Image: The Special Rapporteur regrets the insufficient progress made regarding truth-seeking in Sri Lanka.

In the follow-up on the visit to Sri Lanka Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence, Fabián Salvioli says that “over the past 18 months, the human rights situation in Sri Lanka has seen a marked deterioration that is not conducive to advancing the country’s transitional justice process and may in fact threaten it. The Special Rapporteur deeply regrets the insufficient implementation of the recommendations made by his predecessor and the blatant regression in the areas of accountability, memorialization and guarantees of non-recurrence and the insufficient progress made regarding truth-seeking.”

This report will be presented to the upcoming 48 session of the UNHRC for a interactive dialogue.

Sri Lanka Section of the report fellows:

IV. Follow-up on the visit to Sri Lanka

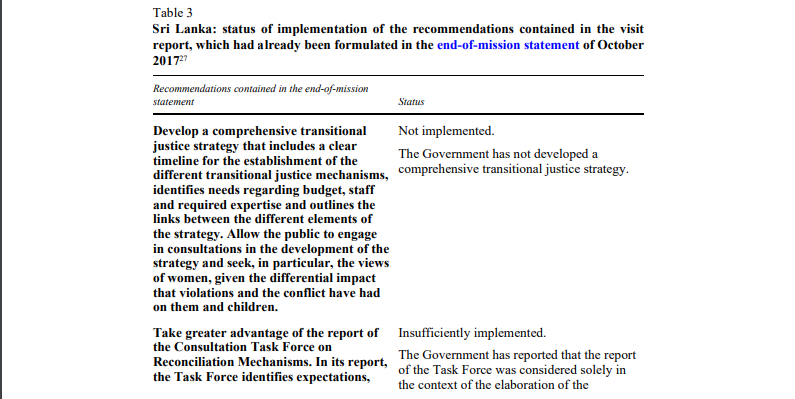

24. The former Special Rapporteur visited Sri Lanka from 10 to 23 October 2017 at the invitation of the Government. He presented his end-of-mission statement with preliminary findings and recommendations on the visit in November 2017 and presented his final report to the Human Rights Council in September 2020.16 The present report contains an assessment of the status of implementation of the recommendations made in the country visit report, which had already been formulated in the end-of-mission statement of October 2017.17 This is to ensure sufficient time has been allowed for their implementation.

25. The Special Rapporteur regrets that no submission for the present report was received from the Government of Sri Lanka. Comments to the present report were received on 9 July 2021.

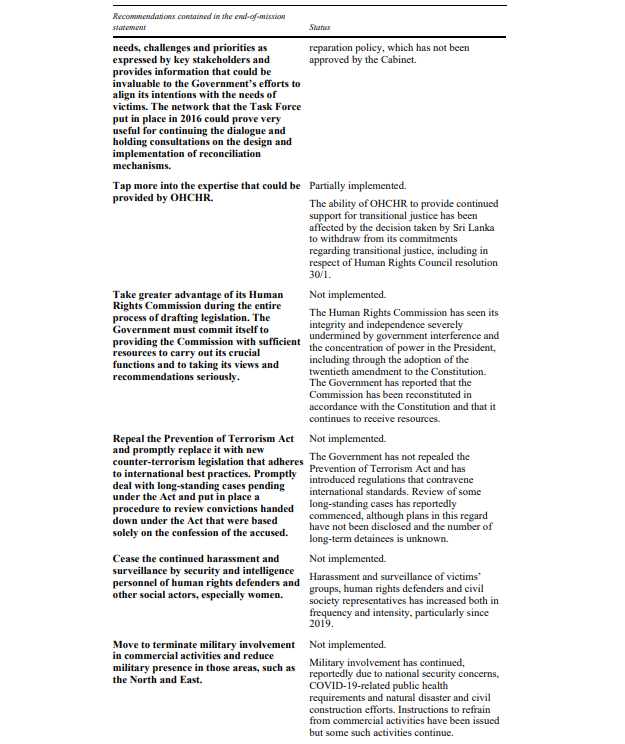

26. The commitments made by the administration led by President Maithripala Sirisena to undertake constitutional reforms, strengthen oversight bodies, curb corruption and engage with the international community to provide accountability for past abuses, including through implementation of Human Rights Council resolution 30/1, took an abrupt turn with the presidential elections in November 2019. The new administration, led by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, proceeded to withdraw Sri Lanka from its international commitments regarding transitional justice, including in respect of resolution 30/1. This political shift has translated into a slowdown in the transitional justice agenda and a reversal of some of the progress made during the previous administration.18

27. Concerning accountability for past human rights violations, the Special Rapporteur regrets the lack of substantive progress in the investigation of emblematic cases, despite initial progress. Under the previous administration, the Criminal Investigation Department had made progress in investigating some violations, enabling some indictments and arrests; the High Court Trial-at-Bar held a hearing in the case of disappeared journalist Prageeth Eknaligoda; a High Court at Bar was appointed for the Weliveriya case; the Attorney General reopened investigations into the 2006 killing of Tamil students in Trincomalee; and indictments were served against suspects in the murder of 27 inmates at the Welikada Prison and against suspects in the 2013 Rathupaswela killings.

28. However, progress on several emblematic cases has stalled or encountered serious setbacks under the current administration. Investigations into military and security officers allegedly linked to serious human rights violations have in several instances been suspended. In some cases, the alleged perpetrators have been promoted despite the allegations against them. The commission of inquiry to investigate allegations of political victimization of public servants established by the current President has intervened in favour of military intelligence officers in ongoing judicial proceedings, including in the 2008 murder of journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge and the 2010 enforced disappearance of Prageeth Eknaligoda. It has also issued directives to the Attorney General to halt the prosecution of former Navy Commander Admiral Wasantha Karannagoda and former Navy Spokesman Commodore D.K.P. Dassanayake in relation to the killing of 11 youths by Navy officers, which have been rejected by the Attorney General.19 The Court of Appeal also issued an interim injunction order staying the case, following a writ submitted by Mr. Karannagoda. The case is due to be heard by that Court. The above-mentioned commission of inquiry has also interfered in other criminal trials, including by withholding documentary evidence, threatening prosecutors with legal action and running parallel and contradictory examinations of individuals already appearing before trial courts. In April 2021, the Prime Minister tabled a resolution seeking legislative approval to implement the recommendations of the commission of inquiry to institute criminal proceedings against investigators, lawyers, witnesses and others involved in some emblematic cases and to dismiss several cases currently pending in court. A special Presidential commission of inquiry composed of three sitting judges is to decide on the commission’s recommendations.

29. Efforts to ensure accountability have been further obstructed by reported reprisals against several members of the Criminal Investigation Department involved in the past in investigations into a number of high-profile killings, enforced disappearances and corruption.20 Some have been arrested and later released on bail, and another has left the country.

30. The current administration has shown that it is unwilling or unable to make progress in the effective investigation, prosecution and sanctioning of serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law, which deeply worries the Special Rapporteur. In this context, he welcomes the adoption in March 2021 of Human Rights Council resolution 46/1, by which the Council decided to strengthen the capacity of OHCHR to collect and preserve evidence for future accountability processes for gross violations of human rights or serious violations of international humanitarian law in Sri Lanka and present recommendations to the international community on how justice and accountability can be delivered. The adoption of the resolution was opposed by the delegation of Sri Lanka, which cited ongoing domestic remedies and independent processes.

31. The Special Rapporteur regrets that no truth commission has been established to date. Such a mechanism would be of considerable value in helping Sri Lanka to understand the root causes of the conflict and open a common public platform for all communities to share their lived experience.

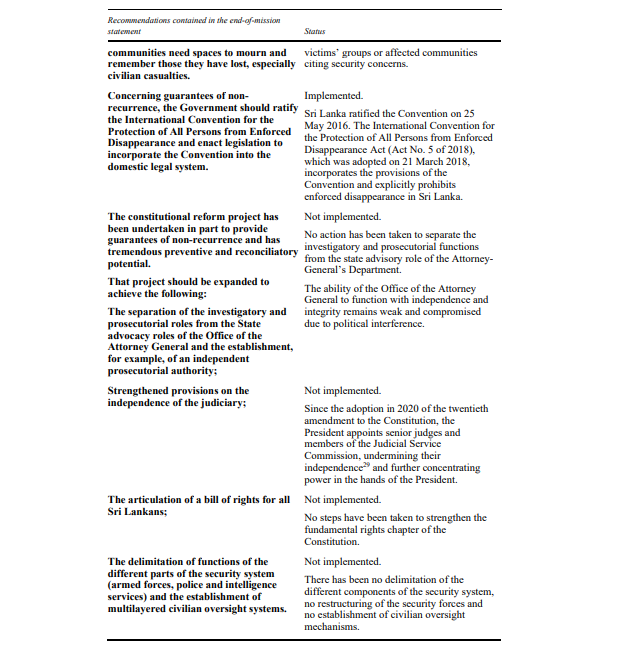

32. During the period 2015–2019, progress was reported in the work of the Office on Missing Persons, which opened four regional offices in Batticaloa, Jaffna, Matara and Mannar covering also adjoining districts, adopted a psychosocial support strategy for families of disappeared persons in consultation with victims and other stakeholders and participated in forensics and archiving training. However, since 2020 progress has stalled and the Office has faced interference from the Government, which reportedly intends to review the law establishing and defining the mandate of the Office and which has appointed the former Chair of the commission of inquiry to investigate allegations of political victimization, Upali Abeyrathne, to head the Office. As the original set of commissioners ended their mandate in February 2021, there is considerable concern that this and other new proposed appointments will seriously undermine the independence and credibility of the institution, eroding victims’ trust in it and weakening the Office’s ability to discharge its mandate effectively.21 The Government has reported that the commissioners have been appointed following constitutional procedures.

33. The Special Rapporteur urges the Government to maintain its support for the Office on Missing Persons, including by providing it with sufficient resources and technical means, and to guarantee its independence and effective functioning.

34. The Special Rapporteur is concerned about the several instances since November 2019 in which government authorities have tried, through judicial action, to suppress memorialization efforts by families of victims and conflict-affected communities, citing security as well as COVID-19-related public health risks.22

35. The harassment, threats, surveillance and obstruction of activities of victims and human rights defenders has reportedly increased both in frequency and intensity in 2020, which the Government justifies as related to security concerns. In one reported case of reprisal, representatives of families of the disappeared in the North-East who attended Human Rights Council sessions in 2018 and 2019 were subjected to surveillance, harassment and intimidation upon their return to Sri Lanka. Families of the disappeared and witnesses to human rights violations have reportedly been harassed in similar ways.23

36. In July 2019, the Office on Missing Persons issued a protection strategy and established a dedicated unit for victim and witness protection that has developed procedures for the documentation of protection concerns and has reportedly intervened in relation to attacks against family members and other stakeholders involved in court proceedings in disappearances cases. The Government must ensure that victims, witnesses and human rights defenders are able to carry out their invaluable work in safety and without fear of reprisal. The Special Rapporteur reiterates his call for victims, witnesses and human rights defenders to be better protected as a key component of the transitional justice process in Sri Lanka.

37. With respect to guarantees of non-recurrence, on 22 October 2020 Parliament adopted the twentieth amendment to the Constitution introducing fundamental changes in the relationships and balance of power between the different branches of government. The amendment, which the Government argues was adopted following constitutional procedures, has strengthened the power of the President and the executive, effectively reversing many of the democratic gains introduced by the nineteenth amendment, adopted in 2015. It has also significantly weakened the independence of several key institutions, including the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka and the National Police Commission (whose Chairs can now be appointed and dismissed by the President), as well as the judiciary (senior judges and members of the Judicial Service Commission are now appointed by the President).24 The Government contends that institutional independence remains unchallenged despite the changes introduced by the new amendment.

38. There has also been a deepening and accelerating militarization of civilian government functions. On 29 December 2019, the Government brought 31 public entities under the oversight of the Ministry of Defence, including the police, the Secretariat for NonGovernmental Organizations, the National Media Centre and the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission. It also appointed 25 senior army officers as chief coordinating officers for maintaining COVID-19 protocols in all districts. In July 2021, the Government reported that most of the public entities that had been under the oversight of the Ministry of Defence were no longer under its purview.

39. Several special procedure mandate holders25 have strongly recommended replacing the Prevention of Terrorism Act with legislation that complies with international standards. While the previous Government had initiated alternative legislation that raised concerns from a human rights perspective26 and was later shelved, the present administration has failed to make any progress in this regard. Instead, in March 2021 the President issued a set of regulations on deradicalization and countering violent extremist religious ideology under the Prevention of Terrorism Act that allows for the arbitrary administrative detention of people for up to two years without trial. Several arbitrary arrests under the Prevention of Terrorism Act have been reported in the past year, many involving Tamils and Muslims. Furthermore, over 300 Tamil and Muslim individuals and organizations have been labelled as terrorist and included in an extraordinary issue of the official gazette. The Government has reported that it has commenced a process of reviewing some provisions of the Act and has accordingly released detainees held in extended judicial custody. The Special Rapporteur urges the Government to place an immediate moratorium on arrests under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, with a view to repealing it as a matter of priority, and undertakes prompt, effective and transparent legal review of all persons detained under the Act.

40. Sri Lanka is yet to set up a land commission to document and carry out a systematic mapping of military-occupied private and public land for effective and comprehensive restitution. The Government has reported that 89.26 per cent of State land and 92.22 per cent of private land occupied by the military has been released and that the rest will be reviewed, taking into consideration strategic military requirements. A scheme will reportedly offer compensation to holders of private land unreleased owing to national security concerns. The Special Rapporteur recalls that the mapping and restitution of land must be entrusted to an independent and impartial body.

41. Over the past 18 months, the human rights situation in Sri Lanka has seen a marked deterioration that is not conducive to advancing the country’s transitional justice process and may in fact threaten it. The Special Rapporteur deeply regrets the insufficient implementation of the recommendations made by his predecessor and the blatant regression in the areas of accountability, memorialization and guarantees of non-recurrence and the insufficient progress made regarding truth-seeking. He urges the Government to swiftly revert this trend in order to comply with its international obligations.

Sri Lanka: status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the visit

report, which had already been formulated in the end-of-mission statement of October 2017

V. Concluding remarks

42. The Special Rapporteur expresses concern about the insufficient progress in the implementation of the recommendations addressed to the reviewed States. He urges the States to accelerate implementation and recalls that many of the recommendations represent the development of treaty obligations assumed by States that require compliance.

( OHCHR)