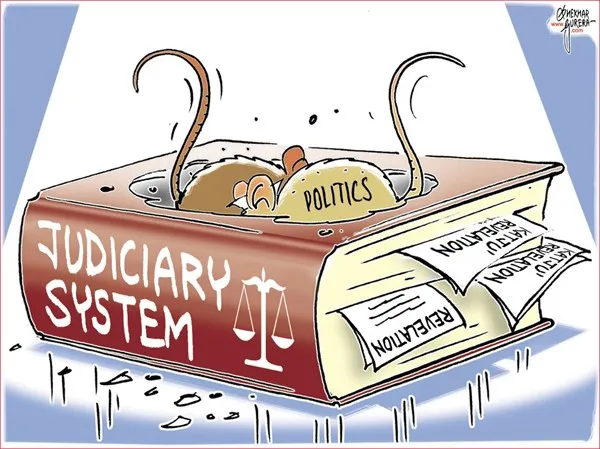

Cartoon from internet and does not related to the article.

Removal of the PM

The Twenty-Second Amendment to the Constitution Bill (22A) was showcased by the Wickremesinghe-Rajapaksa Government as a restoration of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution (19A) of 2015. Most 19A provisions were removed by the Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution. Many, including the writer, have pointed out that not all the provisions of 19A are sought to be introduced by 22A. The 22A Bill was challenged in the Supreme Court, mostly by Sinhala nationalist groups, who consider the Presidential form of government to be one assurance of majoritarian dominance.

The demand for abolishing ‘Executive Presidency’

The abolition of the ‘Executive Presidency’ was one of the significant demands of the Aragalaya, while going back to 19A was called for as an immediate measure. Over the last year or so, support for the abolition of the Executive Presidency has seen a marked increase. A survey conducted by the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) in April 2022 revealed that 74% of the respondents wished for the complete abolition of the Executive Presidency, compared to 50.3% in October-November 2021. It is of interest that the figure among the Sinhalese, who wish for abolition (74.2%) was higher than the national percentage, clearly indicating that Sinhala nationalism is on the retreat.

The Supreme Court (Jayasuriya CJ, Aluwihare J and Obeysekere J) has determined that several key provisions of 22A require the approval of the people, at a referendum, in addition to a two-thirds majority, in Parliament. They are as follows: the President should not have the power to dismiss the Prime Minister; Ministers shall be appointed by the President on the advice of the Prime Minister; and that if the President does not make appointments to the independent Commissions, as recommended by the Constitutional Council, within 14 days, the appointments would be deemed to have been made.

Rejection of the 19 A

These three provisions were part of the Constitution, under 19A. The Supreme Court, in 2015, did not consider that they would require approval, by the people, at a referendum. There is thus a clear shift in the thinking of the current Supreme Court. The government has said that a referendum will be avoided by amending the Bill at the committee stage in Parliament. Thus, the President would only be required to consult the Prime Minister in appointing Ministers. The President can dismiss a Prime Minister even when the latter has a clear majority in Parliament. Premier Dinesh Gunawardena, beware!

Appointment and removal of PM

To the writer, the decision of the Supreme Court in the matter of appointing Ministers did not come as a surprise, given the reasoning of the Court (Jayasuriya CJ, Janak De Silva J and Obeysekere J) in its determination of the Samagi Jana Balavegaya’s Twenty-first Amendment to the Constitution Bill (21A), holding that the abolition of the Executive Presidency required people’s approval, at a referendum. The writer disagrees with that determination, which will be the subject of a forthcoming paper. But the determination in the 22A case that the President’s power to dismiss a Prime Minister, who commands the confidence of Parliament, is an essential part of executive power, did come as a surprise.

The Nineteenth Amendment took away the power of the President under previous Article 47(a) to remove the Prime Minister. The removal of the Prime Minister thus became a power of Parliament. New Article 48(2) provided that if Parliament rejects the statement of government policy, or the Appropriation Bill, or passes a vote of no-confidence in the government, the Cabinet of Ministers shall stand dissolved. The President could then appoint a new Prime Minister.

“It is respectfully submitted that the learned Judges were in error in both the 20A and 22A cases. Both 19A and 20A had a similar provision, relating to the appointment of the Prime Minister”

The 20A Bill sought to empower the President to remove the Prime Minister. The proposed provision was challenged. A five-member Bench of the Supreme Court, however, held that in view of the fact that the President, who holds the People’s executive power in trust for the People, is the Head of the Cabinet of Ministers and the appointing authority of the Prime Minister, empowering the President to remove the Prime Minister and appoint a new Prime Minister who, in his opinion, commands the confidence of Parliament, does not infringe the sovereignty of the People. The Court did not explicitly state that such a power of removal is an essential part of executive power but seems to have gone on the basis that the appointing authority also has the power of removal.

In the 22A case, the Attorney-General submitted that the removal of the Prime Minister should arise only where the Prime Minister ceases or fails to command the confidence of Parliament and that in such an instance, it is more appropriate for Parliament to move a motion of no-confidence against the Prime Minister. He submitted further that the President, acting on his own accord in removing the Prime Minister, where he is of the opinion that the Prime Minister no longer commands the confidence of Parliament, would amount to an arbitrary exercise of power. The Court’s response was that currently, that is under 20A, the President has the power to remove the Prime Minister. The circumstances in which the Prime Minister may be removed will not be limited to a situation where the Prime Minister no longer commands the confidence of Parliament. The Court took the view that taking away that right affects the balance of power that currently exists and amounts to a relinquishment and erosion of the executive powers of the President, impinging upon the sovereignty of the People.

It is respectfully submitted that the learned Judges were in error in both the 20A and 22A cases. Both 19A and 20A had a similar provision, relating to the appointment of the Prime Minister: ‘The President shall appoint as Prime Minister the Member of Parliament, who, in the President’s opinion, is most likely to command the confidence of Parliament.’ The word ‘most’, which makes all the difference, escaped the attention of the learned Judges in the 20A case, who assumed the wording to be ‘who in the President’s opinion, is likely to command the confidence of Parliament’. It is clear that the President has no discretion in the matter of appointing a Prime Minister. He must necessarily appoint ‘the Member of Parliament’ who, in his opinion, is most likely to command the confidence of Parliament. The Sinhala version of Article 42(4) is even more clear, using the phrase ‘vishvaasaya uparima vashayen athi’ (‘utmost confidence’).

Thus, there can be only one Member of Parliament, who fits the constitutional requirement. That Member has a right to be appointed as the Prime Minister. To use equal protection phraseology, the office of the Prime Minister is a single-person class, a class which consists of one person. It follows that a ‘new Prime Minister’ cannot be the Member of Parliament who commands the ‘utmost confidence’ of Parliament, that Member of Parliament having been removed. It is submitted that to empower an authority to remove the one person who is entitled to be in a single-person class is arbitrary.

Public Trust Doctrine

Our courts have, on countless occasions, reiterated the application of the public trust doctrine to the exercise of power. In Re Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution 2002, a seven-member Bench of the Supreme Court reiterated that the doctrine applies to powers of check attributed to one organ of government in relation to another: ‘The power that constitutes a check, attributed to one organ of government in relation to another, has to be seen at all times and exercised, where necessary, in trust for the People. This is not a novel concept. The basic premise of Public Law is that power is held in trust.’

It thus follows that the power to dismiss a Prime Minister at will when Parliament is functioning properly and the Prime Minister commands the confidence of Parliament is an obvious violation of the doctrine.

22A sought to remedy this situation, as 19A did, by taking away the power of the President to remove the Prime Minister.

(The Island)