|

| Add caption |

”Indeed, if the TNA doesn’t get its act together, put people of the North and East first, and quit bickering over powerless portfolios, then it’s is time for an alternative Tamil political party to emerge.

Tamils have been waiting long enough for a brand of politics that promotes inclusion, pragmatism and evenhandedness. They shouldn’t have to wait any longer.”

Behind The Numbers: A Closer Look At Voting Trends In Jaffna by Gibson Bateman and Rathika Innasimuttu –

Introduction

A recent article[1] has questioned our analysis[2] of the Northern Provincial Council (NPC) election results. While thoughtful, the piece – published on Colombo Telegraph – is misguided and reflects a lack of understanding of both the current political context in the north and Tamil people’s ideological mindset.

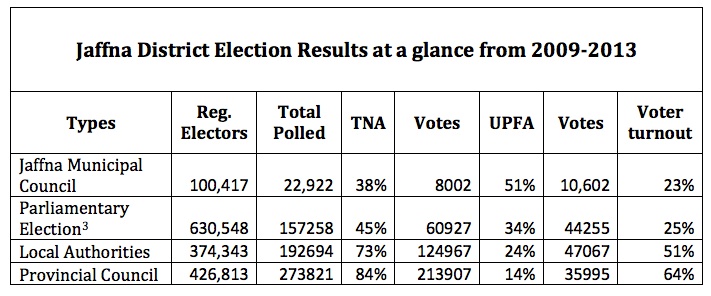

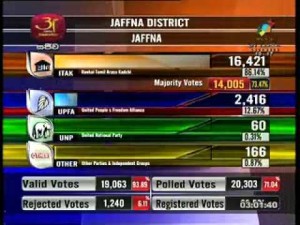

The thrust of the argument presented is that the real story behind TNA’s victory has little to do with past UPFA performance. Rather, it’s principally a product of a significant increase in voter turnout since the conclusion of war. It’s true that voter turnout has increased since Jaffna Municipal Council elections were held in 2009. But does that argument hold up under further scrutiny? Is that the main reason why TNA won last month? Or is there more nuance to this narrative than meets the eye?

Behind the Numbers

In the Jaffna Municipal Council election in 2009, 22,280 actually voted,[3] but there were only 100,417 registered voters. In the 2013 NPC election, the number of registered voters for Jaffna polling division has been listed as 28,610.[4] It is important to note here that the Jaffna Municipal Council boundary is larger than Jaffna polling division, which includes an extra nine polling sub-areas from Nallur polling division. If we do the math right, the figure for those nine polling areas can be calculated as approximately 20,454 people. [This figure is deduced by subtracting the Nallur Pradeshiya Sabha registered voters (20,012[5] people) from the registered voters of the provincial council Nallur polling division (42,466[6] people)]. This means that a more realistic number of registered voters for the Jaffna Municipal Council election would have been around 49,000. (That figure includes registered voters from Jaffna polling division (28,610), plus the approximate number of voters from nine Nallur polling stations, which amounted to 20,454 people, in 2009). This produces a much smaller pool of registered voters than official statistics suggested in 2009 – bringing the approximate voter turnout for that 2009 election to 47%. (The boundary lines for polling divisions for provincial council and local authorities elections are not exactly the same; this needs to be taken into consideration).

What’s more, the precipitous drop in registered voters from 2010 to 2011 – from 630,548 to 374,343 – is extremely curious. Where did all those people go? Why is the number of registered voters in 2011 and 2013 far fewer than in 2010? A drop of nearly 200,000 cannot go unnoticed.

One plausible scenario suggests that the number of registered voters in the Jaffna 2010 parliamentary election included scores of voters who simply were not there. Indeed, certain electoral analyses have lacked context and nuance because they omit the questions of migration, displacement, death due to war and disappearances.

Readers should also pay attention to the bulk of people – approximately 10,000 UPFA supporters – who voted for UPFA in both parliamentary and local authorities elections, yet didn’t go to the polls on the 21st of September or voted for TNA. What does that show? It reveals a clear dissatisfaction with the government and their current policies.

More on the Interpretation of the NPC Election Results

Other conclusions that some people have drawn from NPC elections are also cause for concern. While TNA has undoubtedly inspired some people to vote for it through political campaigning and messaging, it’s hard to say whether TNA’s eventual selection of Mr. Wigneswaran was perceived an example of party cohesion and unselfishness. Moreover, the recent infighting over ministerial posts and the inability of TNA’s leadership to handle that process efficiently doesn’t inspire much confidence.

Sure, the TNA was able to finally agree on Mr. Wigneswaran as Chief Ministerial candidate, but the party has been plagued by infighting for years – over a range of issues including the way decisions are made and whether TNA should register as a separate political party.

Even the eventual selection of Mr. Wigneswaran didn’t occur without several lengthy deliberations and a selection of candidates designed to appease hardcore ITAK elements, rather than on merit – which has resulted in a very difficult situation for the leadership post-election.

Besides, there was widespread speculation that Mr. Wigneswaran wouldn’t even carry the preferential vote, which would’ve further undermined his credibility within TNA. (In some of our discussions with community members, these sentiments were expressed repeatedly in Jaffna on election day). This was also concern for many youth groups, as they actively campaigned to send a pro-Wigneswaran message across on September 21st – which worked.

Let’s not forget the last days of the campaign by the TNA. We witnessed the party’s chief ministerial candidate – a person who had little patience for the LTTE throughout a celebrated legal career – venerating the LTTE’s former leader as a “great hero.” He toed the LTTE line because he had to get the highest number of preferential votes.

What was clear amongst Tamils was that they wanted to send a signal that they are united, that they have a common enemy and that that that enemy was and remains the government – an administration that is mainly interested in propagating an Extremist Sinhala Buddhist ideology to appease the Southern voters, playing the Sinhala Buddhist card to win elections and staying in power forever.

More recently, a member of TNA has reinforced these sentiments. In an interview with BBC Tamil Service, Mr. Siddharthan – who managed to get the 3rd highest number of preferential votes in Jaffna – has mentioned, “since people of the north voted against the government of Sri Lanka, many members of the TNA feel that the Chief Minister in waiting should not take oaths in front of the president.”[7]

Another argument posits that TNA’s success in the 2011 local authorities election helped facilitate an increase in voter turnout during the NPC election. It is perhaps too generous to claim that, since TNA has become more active in local governance, it’s easier for the party to get people to the polls. In fact, TNA’s participation in local governance would adversely affect its chances in forthcoming elections if local governance bodies led by TNA are widely perceived to be poorly managed and unresponsive. A recent study on local governance[8] expounds upon the prevailing sense of disappointment that community members have with their local government bodies and local elected officials.

It’s simplistic to claim that having power within Pradeshiya Sabhas, Urban Councils and Municipal Councils will inevitably lead to more political support for TNA. Indeed, as the report recently published on Groundviews notes, “local governance in the Northern province leaves much to be desired.”

Conclusion

The results of the NPC are a big defeat for GoSL and should be read as such. However, claims that – with our previous piece – we have interpreted the NPC election “solely as a referendum on the government’s post-war performance” are factually incorrect.

Rather, in our conclusion, we emphasized the following:

“The NPC election results are a big victory for TNA. However, they are also a reflection of how dissatisfied people are with the present administration’s policies – meaning that the outcome of this election is a much a referendum on UPFA as it is an outright victory for TNA.”

The broader point – that an increase in voter turnout over successive elections helped propel the TNA to victory – is well taken. Nonetheless, a closer look behind the numbers suggests that – by failing to factor in displacement, migration, death due to war and disappearances – the increase in voter turnout is not nearly as high as previously thought. From 2009 to 2013, it has increased from 47% to 64%. More importantly, an increase in voter turnout is not the principle reason behind TNA’s recent victory, not even close. What choice did Tamil people have? They didn’t want to vote for UPFA, nor do they consider UNP a viable option. Maybe if TNPF had contested things might have been little different. If EPDP had contested alone, perhaps they would have picked up a couple extra seats.

Further, while it’s true that the reasons for increased voter turnout might be “multi-layered,” the fact of the matter is that UPFA’s post-war strategy – viewing reconciliation solely through the prism of economic development and the construction of infrastructure – has antagonized the Tamil community.

In the Northern Province, the equation has changed. TNA is no longer in opposition; they are the rulers. And if they don’t perform, they could face severe consequences in forthcoming electoral bouts – just as UPFA did this time around. Solid political leadership is about sacrifice, unselfishness and putting constituents ahead of party.

Indeed, if the TNA doesn’t get its act together, put people of the North and East first, and quit bickering over powerless portfolios, then it’s is time for an alternative Tamil political party to emerge.

Tamils have been waiting long enough for a brand of politics that promotes inclusion, pragmatism and evenhandedness. They shouldn’t have to wait any longer.

*Gibson Bateman and Rathika Innasimuttu are founding members of The Social Architects (TSA). Follow TSA on Twitter @soc_arch.

[4] http://www.slelections.gov.lk/2013PPC/JAFFNA.html

[6] http://www.slelections.gov.lk/2013PPC/NALLUR.html