(Geneva) – The Sri Lankan government has failed to fulfill its pledge to abolish the abusive Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. For decades, the PTA has been used to arbitrarily detain suspects for months and often years without charge or trial, facilitating torture, and other abuse.

“The Sri Lankan government has been all talk and no action on repealing the reviled PTA,” said Brad Adams, Asia director. “Replacing this draconian counterterrorism law with one that meets international standards should be an urgent priority if the government is serious about protecting human rights.”

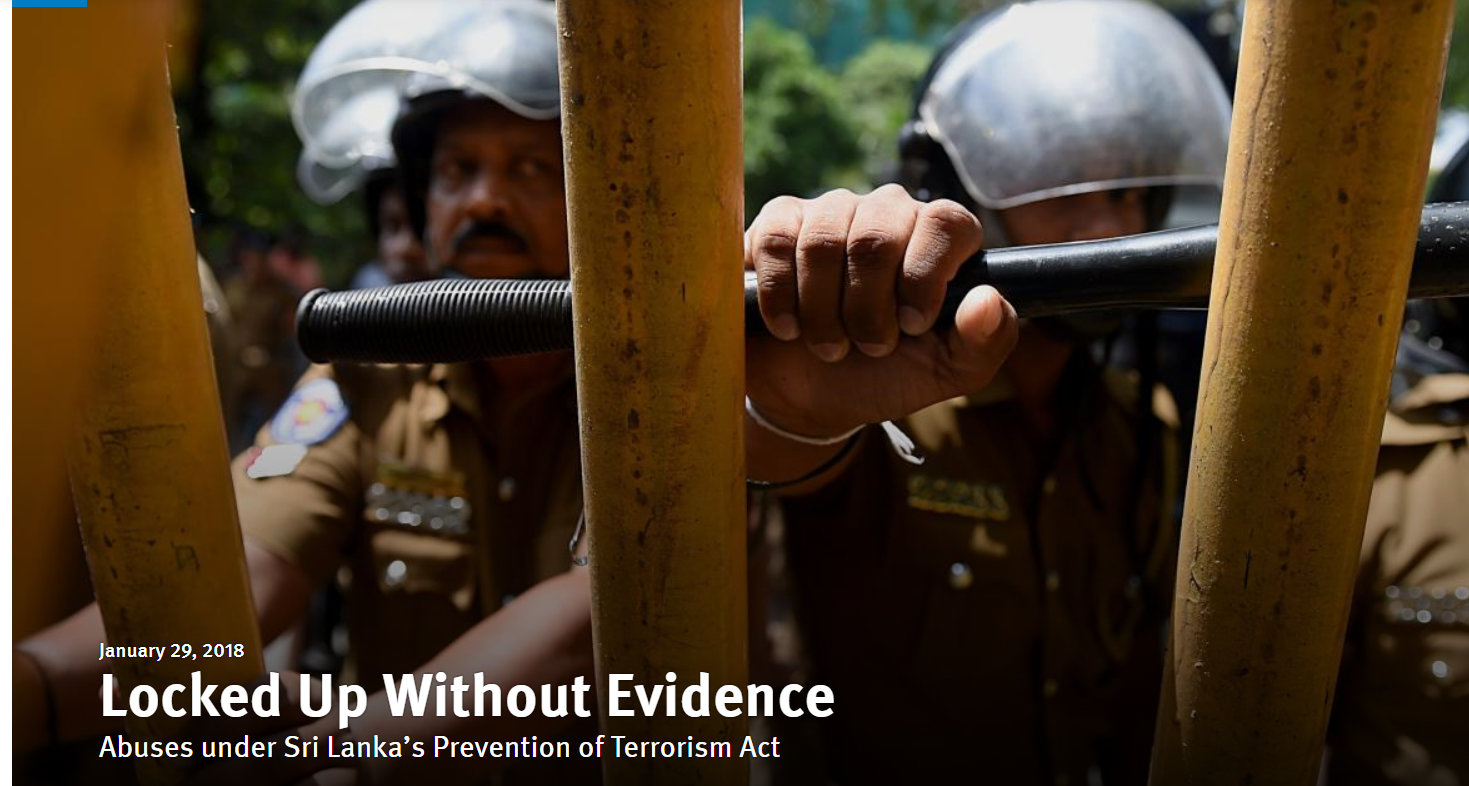

The 46-page report, “Locked Up Without Evidence: Abuses under Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act,” documents previous and ongoing abuses committed under the PTA, including torture and sexual abuse, forced confessions, and systematic denials of due process. Drawing on interviews with former detainees, family members, and lawyers working on PTA cases, Human Rights Watch found that the PTA is a significant contributing factor toward the persistence of torture in Sri Lanka. The 17 accounts documented in the report represent only a tiny fraction of PTA cases overall, but they underscore the law’s draconian nature and abusive implementation.

[alert type=”success or warning or info or danger”]

Locked Up Without Evidence

Abuses under Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act

[/alert]

The PTA was enacted in 1979 to counter separatist insurgencies, notably the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and the law was widely used to detain hundreds of people during the country’s 26-year-long civil war. Yet while other emergency regulations have lapsed since the conflict ended in May 2009, the PTA remains in effect.

The Sri Lankan government arrested at least 11 people under the PTA in 2016 for alleged terrorist activities.

The PTA allows arrests without warrant for unspecified “unlawful activities,” and permits detention for up to 18 months without producing the suspect before a court. Human Rights Watch has received several reports of people detained for a decade or more without access to legal recourse, who were subsequently acquitted or released without charge, yet received no compensation, reparations, or apologies from the government. Government figures released in July 2017 indicate that 70 prisoners have been held in pretrial detention under the PTA for more than five years, and 12 for over 10 years.

Many of those detained under the PTA described being tortured to extract confessions. Of the 17 individuals whose cases are detailed in the report, 11 reported beatings and torture. Human Rights Watch has previously documented cases where security forces raped detainees, burned their genitals or breasts with cigarettes, and caused other injuries through beatings and electric shock.

A senior judge responsible for handling PTA cases said he was forced to exclude confession evidence in more than 90 percent of cases he had heard in 2017 because it was obtained through the use or threat of force. Former detainees frequently suffer from psychological and physical trauma as a result of their incarceration and ill-treatment in custody.

The PTA provides immunity for government officials responsible for abuses if deemed to have been acting in good faith or fulfilling an order under the act, which gives broad cover to security force personnel to engage in torture and other abuses.

After a two-week country visit in December, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention called for an immediate repeal of the PTA, referring to it as a “key enabler” of abuse. The European Union also reiterated its call for the PTA to be repealed at an EU-Sri Lanka Joint Commission meeting in January 2018.

The Sri Lankan government agreed to a resolution at the UN Human Rights Council in October 2015 outlining a series of commitments on accountability and justice. Yet more than two years on, it has largely failed to implement key pledges on security sector reform, including repealing the PTA. The UN high commissioner for human rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, highlighted Sri Lanka’s lack of progress in his opening remarks at the 36th session of the Human Rights Council in September 2017, calling on the government to realize that its obligations are not a mere “box-ticking exercise.” At Sri Lanka’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in Geneva in November, several UN member countries pressed the government to implement safeguards against torture and repeal the PTA.

While the government of President Maithripala Sirisena has taken some steps to charge or release PTA detainees, it has not put forward a plan to provide redress for those unjustly detained, or addressed the issue of detainees charged and prosecuted solely on the basis of coerced confessions obtained during detention.

Although the government has floated several drafts of a new counterterrorism law, none have complied with international human rights standards. In May 2017, the cabinet approved with little public consultation a draft Counter Terrorism Act (CTA) to replace the PTA. Although the bill improves upon the PTA in some ways, it still allows prolonged arbitrary detention, enabling rights abuses such as torture. It also includes broad and vague definitions of terrorist acts, which could be used to criminalize peaceful political activity or protest. Ultimately, the proposed law falls far short of the government’s commitments to the Human Rights Council, and suggests it does not intend to fully relinquish the broad and too easily abused powers available to it under the PTA.

Rather than enacting a law that will perpetuate the wrongs committed for decades under the PTA, the government should consult with Sri Lankan victim groups, human rights organizations, and international experts to draft a law that protects both national security and human rights. This should be undertaken as one component of broader security sector reforms, including accountability for abuses carried out under the PTA.

“The 2015 Human Rights Council resolution did not mean an end to international scrutiny of Sri Lanka,” Adams said. “Rather, it offered tangible benchmarks that UN member countries should draw on to highlight Sri Lanka’s lack of progress and press for needed reform.”

Cases from the Report

Vijaykumar Keetheswaran

Vijaykumar Keetheswaran, a student in Colombo, was visiting his family in Kilinochchi when he was arrested under the PTA in June 2014. He alleges that he was tortured in custody by Terrorist Investigation Division (TID) officials during questioning about his contact with a Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) fighter:

This unit beat me on my back with sticks and poles. They stripped me naked, and beat the soles of my feet with pipes. At one point, they rubbed a chili paste on my genitals. I fainted at that point.

In July 2014, Keetheswaran was transferred to Boosa, a maximum-security prison in southern Sri Lanka where many PTA detainees have been held. He was produced before a magistrate in March 2015, after nine months in custody. “Before going to the magistrate, the TID wanted me to sign a confession, and they burned me with cigarettes,” he said.

Keetheswaran was released on bail in November 2015, but arrested again under the PTA in April 2016 and detained for five months, when the TID was searching for his brother:

When they couldn’t find [my brother], they arrested me instead. I was taken to Boosa and tortured all over again. They asked me to admit that my brother had been in the LTTE. I was hanged and beaten so badly that I admitted to it even though I don’t know if it’s true or not.… I was 13-years-old when the war ended. I didn’t even know what the LTTE was. But I’m still being harassed.

Sahan Kirthi

Sahan Kirthi, then 21, was arrested under the PTA in February 2007. He was at first detained for six months, during which he said he endured weeks of torture by TID officials. He told Human Rights Watch:

There was a pattern to the torture. They would take a plastic shopping bag, pour some petrol into it, and then cover my head with the plastic bag. It forced me to breathe the petrol simply to try and get some air. I was beaten on the soles of my feet. The pain was unbearable. I could feel my heart beat and I would get terrible headaches. There was also water torture, where they would put a handkerchief over my face, and put my face under a running tap with high pressure. If you breathe, the water goes into your nose and you feel like you are drowning. At the same time, you can’t really breathe because the water pressure is so high.

TID officials tried to force Kirthi to confess, even threatening to rape his sister. When he was produced before a magistrate after six months, he attempted to report the torture to judicial and medical representatives:

When I was produced before the magistrate, I started telling my story. She called us into her chambers instead and scolded me for saying that the TID had tortured me. I showed her my wounds and scars and she said, “You must have hit yourself.” … I was produced before a JMO [Judicial Medical Officer] after agreeing to sign a confession.… They would not let me read what was written down, so I have no idea what I supposedly confessed to. The JMO didn’t listen to me – there is a network between the JMO, magistrate, and TID, I am certain of that. They protect each other.

Kirthi was transferred to Welikada Prison in Colombo in June 2007 but was not formally charged until 2012. He was eventually acquitted in October 2014 after seven years in prison. Kirthi still has injuries, including loss of hearing, from the torture he endured in custody.

Durga

Malathi’s son, Kanna, was arrested by police in Matale in 2008 on suspicion of involvement with the LTTE. He was released after a week in custody and went into hiding. Malathi (a pseudonym) has not heard from him since. Shortly after Kanna’s release, TID officials returned to his house to search for him. When they learned he was missing, they arrested his wife, Durga (a pseudonym), instead. She was held in custody for six months before being produced before a magistrate, and then detained in prison for a further six years before any charges were filed. In 2015, she was acquitted of all charges and released, after seven years in detention.

Durga remains psychologically and physically impaired because of her long incarceration. Her three young children, who were 18 months, 3 years, and 7 years old at the time of her arrest, were raised by her mother-in-law. Malathi said things have been difficult for Durga:

Durga is out of prison now, but is broken. She is not strong enough to take a job on the tea estates, so does menial chores in the bungalows. We have not received any apologies or compensation for our suffering.-HRW