Sri Lanka’s political landscape is distinguished by an oddity not evidenced to that unnerving extent elsewhere in this region, even with all its considerable turbulence.

This oddity is that despite an increasingly uncertain economic future as the rupee free falls to unfathomable depths and law and order falters with the Inspector General of Police (IGP) embroiled in one unseemly controversy after another, there is little unified thinking by national level politicians on how to face risks to the country’s economic and political stability which gather in ominous storm clouds above us.

From the jaundiced standpoint of citizens, what we see are quarrelling politicians who are only concerned with how to retain or usurp power while national policies from the economy to industries are left to gather dust on bureaucratic shelves. An excellent recent example is the spectacle of President Maithripala Sirisena lambasting the IGP and calling for reform of the entire police force while Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe lauds the police for ‘effective crime control.’ Meanwhile former President Mahinda Rajapaksa and his cacophonous supporters cackle with glee but offer no sensible solutions which indeed, may be somewhat vain to hope for in the first instance since it was the Rajapaksa Presidency that unprecedentedly squandered public finances for personal gain.

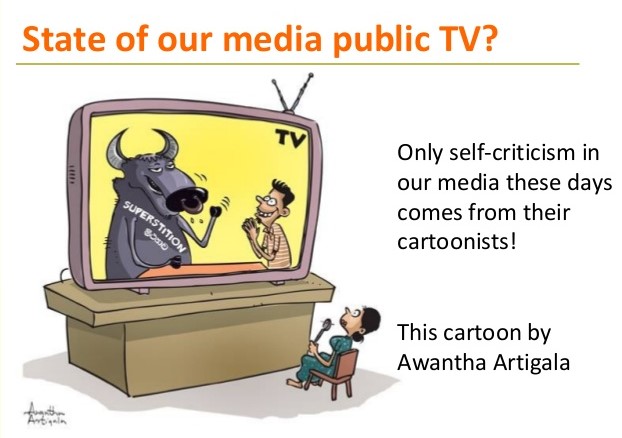

And in accordance with what appears to be the increasing madness of the political establishment, a state television channel blares triumphantly after taking television cameras to a hamlet to interview open mouthed residents, that stories saying that villagers ate ‘murunga (drumstick) leaves’ out of hunger was a ‘diabolical lie’ spun by Rajapaksa propagandists.

Acute need for independent regulation of electronic media

Indeed, it seems that state electronic media channels are rapidly reaching the asinine levels of Rajapaksa propaganda immediately leading up to the shock election defeat in January 2015. This asininity is deplorable but nevertheless, the pattern is all too familiar. In the first years of a new Government coming into power, a measure of fairness is maintained in state news broadcasts. We saw this time around as well in the months after January 2015. But as the centre of power grows uncertain, that impartiality dissolves to be replaced by blatantly partisan coverage. On its part, the private electronic media is marked by a lack of professionalism and is even more sensationalist and politically partisan in its functioning.

This is exactly why an independent broadcasting authority, exercising its neutral writ over state and private electronic media channels remains a dire necessity. Sri Lanka already has an excellent blueprint for this, laid down more than two decades ago, (in terms of the deterioration of the country’s collective intellect, it seems two eons ago) in a seminal decision of the Supreme Court in the Broadcasting Authority Bill case. Here, our best judges of the day laid down guidelines for the constitutionality of such an Authority, (Athukorale and Others v The Attorney General, 1997). It was cautioned that “having regard to the limited availability of frequencies, and taking account of the fact that only a limited number of persons can be permitted to use the frequencies, it is essential that there should be a grip on the dynamic aspects of broadcasting to prevent monopolistic domination of the field either by the government or by a few..’

It is interesting that the Court addressed its mind not only to the question of governmental control but also ‘by a few…’ in that the independence of the media is affected equally by politically biased corporates seeking to expand their sphere of influence as it is by political control. The way an Authority should operate, its composition and character was also discussed in this decision which remains a signal example of the Court taking its constitutional role seriously at the time. This is a standard that we should return to even as future priorities in media law reforms are being discussed at the national level.

Injustices that occur due to failure of Rule of Law

Meanwhile, the ‘madness of the political establishment’ has far reaching consequences. This week, a police officer, reprimanded by his superiors for stopping a lorry carrying sand without (as he alleges) adhering to the conditions of the issued permit, pointed a gun to his head in public and threatened to shoot himself. He was speedily dealt with by being clapped into prison but his relatives bemoaned the fact that corrupt superiors flout the law with impunity while subordinates implementing the law are imprisoned.

There is a point here which ought not to be missed. The police sought to justify the action taken against one of its kind by saying that a permit to operate the lorry in question had been in possession of the lorry driver and that a police officer cannot go around waving a firearm in the open. This seems eminently reasonable. However, it is less clear as to whether the conditions of the permit had been flouted.

If so, the monumental injustice meted out to this police officer illustrating the failure of the Rule of Law links up to President Maithripala Sirisena’s outburst that the entire police force must be revamped, starting from its head, the IGP. It is not a particularly reassuring sight to see Ministers shrugging off this IGP’s excesses by saying airily that this is merely due to his over-familiarity with the media. There is far more in issue here as discussed in these column spaces during the preceding weeks. And this problem must be addressed if the Government is serious about retaining public legitimacy though this tends to be in doubt given its erratic actions.

A nation perpetually in chaos

But to be clear, the reference in these column spaces to the gathering madness of the political establishment is meant equally for ruling politicians and their opponents alike. Excuses offered by Government frontliners including the Minister of Finance, citing Rajapaksa-era degradation as justification for the unsteady if not wayward stumbling of this Government is nonsensical. Even so, this is trumped by the sound and fury of the Rajapaksa lobby signifying precisely nothing.

The danger however is that the vote in impending elections next year may be compelled by sheer disgust of the right royal mess being made in the corridors of power rather than a sensible contemplation of the worse horrors that an alternative may bring.

Some weeks ago, when engaging in an exchange of views on the state of politics in this resplendent isle with a more indifferent conversationalist, I was met with the cynical reflection that ‘Sri Lanka was in chaos when we were born, it remains in chaos while we live and assuredly it will be still in chaos when we die.’

That may indeed be a fitting epitaph for this nation and this land.

(Sunday Times)