Expert Speak Raisina Debates

(ORF) In Sri Lanka, the new government of President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has decided not to sell the state-owned enterprise (SOE)—Sri Lankan Airlines. The decision mirrors the government of former President Ranil Wickremesinghe, who also scrapped plans to privatise Sri Lankan Airlines in July. State-owned enterprises have impacted Sri Lanka’s economy for decades. Sri Lanka defaulted on its sovereign debt in April 2022 amid power blackouts and long fuel queues, with its Central Bank reserves dropping below US$ 50 million. It is going through its worst economic crisis since its independence and is currently on its 17th International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme. It is also in the process of finalising debt restructuring negotiations with its external creditors.

Sri Lanka defaulted on its sovereign debt in April 2022 amid power blackouts and long fuel queues, with its Central Bank reserves dropping below US$ 50 million.

Short-term reasons for Sri Lanka’s economic crisis can largely be attributed to the government that took power in 2019. It made several disastrous economic policy missteps, including giving unaffordable tax cuts that resulted in Sri Lanka losing access to international capital markets, adopting the modern monetary theory, pegging the currency, and enacting an overnight ban on chemical fertilisers, all while not engaging with the IMF early in 2020. But Sri Lanka’s economic crisis also has structural causes: decades of large fiscal deficit covered by debt and monetary financing, a culture of political parties promising subsidies and government jobs which have created loss-making SOEs, a low tax-to-GDP ratio, especially from the mid-1990s, protectionist policies, the lack of Free Trade Agreements (FTA), a low position in ease of doing business rankings, inconsistent policies, and outdated land and labour laws.

Opportunity costs of Sri Lanka’s state-owned enterprises

India is forecasted to spend more than 1.5 percent of its GDP on roads and railways alone. In stark comparison, Sri Lanka’s national airlines alone made losses of over 1 percent of Sri Lanka’s GDP. The losses of one of Sri Lanka’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs), Ceylon Petroleum Corporation in the first four months of 2022 was greater than Sri Lanka’s education and health budgets for 2023 combined. These two facts bring attention to not just the financial costs of SOE losses, but also the opportunity cost of depriving investment in infrastructure, education, and health which has a long-term socio-economic impact.

The losses of one of Sri Lanka’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs), Ceylon Petroleum Corporation in the first four months of 2022 was greater than Sri Lanka’s education and health budgets for 2023 combined.

SOE losses can be attributed to mismanagement, overstaffing, the lack of financial disclosure and the lack of budgetary constraints. It is also interesting to note that the labour costs are 70 percent higher in SOEs when compared to the private sector, which adds pressure to fiscal policy. In 2021, 86 percent of government revenue in Sri Lanka went to paying for the salaries and pensions of state sector employees. This has direct implications on fiscal policy-making, with the government severely constrained when it comes to spending on infrastructure, education, health and R&D, resulting in slower economic growth.

The cost of operating inefficient SOEs is not only financial but has wider implications for the economy as a whole. As Sri Lanka has one of the lowest tax-to-GDP ratios in the world, to sustain SOEs, successive governments have resorted to monetary financing, which has resulted in the country consistently having a higher inflation rate when compared to the rest of South Asia. This has led to high interest rates, resulting in higher borrowing costs for Sri Lankan businesses, placing them at a disadvantage globally. The Treasury has also used debt financing and borrowing, especially from the two state-owned banks, leading to higher borrowing costs for the private sector. People are employed largely through SOEs, accounting for around 1.4 million people. This is nearly one in six of the total workforce, resulting in a shortage of labour for the private sector.

Some of the negative effects are higher borrowing costs to sustain SOE losses, crowding out effects on capital and labour as credit, and a lack of labour in the private sector due to the draws of SOEs.

The fact that many state employees are given pensions also incentivises people to seek government jobs, which also partly explains why Sri Lanka has a low percentage of the population becoming entrepreneurs. Some of the negative effects are higher borrowing costs to sustain SOE losses, crowding out effects on capital and labour as credit, and a lack of labour in the private sector due to the draws of SOEs. Inefficient SOEs in critical sectors like energy, telecom, and ports have slowed down many other industries which depend on them. These reasons have contributed to Sri Lanka’s slow economic growth over decades.

Recommendations

With state-owned enterprises in Sri Lanka causing economic damage to the wider economy, possible solutions to address these issues are explored below:

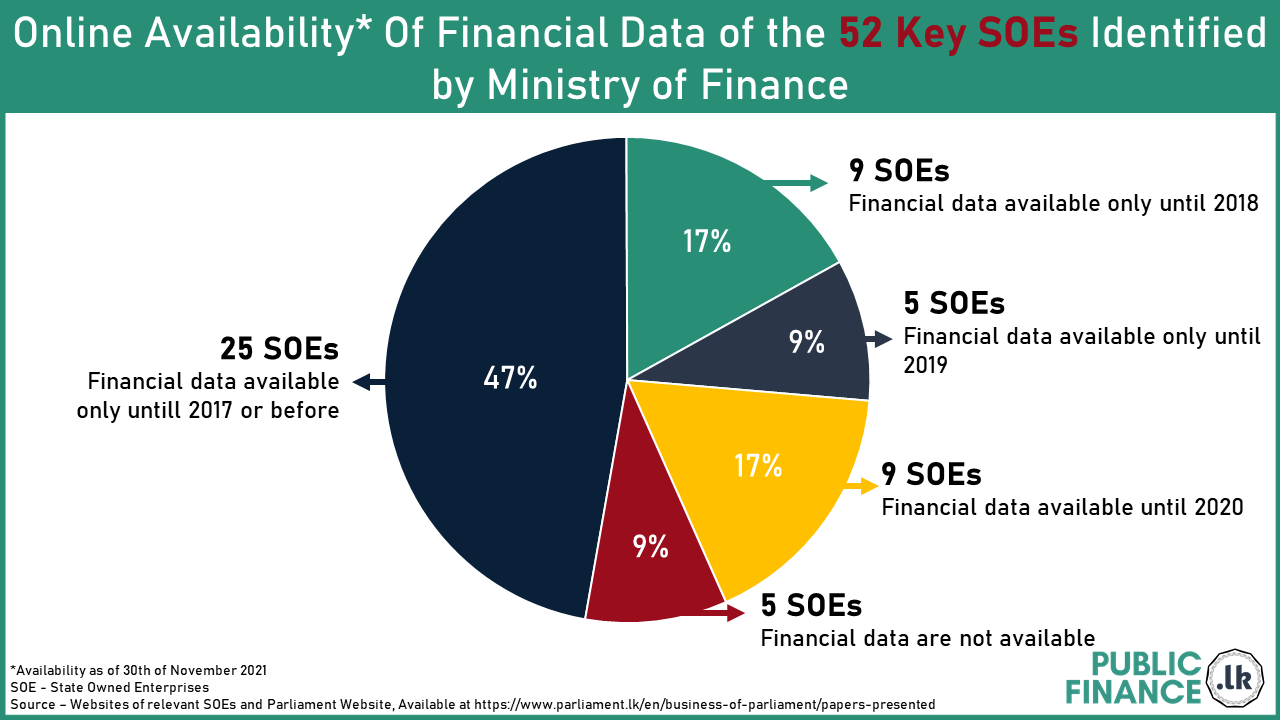

Increase transparency and accountability: The first step would be establishing standard reporting systems. This can allow the government to audit and assess the performance of SOEs and note how they comply with corporate governance standards. Clear Key Performance Indicators (KPI) and objectives should be set, which include financial targets, sustainability targets, and capital structure objectives. An independent board of directors should be appointed based on merit. This will also mean that remunerations should be set at higher levels so they can attract talented and qualified professionals. A framework should be created that sets clear responsibilities in the organisation and defines levels of authority. There should be a requirement to publish annual reports which are accessible to the public. Transparency and accountability in SOEs make them more attractive to investors if the government later decides to privatise. The graph below shows that for the 52 key SOEs in 2021, over half of them do not have any available financial data or have it only until 2017.

Source: Publicfinance.lk

Restructure SOEs: Realign SOEsto their original goals, which may have been fostering economic growth or providing essential services efficiently and cost effectively. This will also streamline operations with targeted performance metrics. Since SOEs are overstaffed, restructuring them can reduce redundant positions, boosting process efficiency. A leaner SOE which uses digitisation and innovation can have spillover effects on the rest of the economy. For instance, the privatisation of Sri Lanka Telecom prompted the liberalisation of the telecom industry in the 1990s, leading to wider positive implications for the Sri Lankan economy, including rapid growth in the telecom sector at 45 percent annual growth in 1998-99. Selling off non-core assets can help provide essential capital for future investments.

The privatisation of Sri Lanka Telecom prompted the liberalisation of the telecom industry in the 1990s, leading to wider positive implications for the Sri Lankan economy, including rapid growth in the telecom sector at 45 percent annual growth in 1998-99.

Establish a super holding company: A key benefit of this strategy is that the government can focus on policy-making and regulation. The Sri Lankan Finance Ministry and the respective subject ministry will not be involved in the management and operational decision-making. Singapore’s Temasek Holdings is a good example of a successful super holding company. SOEs under Temasek have higher valuations and better corporate governance than private companies in Singapore. Sri Lanka could mimic the success of Temasek: by ensuring better board governance which focuses on the business charter and recruitment of the best talent.

Privatisation: This would be the most financially attractive but politically costly action for the Sri Lankan government. Selling off SOEs can bring in much-needed capital, especially foreign exchange if sold to foreign investors. This can reduce the strain on the treasury and help gear up the government to focus on policymaking and regulation. Privatisation also will result in greater efficiency, as proven by the Sri Lankan airlines, when it was managed by Emirates before 2008. Ideally, SOEs like hotels and retail chains can be fully privatised. That said, it is also important to liberalise industries and allow for competition before privatisation. The government can also gain through tax revenue paid by privatised entities, which will also lead to Sri Lanka attracting more foreign investments because a private company is more attractive to international investors than an SOE. A public-private partnership can also be looked at, with the private sector owning a fair share and being in charge of management.

A combination of options will have to be examined following a detailed assessment of the specific enterprise and the overall landscape of its operating sector.

Conclusion

As Sri Lanka’s SOEs have diverse structural problems, a one-size-fits-all solution may not be feasible. A combination of options will have to be examined following a detailed assessment of the specific enterprise and the overall landscape of its operating sector. Some of the solutions, such as increasing accountability, restructuring SOEs and privatisation were not done on a wide scale due to political costs and pressure from trade unions. A super holding company like Temasek in Singapore also would have been unpopular among ministers since it would take the control of SOEs away from line ministries. But this time, there is a general public consensus that action has to be taken on SOEs. Other options the government has, such as increasing taxes or cutting down on state expenditure will be far more unpopular among the general population.

A reconfiguration of SOEs will be inevitable for Sri Lanka to meet the IMF’s fiscal consolidation targets. Increasing accountability, restructuring, privatising and using a super holding company are all viable options that can help Sri Lanka’s expenditure-based fiscal consolidation, reducing pressure on domestic banks and resulting in more access to finance and a lowering of labour costs for the private sector.

Talal Rafi is an Economist and an Expert Member of the World Economic Forum.

Courtesy of the ORF