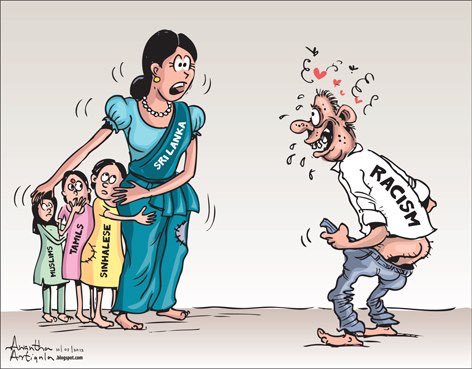

Racism is a political theme that has attracted a great deal of public attention in Sri Lanka last week. The attacks on the life and property of Muslim citizens in several locations in the Kandy District by Sinhalese mobs has provided the context for renewed public attention on the negative and destructive consequences of racist politics.

There seems to be two opposing responses to these particular events of racism.

The first, which is being openly expressed, condemns racism and views it as a hindrance to peaceful community relations as well as the country’s progress.

The second, which is being expressed in private conversations, is mildly critical of the acts of violence against Muslims, yet, claims for it a political rationale and justification.

From that perspective, when the legitimate ‘place’ of the majority community in a multi-ethnic society is at stake, and when the government shows only a passive reaction to it, radical groups justifiably turn to violence to protect the majority’s interests.

It is the second perspective that tells us that racism has actually been an expression of a widely shared political consciousness in Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese Buddhist society. Racism is a shorthand concept to describe that particular mode of political consciousness which we find among majority ethnic communities in many multi-ethnic societies in the world. It is rooted in a peculiarly minoritarian complex among ethnic majorities.

Two meanings

Racism has two inter-related meanings, the first is an idea and the second is a political practice. As an idea, it is an expression of a belief, shared by members of a particular ethnic community –majority or minority –, of its superiority over other communities, on the basis of race, culture, language, skin colour, and history. As a mode of political and social practice, racism is associated with acts of prejudice, discrimination, bigotry, and intolerance. It produces state policies that institutionalize group inequality as well as the denial of human dignity to some citizens as communities.

The extreme instance of racist political practice is the use of violence and terror against communities that are viewed as inferior and unequal. It comes with a process of ‘othering’ the other. Carl Schmitt’s famous formulation of politics as expression of friend – enemy distinction, actually, came in the context of militant Nazi racism in Germany.

Racism is also a particular kind of majoritarian ethnic nationalism, an extreme manifestation of nationalist consciousness, with a set of properties specific to it. Sri Lanka’s experience helps us to delineate the line of demarcation between nationalism and racism.

Shades of nationalism

In Sri Lanka, nationalism as an ideology and a specific form of political practice is actually spread across a broad spectrum. There are indeed nationalisms within nationalisms. Let us take Sinhalese and Tamil nationalism as examples. Each has within its fold a variety of shades, with moderate to extreme political imaginations, programs, and commitments. The moderate ones are committed to a program of nation-state nationalism, de-emphasizing the ethnic appeal of nationalist politics. The UNP after 1987, the SLFP occasionally (under Presidents Chandrika Kumaratunga and Maithripala Sirisena) have shared this mainstream, and nationalist politics in Sri Lanka. Nation-state nationalism of the UNP and SLFP does not promote friend-enemy distinction within the multi-ethnic nation.

Then, the SLFP before 1994 as well as under the leadership of Mahinda Rajapaksa, and the UNP before 1987, represented the conventional mode of Sinhalese ethnic majoritarian nationalism. Thus, the nationalist ideologies of both, the old UNP and SLFP had in the past accommodated mild versions of Sinhalese racism, prevalent among sections of the Sinhalese-Buddhist vernacular intelligentsia.

The old nationalism of the UNP and the SLFP had a basic commitment to establishing the dominance of the Sinhalese ethnic group over the minority ethnic groups by means of state capture. It did not advocate a friend-enemy distinction among ethnic communities, but was firmly committed to establishing an ethnic hierarchy in the Sri Lankan polity.

In this vision of ethnic hierarchy, the majority and minority communities were recognized as unequal entities in terms of political power and citizenship rights. The UNP abandoned this majoritarian ethno-nationalist project after 1987. The SLFP followed suit in 1994, but revived the old ideology in 2005. At present, the SLFP seems to be torn between an accommodationist nation-statist nationalism and rigid ethnic majoritarian nationalism.

The JVP and JHU represent two different, yet extremely interesting, forms of nationalist politics. The JVP’s nationalism is a socialist type of nation-state nationalism which believes in inter-group equality primarily in terms of social, economic and cultural rights of the minorities. In terms of political rights of the ethnic minorities, the JVP believes paradoxically in a liberal program in which individual, civil, political and social rights, and cultruralist group rights are accommodated. However, the JVP continues to be opposed to political group rights of the minorities, as old liberals and socialists do, such as devolution, self-rule and regional autonomy.

Thus, the JVP represents a moderate version of nation-state nationalism. And, because of its strange combination of socialist and liberal positions, the JVP’s nationalism does not have room for racism.

The JHU, interestingly, originated with a great deal of potential for racism, but, surprisingly, has moved towards embracing a vague form of nation-state nationalism. In the latter, a minimalist political accommodation between majority and minority ethnic communities is conditionally tolerated. Bhikku Athuraliye Ratana’s shift to ecological populism and Minister Champika Ranawaka’s preoccupation with his future political ambitions of becoming a national leader seem to have fostered a peculiar process of de-radicalization of the JHU. Thus, the JHU, to the chargin of many of its former followers and urban middle-class well wishers, seems to have abdicated its capacity to nourish racist politics in Sinhalese society.

Now, let us turn to the question of racism in Sinhalese society. The spread of moderate, semi-moderate and nation-statist nationalisms in Sinhalese society, despite, and also because of, the ethnic war, seems to have provided the context for the recent emergence of racist activism in the Sinhalese society. De-radicalization of nationalisms of mainstream political parties has provided the impetus for Bodu Bala Sena (BBS) and Ravana Balakaya (RB) to emerge. De-radicalization of the JHU is also a proximate reason, because it created a ‘militancy vacuum’ in Sinhalese nationalist politics.

Antecedents

There are antecedents to BBS and RB that go back to the mid 1950s. Its first manifestation was Jathika Vimukthi Peramuna, led by K. M. P. Rajaratne and Kusuma Rajaratne – a husband-wife duo – who preached an extreme form of racial hatred against the up-country Plantation Tamils. With their intolerant brand of Sinhalese racism, they also won parliamentary seats at the 1956 election, and later from multi ethnic electorates.

The Rajaratnes preached an extreme ideology of Sinhalese nationalism whose key point was that the Sinhalese villagers in the central hill country had an immediate enemy – the ‘Indian origin’ Tamils. The Rajaratne couple constructed the first post-colonial political doctrine of Sinhalese racism –collective group insecurity being its dominant theme — during the early and mid 1950s. Its second phase was led by Cyril Mathew, a UNP politician from a trading family in Colombo, and Ven. Madihe Pannasiha, a respected Buddhist prelate belonging to the Amarapura fraternity.

Both, Mathew and Ven. Madihe gave a distinctly militant character to Sinhalese nationalism, making it exclusively anti-Tamil and anti-Christian. They did so by constructing an ideology for the Sinhalese with the central argument that the Sinhalese-Buddhists were an endangered majority, with the risk of becoming a disempowered minority, in their own land of origin and destiny.

The two Rajaratnes, Mathew and Ven. Madihe Pannasiha’s intellectual contribution to an extreme strand of Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalism in post-colonial Sri Lanka deserves at least belated acknowledgement. They continued an ideological movement initiated by L. H. Mettananda and N. Q. Dias during the 1950s.

Then comes the Jathika Chinthanaya group of Nalin de Silva and Gunadasa Amarasekara, two Colombo based intellectuals with rural socio-cultural origins. Both of them are ex-Leftists. They, in a way re-constructed Sinhalese nationalist ideology at a time when Tamil minority nationalists were challenging the state, which the Sinhalese nationalists had thought was under their possession and control. De Silva particularly, made a noteworthy contribution to the racist imagination of Sinhalese nationalism. He made a sustained argument that the Sinhalese Buddhists were intellectually, philosophically, and culturally far superior to Tamils, Muslims, and Christians all of whom, as he claimed, had inferior histories, cultures and legacies.

If a belief in unparalleled ethnic superiority of an ethnic community is the hallmark of racism, Nalin de Silva’s contribution to that strand of Sinhalese nationalist thought is phenomenal.

The BBS

The BBS and RB have inherited these multiple legacies of racism of Sinhalese nationalist ideology and carried forward a political practice of violence that was initiated at a low key level by the National Movement Against Terrorism (N-MAT). This was a small outfit affiliated to the Hela Urumaya. It became active during the late 1990s. With its de-radicalization, the JHU seems to have disbanded the N-MAT. Some of its ex-cadres seem to have formed their own new entity, the BBS. This genealogy of the BBS puts in context the statement which Minister Champika Ranawaka recently made to deny any link with the BBS. Meanwhile, the RB has links with Wimal Weerasansa’s National Freedom Front.

The Mahason Balakaya, from all the information available, is a creature of the Facebook and social media, with only a handful of digital activists. In the age of social media and cyber activism, even a single person with an extremist agenda that spawns fear, hatred, and heroism does not need a well-funded or well-knit organization to create a generalized sense of hysteria and terror. It is an example of post-modern terror ‘movements’ with no centre, no large membership, no organization, and no location.

Now, what is it that makes BBS racism special? It represents a stage of maturity of racist politics in Sinhalese society with its open commitment to generating hatred among ethnic communities and provoking violence to target a specific minority community at present. The BBS interestingly is not an underground organization. It functions openly and offers racism as an alternative, and respectable, political doctrine with a vision for emerging itself as a legitimate political force. Its ideology seems to have been informed by a crude version of just war theory. And its political practice employs open violence.

What is interesting to watch now is how the present political uncertainty and governance crisis would enable the BBS to penetrate further the political consciousness of Sinhalese society. The real danger of entities like the BBS is not their potential to become a major electoral force, but their capacity to define the terms of the country’s political discourse while remaining a small activist group of dedicated cadres.

First published in Sunday Observer.