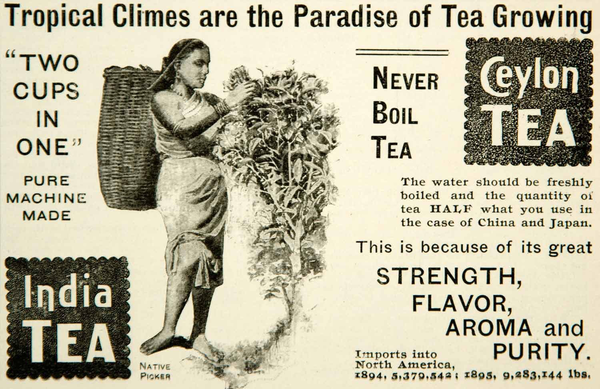

Image: A 1896 print advertisement for Ceylon Tea and India Tea. Photo credit: periodpaper.com

Vindhya Buthpitiya.

Ceylon tea might be distilled down to a popular image, a vision even, of vividly-attired Tamil women. Their nimble fingers sift through the parrot-green flush, effortlessly sweeping two-leaves-and-a-bud into wicker baskets to the rattle and shimmer of gold-and-glass bangles. Their faces are bright with toothy smiles, foreheads blessed with crimson kumkuma. Since the introduction of tea cultivation to the Subcontinent in the second half of the 19th century, visual renditions of women tea pluckers have circulated as widely as the leaves they tirelessly picked. Imprinted on ornate tins of Orange Pekoe to be steeped in bone china tea pots in polite London parlours, or in hand-coloured postcards exchanged between friends divided by oceans, these images have infused tea with a particular enchantment: a feminised mystique.

What is striking, however, is the persistence of such colonial imagery in marketing tropes across Southasia even today. The case in Sri Lanka is no different. Photographs of these women continue to feature in advertising not only for tea, but for luxury tourism and hospitality ventures which seek to market that imperial nostalgia for the strange terrains and peoples of faraway colonies. These invite tourists to relive the opulence of the Raj, as if centuries of conquest might be something one might casually revive. This reminds us of the enduring global inequalities between former rulers and subjects, and long histories of wealth drain. What is disconcerting, moreover, is how the picturesque commodification of colonial nostalgia – in both language and aesthetic – undermines the violence of Sri Lanka’s colonial encounter, and the sustained exploitation of estate communities on the island.

The line room experience

In June 2018, a post on a social-media account expressed disgust at an ‘experience’ offered by Sri Lanka’s famed Jetwing Hotels at its Warwick Gardens property in Nuwara Eliya District – one which, like many hospitality ventures based in Sri Lanka’s hill country, promotes “colonial luxury”. ‘Meena Amma’s Line Room Experience’ was presented as one designed to immerse guests “into the lives of Sri Lanka’s iconic tea pluckers” by way of two refurbished ‘line rooms’ – colonial-era accommodation for tea-estate workers that are known for their inhospitable living conditions. Jetwing’s line rooms, the website noted, “feature an attached bathroom with hot and cold water, as well as a living space adorned with a vintage rocking chair to relax in view of the misty mountains”. The “authentic local living” experience would permit guests to partake in the “simple pleasures” of the meals and “traditional activities characteristic of their lifestyle”. Priced at USD 97 per night (LKR 15,500), a stay in Meena Amma’s line room amounts to more than 20 days of a Sri Lankan tea plantation labourer’s daily wages at LKR 730 (USD 4.50) a day.

The post picked up traction, and its contents and concerns were widely shared on Facebook and Twitter. Many were outraged at how centuries of subjugation of the largely Indian-origin plantation community was being white-washed for the pleasure of tourists, ignoring the inhumane living and working conditions many plantation workers are subjected to even today. Such an initiative was particularly disappointing given Jetwing’s commitment to various community and environment projects.

Jetwing’s response to the outrage – the company’s chairman Hiran Cooray called it “a sensationalist view that completely ignores facts” – was patronising and defensive in its rationalisation. Its purported intention to “uplift” the plantation community (“the investments we have made in people,” the chairman notes) conveniently ignored the fact that the property is in fact located in their estate where the resident tea pickers are expected to satiate the curiosity of the “fascinated” tourists. Jetwing claims to show Meena Amma – a former tea plucker and “a loyal employee of Jetwing for 12 years” – as a positive exemplar of a worker with agency. It claims not to romanticise the lives of this community and acknowledges that their lives have “historically been very difficult”. But the difficulties are, in fact, not just historical and continue today. Few critics of Jetwing really expected the company to fix Sri Lankan’s plantation industry or ‘uplift’ every tea picker in the island. Their concern was directed at its obliviousness to history, and casual commodification using tropes that ignore the ongoing exploitation.

A brief history of displacement

Sri Lanka’s Indian-origin Tamil community, also known as Up-country Tamils, was brought to the island by British colonial administrators as indentured labour from rural India in the 19th century to carry out the gruelling tasks the locals were unwilling to take on. Large swathes of Sri Lanka’s infrastructure and plantation economy were built on their backs. Isolated from neighbouring villages in the hills in the Central and Sabaragamuva provinces, the group was marginalised by barriers of caste, ethnicity and language. In the plantations, they were subject to a strict regimen of strenuous labour in inhuman conditions. The barrack-style 10-by-12-feet line rooms housed entire families that were engaged in strenuous tasks aimed at carving out plantations from the hilly terrain. Following Sri Lanka’s Independence from Britain in 1948, the fate of the community, which had lived on the island’s tea estates for generations, became ensnared in the political changes.

Immediately after Independence, the majority of the Indian-origin Tamil community were disenfranchised by the Ceylon Citizenship Act (1948) and the Indian and Pakistani Residents (Citizenship) Act (1949). At the time, they constituted about 11 percent of the population, whose impact on elections was feared by many, in the prevailing atmosphere of the Sinhala nationalist sentiment. Under the 1948 act, citizenship was contingent on one’s father being born in Ceylon, which many Indian-origin Tamils were unable to prove due to the circulatory nature of early migration and lack of documentary proof. Only about 5000 Indian-origin Tamil individuals qualified for citizenship under these laws, making around 700,000 from the community stateless. The 1949 act relaxed earlier provisions, facilitating the citizenship of 100,000 more, based on criteria like uninterrupted residence, marriage and income.

But citizenship would remain difficult for some time. Persistent lobbying by political parties such as the Ceylon Workers’ Congress and a number of pacts with India (Nehru-Kotelawala Pact, 1954; Srima-Shastri Pact, 1964; and Sirimavo-Gandhi Pact, 1974) saw the repatriation of many Indian-origin Tamils who wanted Indian citizenship and resulted in securing Sri Lankan citizenship for others in the community. However, as late as 1982, some 86,000 Indian-origin Tamils were still without citizenship and were in the process of applying for it. It was only in 2003, following the passage of the Grant of Citizenship to Persons of Indian Origin Act, that Indian-origin Tamils living in Sri Lanka were finally guaranteed citizenship.

Specimens of empire

Comprising around four percent of the Sri Lankan population, Up-country Tamils are among the most marginalised ethnic groups in the country. Problems in government registrations, such as the arbitrary assignation of ethnic categories to children – due to the lack of land ownership, low literacy and ongoing contentions about the group’s ethnic categorisation – have resulted in difficulty in accessing basic state services and entitlements. Sometimes, some members of the same family are registered as Sri Lankan Tamils and others as Indian Tamils. As the main labour constituent of the Up-country tea estates, the community is also entangled in unequal and exploitative economic practices, which have continued despite some reforms, as the tea industry continues to rely on undignified, dehumanising labour practices. For the community, what was once a legal issue of recognising ethnic identity has today transformed into a struggle against socio-economic marginalisation.

But it isn’t just the estate workers’ labour that is exploited for private profit in the country and beyond; it is also the image of this community that is commoditised and fetishised. Images of tea pluckers – always female, even though this is not necessarily the case in practice – have become a trope that are often a part of marketing campaigns of tourism and hospitality industry of Sri Lanka. The potency of these exotic specimens of empire are such that wealthy travellers will pay to partake in a costly ‘pluck your own tea’ visits, which permits them, for about USD 25 (more than five days of a plantation worker wages), to dress up and pose for photographs as they mime the estate labour for an hour or two. Residents of plantations are compelled by plantations to present themselves and the more quaint, palatable aspects of their lives for the consumption of curious tourists. Jetwing’s ‘line-room experience’, which created the social-media uproar, was one of such schemes. These forms of tea tourism that coexist with the incredible hardship faced by estate workers are not unusual or new. In fact, such particularly crass recreation of the living conditions of Sri Lankan tea plantation workers, for the pleasure of those who can afford it, serves as an especially jarring manifestation of a deeply flawed global and local economy.

What is overlooked in these marketing campaigns are the long hours of back-breaking labour that do not amount to a fair living wage. They ignore the plantation owners’ demand for a daily minimum of 15 kilos of pluckings, which these women must carry on their backs as they navigate rocky paths to hilltops. In contrast to the luxurious replicas of workers’ quarters that places like Jetwing offer – with “contemporary amenities”, “attached toilets” or “hot water” – the workers return home to line rooms that have barely changed since the colonial period. They have poor access to running water and sanitation, and the homes sometimes house three generations of the same family even today.

These living conditions are especially burdensome and unsafe for women and children, exacerbating their vulnerability to sexual abuse and violence. A 2014 report published by the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) revealed that 66 percent of line houses, comprising over half of the accommodation occupied by estate workers, consist of one bed room, contributing not only to frequent illness, but also to domestic violence and sexual abuse exacerbated by high levels of alcoholism. The potency of the line room as an embodiment of a loathsome space and its ethnicised, discriminatory connotations continue to manifest in colloquial slurs against members of the Indian-origin Tamil community even today.

For the most part, the families do not have legal entitlement to these basic lodgings. Their ability to continue to live in the estate is contingent on at least one family member continuing to work there, even though they have been living there for generations. Those who are unable to meet this condition are relegated to the rather permanent ‘temporary shelters’, which are even less habitable than the line rooms. As they do not own their land and property but live in plantation accommodations, which are not necessarily visited by state-welfare officers, many are denied welfare services. Poor access to healthcare and emergency medical services has resulted in high rates of maternal and infant mortality, and child malnutrition. One in three babies born in the estates have a low birth weight and a third of women of reproductive age are malnourished.

Trade unions and activists since Independence have played a significant role in advocating for improvements in the wages, and living and working conditions of plantation labourers in Sri Lanka. Notable among these are the Institute for Social Development (ISD) in Kandy and the Red Flag Women’s Movement Sri Lanka, an independent women’s wing of the Ceylon Plantation Workers Union. The ISD in particular has long worked for the UTZ certification – an Amsterdam-based agricultural certification aimed at standardising sustainable farming and better labour practices – of tea estates, aside from founding The Tea Plantation Workers’ Museum and Archive in 2007. With this initiative, a few line rooms in Gampola, Kandy, were transformed into a museum that aims to preserve the community’s social and cultural history. There have been some improvements in the wage levels, too. In October 2016, after weeks of negotiations, tea-estate owners and trade unions agreed to a minimum daily wage of LKR 730 (USD 4.50), up from the previous rate of LKR 620 (USD 3.87) per day. The government has also pledged to provide some land and housing to plantation workers.

Still, enduring structural inequalities – poor access to education, underemployment, poverty and personal debt – have limited the opportunities for the members of this community. For some, urban informal labour and migrant work in West Asia has afforded considerable mobility. But for the vast majority of estate sector residents, line rooms continue to be a part of their lives. Many from the community who live in the hill country were also impacted by landslides in the past few years. Large groups from these areas have been compelled to live in tents with minimal access to water and sanitation for many months with little to no support from the estate management or the state to relocate and rebuild new houses.

Continued complicity

In a 1900 guide to the tea industry, Golden Tips: A Description of Ceylon and its Great Tea Industry, Henry W Cave writes, “Freedom they will always enjoy under British rule; but a just and almost paternal control, and a hand almost sparing in the direction of philanthropy are best suited to their needs.” He adds, “injudicious benevolence towards the Tamil coolie renders him useless for any purpose.” This paternalistic ethos still exists among the management of plantations even today, along with ethnic, casteist and classist bias against Indian-origin Tamil plantation workers. Reading Jetwing Hotels’ chairman’s response to the criticism of their ‘line rooms’ – his claim that the estate workers do their work “lovingly” and “are benefiting equally from the guests who stay at the line rooms” – the hospitality industry’s attitude to the workers doesn’t appear much different. Given this, the tourism industry’s packaging and presenting of the most disadvantaged and vulnerable among us as curiosities is callous and wilfully oblivious to their continued exploitation, making them complicit in this, too.

Seven decades after Independence, the past and present-day contribution of Sri Lanka’s Indian-origin Tamil in building and sustaining an industry, which has become synonymous with the country remains unacknowledged and inadequately recompensed. Estate residents continue to live in some of the harshest living and working conditions, and suffer from a range of socio-economic problems, from underemployment and malnutrition to alcoholism and sexual violence. Yet, in the words and pictures of companies like Jetwing, which seek to sell picturesque colonial nostalgia, they remain pinned to the emerald hillsides of the island’s mountains like jewel-toned Lepidoptera, exotic specimens of an old empire preserved by the new. They invite us to forget the tempest in each cup of tea.

~Vindhya Buthpitiya is a PhD candidate in Visual Anthropology researching the relationship between popular photography and articulations of Tamil identity and citizenship in post-war Sri Lanka. She has held numerous consultancy positions in social and policy research within the public, private and non-governmental sectors in Sri Lanka, with a focus on postwar reconciliation and development, and community-environment relationships.

-Himal Southasian