evident that there will be a significant change in the new Parliament, which is set to commence on November 21, featuring fresh faces in both the Government and the Opposition. This shift aligns with one of the main slogans of the Aragalaya movement, where people protested with the message ‘No to 225’. However, on social media, it is widely acknowledged that the NPP Government may consist of a number of inexperienced lawmakers, which could cause unrest in the bureaucratic system during the initial stages. How do you think the Government will be able to balance this without creating a major stress in the process?

Traditionally, in a parliamentary system, even inexperienced politicians have relied on an experienced bureaucracy. However, in Sri Lanka, the bureaucracy has endured significant political control by Ministers and Presidents, undermining the strength of the civil service.

Since the 1972 Constitution brought public service under direct political leadership, the independent nature of the public service has declined. That said, there are still many capable public servants, including retired professionals who can contribute positively.

My sense is that the NPP has already identified qualified individuals for key positions. They have access to a pool of senior retired public servants who support their commitment to corruption-free governance and effective administration. This situation presents a unique challenge for the NPP Government — essentially an experiment in governance with political leadership lacking a strong background in Cabinet or parliamentary systems, compounded by a weakened bureaucracy due to the presidential system and political interference.

Navigating this complex landscape will be a considerable challenge for the NPP Government, but it also provides an opportunity for reform and innovation in governance.

A: Scrapping the Executive Presidency requires a two-thirds majority in Parliament and a referendum. It is important to eliminate this system, as it has caused significant damage to society and politics. This was a key promise made in previous election mandates, and many people support this idea.

If the Executive Presidency is removed, the Prime Minister would become the centre of political power and be accountable to Parliament, leading to a system of checks and balances. However, I believe that simply returning to a parliamentary system will not be sufficient.

We need a Cabinet Government where the Prime Minister is elected and held accountable to Parliament, with strong checks and balances in place to prevent the abuse of power. A Prime Ministerial Government can be just as problematic as an Executive Presidency if these safeguards are not established.