By Kamanthi Wickremasinghe.

A broken pair of rubber slippers kept on a display caught this writer’s eye as she walked into the ICES auditorium to witness an exhibition that explored Women’s Histories of Sex Work during the conflict. One may wonder as to what a pair of slippers possibly had to do at an exhibition that explored a topic that is seldom spoken about in Sri Lankan society. But the slippers had a story of their own. The trilingual display read how this pair of slippers was the first gift that a girl received from her boyfriend. But upon suspicion that she had had an affair with his friend, the boyfriend had not only beaten her with the slippers, but had eventually deserted her. The pair of slippers is her first memory of a pleasant relationship. Now this girl is a sex worker, but her boyfriend remains her first love.

Complexities of the commercial sex industry

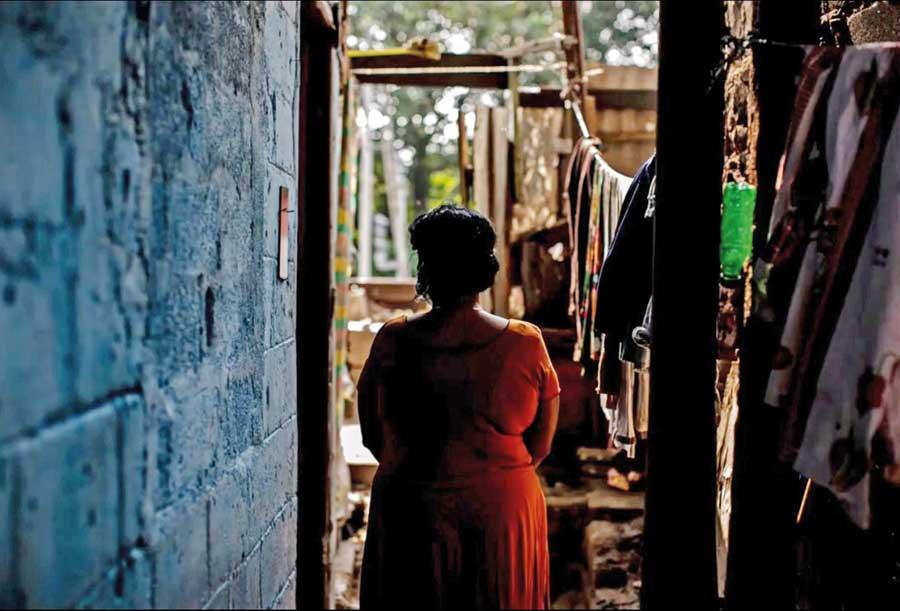

As such, stories of 35 women from across the country were documented by Radhika Hettiarachchi along with ‘the Grassrooted Trust’ where each story underscored the complexities of sex work during the conflict and how they extend beyond that historical moment to the present as women still engage in the commercial sex industry for their livelihood. Some stories highlighted sexual violence and sexual impunity during the conflict, some the impact of the conflict on women and their mental health, some accounts were about childhood trauma of rape and its consequences, some about empathy and kindness while others highlight how these women who are sole breadwinners of their families have taken control of the economic opportunities sex work offers.

“Nobody perceives this as a decent job. Everyone demeans it as indecent. But my main priority is to raise my children,” said one of the women who wished to remain anonymous while being feature on a video that captures the lives of sex workers. The Sex Workers and Allies South Asia (SWASA) network as per its peer-reviewed Status Report of Sex Workers (2023) states that the average sex worker is a woman between 26-50 years of age, who generally belongs to the urban poor, is a daily wage labourer, is directly affected by the war or is connected to the rural farming community.

“It is not about punishing these people for the only viable economic option that they have, but to make it safer and if they still choose to get out of it, to provide them ways in which they could get out of it without social recrimination”

– Paba Deshapriya of The Grassrooted Trust

Even though sex work is widespread in Sri Lanka sex workers are often arrested under the Vagrants Ordinance No. 4 of 1841. This archaic law allows police to arrest without warrant “every common prostitute wandering in the public street or highway, or in any place of public resort, and behaving in a riotous or indecent manner”. For the record sex work is criminalised in Sri Lanka.

Access to rights denied

The research identifies how sex workers who worked during and after the conflict are absent from the narratives of history. Their experiences are hidden behind social stigma, moral admonition and deliberate public silence. Therefore, this makes it difficult for this specific group of women to access compensation, recognition, accountability, justice and other economic opportunities afforded to survivors of a conflict in a setting of transitional justice. Women who shared their experiences during this project recollected how they had to remain low key in order to continue in their profession in a heavily securitised backdrop.

Lucrative profession

Many women showcased in the study have been placed in these circumstances due to poverty, war, displacement, the loss of a breadwinner or support system, compounded by the desperation of providing for their children/ families.

*Manjula, a mother of one who is in her sixties and is from Puttalam, recollected memories of a brutal past. She is from a migrant fisher family and at the age of 19 or 20 she had eloped with a fisherman. “I lived with him. But one day he packed his clothes and said he’s going to work and never returned. I was thrown into sex work and my clients were mostly army personnel and policemen. We were afraid of the uniforms because they were in control. Eventually I became pregnant and later found out that the father of my child was legally married and settled. My parents thought I was doing a job, but I was worried about my child. I used to work at a shop, but I only earned Rs. 400-700 daily. But through this type of work I can earn about Rs. 4000-6000 daily; hence I thought of continuing as a sex worker.”

Stories of women like Manjula elaborate on how the war had presented an opportunity for women to break out of their strictly defined social roles, giving them the opportunity and agency to find more lucrative livelihoods. These women view their choice to become sex workers as an act of courage.

“My parents thought I was doing a job, but I was worried about my child. I used to work at a shop, but I only earned Rs. 400-700 daily. But through this type of work I can earn about Rs. 4000-6000 daily; hence I thought of continuing as a sex worker,”

-Manjula

“Sex workers are doing a service”-*Kamala

*Kamala’s story reveals how some women engaged in sex work are courageous enough to emerge resilient and self-sufficient while enduring harassment and violence. Kamala, a mother of two and in her late forties is from a family of farmers from Hasalaka, Kandy. Having settled in Polonnaruwa many Sinhalese farmers couldn’t engage in farming as LTTE terrorists would abduct and kill them.“They would cut you down if they found that you were a Sinhalese,” recalled Kamala. “But my husband didn’t want to endure the trauma and decided to return to my village and work as a wage labourer instead,” she said.

But one day, Kamala’s husband who had said he would visit the town never returned. “We tried to find him, telegrammed everyone, but to date there is no trace of him. The government said that they would compensate widows, but I haven’t received anything. When I visited the police to lodge a complaint they took my number down and promised help. But after my husband disappeared I had an affair with a policeman. He would secretly visit me at home because back then my two children were small. But later on I found out that he was already a family man. Thereafter I stopped seeing him,” she said.

However Kamala recalled how she misunderstood people’s gestures. “Some shopkeepers gave me free food, dry rations and I thought they were doing that out of pity as I was widowed. But eventually they would ask me for sexual favours. Since I didn’t have money I engaged in sex work. But after sometime I gave up. People in my village respect me for who I am. I keep guard at my paddy field during the night,” she said.

Kamala said that people shouldn’t view sex workers in disgust. “Sex workers are doing a service. We give a man what he doesn’t get from home and he is happy at least momentarily. I managed to educate my children, built my own house and therefore I believe that I am courageous,” she added.

Building a context of sisterhood

For this research, the women were identified through regional associations of sex workers and peer-to-peer introductions if they were not part of any networks. They shared their histories because they wanted these stories to add weight to their journey towards societal acceptance and equality before the law. When asked how the researchers built the trust with the women to narrate their true life stories, the project’s lead researcher Hettiarachchi said that out of the 35 women about 20-22 of them were associated in some way with the SWASA network. “So they may be part of regional organisations or small groups from Moneragala, Puttalam etc., but they are part of a larger movement leading them towards asking for few different things. One such requirement is not to get arrested, another one is about dignity of labour and another need is to not be penalised by using healthcare such as forcing them to do blood tests etc, but to actually care for their wellbeing. This association allows them a kind of sisterhood, a kind of space to engage and get to know each other. They have shared their stories and have built a trust over a period of time and thereafter we documented these cases,” said Hettiarachchi.

A call to decriminalise sex work

The two-year research underscores how these women haven’t been given an opportunity to speak about violations they have experienced as whatever that happened during the war is outside public witness. “Women also think that this is part of their job and they don’t understand how much violence has permeated into their lives,” Hettiarachchi continued. “They don’t come forward from a justice point of view because sex work is often being look through a criminalised mindset. So the women themselves think they somewhat deserves this kind of violation and it’s something to be endured rather than challenged,” she said.

Although the research highlights stories from the past it connects to the present as these women still don’t have access to the justice system and because of the way the law is being applied to sex work. “Most women who were interviewed for this project are still engaged in sex work; hence this isn’t their past as yet. Therefore by linking them with the SWASA network they have been given a platform to amplify their voices, a way to interpret one another and build a context of sisterhood,” Hettiarachchi added.

Decolonising the law

The SWASA network is a movement comprising sex workers and their work in Sri Lanka has mainly been on decolonizing the legal system. The Vagrants Ordinance is a colonial law on vagrants to keep people away from white people and it is now being applied to sex workers as well. “Sex workers don’t need to be punished, they are doing all this to feed their children,” added Paba Deshapriya of The Grassrooted Trust. “Sometimes when their children find out about this they kick their mothers out. It is not about punishing these people for the only viable economic option that they have, but to make it safer and if they still choose to get out of it, to provide them ways in which they could get out of it without social recrimination,” said Deshapriya.

In 2020 when a brothel was raided and seven sex workers were produced before the court, the judge ruled that sex work is not an offence if they’re engaging in it for a living. “The Vagrants Ordinance includes words such as ‘indecent’ which were all drafted according to the Victorian eye,” said Deshapriya.

Deshapriya also spoke of how sex workers are being arrested while on their way home or while getting off the bus. “Our overall demand is to decriminalize sex work but until and unless the ordinance is repealed this demand will never see light of day,” said Deshapriya.

Sex workers’ demands

Sex workers now demand the authorities to not arrest them under the Vagrants ordinance. They say that nobody can ask them to plead guilty for soliciting sex work or for loitering or being indecent because they are doing a job. “The findings of the status report where we interviewed over 300 women indicate that over 50% of women are asked to plead guilty by either their lawyers or law enforcement officers. This way they carry a criminal record, but they were actually not loitering or soliciting or being indecent, but were standing on the road in sex work. The police for example need to accept that sex work is work and not go about beating sex workers,” said Deshapriya.

Sex workers are excluded from society to a point that sometimes they are reluctant to even obtain an ID for themselves. The status report indicates that 70% of them haven’t applied to obtain these documents. “They don’t go to the grama niladhari to inquire about these matters. The small percentage of women who have applied for these documents admit that they have been asked for sexual favors in order to be on the list! They don’t get birth certificates for their children because they don’t have a husband. Once they say they don’t have a husband they have to disclose what they do. Thereafter they cannot send their children to school and it’s a cycle of violence because of the stigma around sex work. As a result a lot of their rights are completely violated,” said Deshapriya.

The workers also recognize that their work is unsafe. “The status report lists out a number of threats which vary from the, being killed to raped, gang-rated, getting robbed, their children seeing them, parents walking into the room or to the house. Most of the time their workplace is not safe for them,” explained Deshapriya.

Accepting sex work as another form of labour

In 2017, the CEDAW committee in its concluding observations on Sri Lanka said that ‘faced with the constant threat of criminal action, sex workers in Sri Lanka are unable to benefit from Sri Lanka’s labour framework such as demanding safe and dignified working conditions or obtain social security benefits.’

When asked if sex workers are willing to change their profession Deshapriya said that it had been a longstanding argument. “For them, this is the only lucrative and viable mode of income. There have been various projects done to provide sex workers with alternative jobs, but they may not have skills to do other jobs,” said Deshapriya.

Many don’t take to sex work as a choice, but do out of necessity. “But when you consent to have sex work it doesn’t mean your consent should be violated. Their men may be disabled or have abandoned women with children. Sex work is therefore a form of labour; a form of work,” said Deshapriya.

However, going forward, the lead researchers of this project plan to work locally, with grama niladhari officers and most importantly lawyers who can accompany sex workers to the government officers or to the police. “However there’s a gap to be bridged and a lot of sensitization needs to happen at the ground level because that is where most challenges are. Hence our next step is to have these conversations with the lawyers,” Deshapriya concluded.

As this writer walked past a camouflage T-shirt and a baby’s bonnet kept on display, these items further highlighted the emotional trauma endured by sex workers. The camouflage T-shirt is a memoir that a mother keeps to remind her son that he had a father ; “He gave me a child but not his name for my son’s birth certificate,” the display read, while the baby’s bonnet is the only cherished memory of a sex worker who gave birth to a stillborn child.

(Names of women have been withheld under conditions of privacy)