Over the past few months, there has been much speculation and discussion, privately and publicly, by politicians, civil society representatives, and lay people over the proposed Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

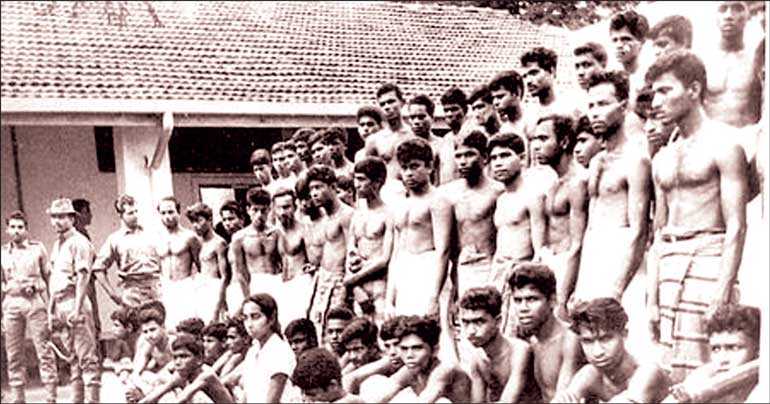

Sri Lanka has faced multiple conflicts and uprisings in its post-independence history. For more than 30 years, the country faced armed conflict in the North and East, pitting the military against the LTTE. Meanwhile, the country’s South faced violent uprisings led by the JVP.

Impunity for human rights abuses during the 1971 uprising stains Sri Lankan history. It will be difficult for Sri Lanka to move on until the government is willing to face up to this chapter in its history.

In the case of the JVP uprising, 1970 to 1980s, the Sri Lankan government did not establish a truth commission or any other mechanism to investigate the abuses that occurred during the uprising. Reconciliation for the JVP will be challenging, but it is essential for the future of Sri Lanka.

Although both conflicts were eventually crushed by the government, both left a lasting legacy of violence.

With the establishment of the TRC, there is still hope that the TRC can achieve transitional justice for the 1971, 1987- 1989 JVP uprisings and the LTTE uprising 1983-2009 if appropriately handled.

The conflicts led to allegations of human rights abuses by all parties to the conflict.

However, nearly 30 years after the end of the JVP uprising and more than 14 years after the end of the LTTE uprising, the armed conflicts in the North and the South appear to be an absence of Truth and Reconciliation.

In recent weeks, while participating as a member of the Commonwealth Observer Mission for the elections in Sierra Leone last month, I was fortunate to be able to make the most of that visit and also meet Bishop Joseph Humper, the Chairperson of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sierra Leone, and Yasmin Sherriff, the Executive Secretary of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sierra Leone. I also spoke with Justice Desmond Babatunde Edwards, the Chief Justice of Sierra Leone’s Supreme Court.

My discussions strengthened my belief that all stakeholders, including religious leaders, civil society leaders, victims, political leaders, women, and the youth, must have a say in the design of a truth, reconciliation and justice mechanism if it is to have broad acceptance and achieve its purpose. Such consultation must also necessarily focus on issues such as reparations, amnesty (if any), prosecution and other consequences for perpetrators.

Further, about the North and East, the Government has not adequately addressed issues relating to land acquisition, PTA suspects awaiting their trial for unacceptably long periods, police powers, and the prosecution of officials involved in violating rights. The meaningful resolution of these issues would also build confidence in a TRC process. A general sense that the government is committed to rights, equality, and justice and genuinely taking on board the views of victims would be paramount in securing trust and participation.

Another issue which stands as an obstacle to the process is the ongoing crackdown on peaceful protests and freedom of expression. The sincerity of a government’s exercise to achieve truth and reconciliation would be seriously questioned when its current conduct demonstrates a lack of commitment and respect for rights.

To deliver on establishing a Truth and Reconciliation Commission before any approvals are sought in parliament as an act of parliament, there must be clarity of understanding in what the TRC will be and what it can do, including mete out recommendations for justice to those affected by decades of pain and suffering and throughout the country. Establishing a truth and reconciliation commission for Sri Lanka would break the cycle of violence and impunity and promote reconciliation and forgiveness among perpetrators and victims through the entire disclosure of truth. It would also create a platform whereby the aggrieved could secure a level of justice for the harm inflicted upon them as individuals or as a collective group.

Currently, public trust in government institutions is at an all-time low. Candid conversations with people from all walks of life indicate that people have lost all trust in their government, MPs, the Ministers, and the institutions they lead. In such a background, this TRC can never be acceptable to North, East and South people. The primary focus, mainly in the North and East, is to rebuild trust and to create healing in a heavily scarred and damaged country. However, to build trust and regain, at minimum, a semblance of confidence, the working group of the TRC must consist of representatives of the victims and their families from its inception. This working group for establishing the TRC should be able to:

-

- conduct a public perception survey about this Truth Commission

- analyse risks and opportunities

- propose policy recommendations

- Seek a pathway towards healing.

To maximise the positive societal impact of this mechanism, the TRC needs to act entirely independently, free from politics, and have an inclusive and victim/survivor-centred approach.

Whilst some may feel that public dialogue will defeat the urgency of establishing and delivering the TRC, it is only through public dialogue, establishing at the front end a system of transparency, accountability, and participation, that people will feel a genuineness to what the commission promises to deliver.

Sri Lanka’s current parliamentarians, few if any, may not have experienced such suffering – may not have experienced any suffering to understand adequately. The State is also responsible and accountable for the atrocities committed during the conflicts. So, an independent committee outside Parliament must select the commission members. Only a country-specific model should be adopted.

When I visited the North as the Chairperson of the HRCSL early this year, some of the main grievances were that the breadwinners were in jail and remand. And their voices must be heard. They said that their lands still need to be returned and that they must stop being taken for various purposes unrelated to the community.

Many articulated that discriminatory security plans with strong military presence and checkpoints cause severe harassment and unfair fear psychosis. People feel deprived of their fundamental rights and relive trauma daily. The people I spoke with needed more confidence in the commissions already established for these purposes, and they saw no path to that confidence. Many people spoke of the commission’s need for foreign judges and advisors. These are just a few of the issues raised before me.

These issues need to be addressed as a pre-condition to presenting the Bill on TRC. Anything less than this will be deemed unacceptable to the people of Sri Lanka and the international community. Recently, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi has indicated how the Tamil people of Sri Lanka must be treated; this does not mean freeing a few but how its government treats many and treats all the Tamil people as citizens of Sri Lanka. The current Truth and Reconciliation Bill process is moving forward as a mere ‘box ticking’ exercise.

Before enacting a law to establish a TRC, there must be clarity among all stakeholders of what the proposed TRC is: its objectives, powers, duties and functions.

Although the President appears to have reached out to the South African model, in the South African model, the Chairman, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, was appointed by Nelson Mandela, who was a political prisoner and a member of the ANC. He felt and understood the suffering of the people during the period of the conflict.

Sri Lanka’s current parliamentarians, few if any, may not have experienced such suffering – may not have experienced any suffering to understand adequately. The State is also responsible and accountable for the atrocities committed during the conflicts. So, an independent committee outside Parliament must select the commission members. Only a country-specific model should be adopted.

The President may consider establishing a team of national and international advisers to do the front-end work and, in addition, lead the TRC as advisors.