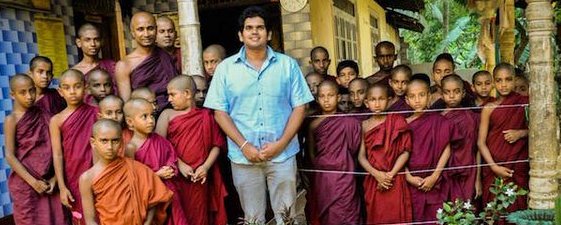

( President Sirisena’s son post for photographs with young monks)

Introduction:

Almost seven years have lapsed since the end of the war, yet Sri Lanka continues to remain a deeply divided society. Empirical evidence from the four waves of the ‘Democracy in post-war Sri Lanka’ public opinion survey conducted by Social Indicator (SI), the survey research arm of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), corroborates this ground reality: Sri Lankans are polarised along ethnic lines on key questions related to governance, and the task of promoting reconciliation between the island’s diverse communities has been identified by the current administration as a key priority. A special Presidential Task Force on Reconciliation, which subsequently metamorphosed into the Office for National Unity and Reconciliation (ONUR) was thus appointed in March 2015, with a specific mandate “to lead, facilitate, support and coordinate matters related to national unity and reconciliation in Sri Lanka”.

Divisive nationalist posturing from the country’s main ethnic communities has presented the singular most formidable challenge to reconciliation, social cohesion, and the vision of creating a united Sri Lanka.

This report examines the phenomenon of ethno-nationalism, broadly defined as “the extreme political expression of ethnicity”, among the island’s largest ethno-religious group – the Sinhala Buddhist community, and the dynamics of Sinhala-Buddhist ethno-nationalism in the post-war context. Contrary to some interpretations that ethnicity has lost its power as a tool for political mobilisation, this report contends that Sinhala-Buddhist ethno-nationalism remains a highly potent force. Nationalistic fervour appeared to be on a downward trajectory following the January 2015 presidential election in which Maithripala Sirisena won campaigning on an anti-corruption platform which pulled together a number of divergent political forces. However, the growing disenchantment in the Sinhala-Buddhist community on many fronts, their burgeoning economic woes in particular, at least in part has made it easier for nationalistic political posturing to re-capture its lost appeal.

This report also argues that while the vast majority of Sinhala Buddhists embrace rationalistic values and are amenable to sharing power with the minorities, nationalistic forces within the community continue to subsume moderate voices. As a direct result of their dominance and the centre’s apprehensions of triggering an extremist backlash, arriving at a sustainable political solution to the country’s ethnic question will remain a contentious issue. Therefore, although the government has accorded priority to ‘reconciliation’ as a policy objective, a meaningful reconciliation process which – most critically – includes the formulation of an inclusive political system whereby minorities will have an equitable stake in governance will be extremely challenging in view of this reality.

The conclusion:

There is little doubt that the biggest challenge to Sri Lanka’s reconciliation agenda comes from nationalists on all sides of the divide. The difficulty lies in the fact that there can be serious resistance from nationalists to evolving a meaningful power-sharing arrangement as a key component of the reconciliation process. Ethno-nationalistic rhetoric was strongly invoked during both major elections of 2015, but it was unable to harness adequate support to ensure electoral victory for the nationalist camp because other pressing issues impelled a significant proportion of the Sinhala-Buddhist population to vote for a change in the country’s political leadership.

Sinhala-Buddhist ethno-nationalism, the particular focus of this report, was on a general downward trajectory following the 2015 presidential election driven in large part by the discourse on democracy which was activated in the run-up to the election and thereafter.

Nevertheless, it remains a very potent force which could be used to stir communal discord as the context changes. The growing disenchantment in the Sinhala-Buddhist community on many fronts, their economic and cultural insecurity in particular, at least in part has made it easier for nationalistic political posturing to re-capture its lost appeal. The popularity of ‘Sinha-Le’ campaign, which appears to be politically-backed and well-organised evinces ethno-nationalism’s continued power as a tool to mobilise insecure masses.

In this connection it is important to note that the Government’s decision to withdraw the Penal Code Amendment Bill to render hate speech a crime punishable by a two-year prison term is welcome, as it could have been potentially dangerous in view of the fact that successive governments have used such provisions to selectively target political opponents. The necessary legal framework is already in line with international standards, and what is required is to ensure the uniform application of existing laws.90 The law enforcement agencies should implement existing laws pertaining to hate speech as defined in the Penal Code and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and guarantee a climate in which all religious communities can practice their faith without fear.

It the Constitution which accords Buddhism the foremost place. No doubt all religions should both be viewed and treated equally and that a secular state is indeed the ideal, but to attempt to remove this clause at this juncture would in all likelihood lead to a backlash and scuttle the reform process.

The success of the reconciliation process will be contingent upon the government’s ability to retain the confidence and support of the Sinhala community as much as all other communities. It is important to respect national consciousness, not to dismiss or to deny it. Concerns of the Sinhala-Buddhist population have to be taken seriously, in particular the fear that power-sharing will lead to Sri Lanka’s disintegration and poses a threat to Buddhism. Any process that does not address these concerns will certainly not be sustainable. If extremists are not included in the process of determining the country’s future, there is the danger of them becoming spoilers.

Therefore, the strategy should be to further expand the middle by involving the extremists in a spirit of transparency and consultation, and to foster a conception of Sri Lanka from an essentially Sinhala-Buddhist state, to a multi-religious, multi-ethnic, pluralistic society.

Possibly the best example of this middle ground was found in the rainbow coalition that propelled Maithripala Sirisena to the presidency. One of its key movers, the late Ven. showed how a Buddhist religious leader espousing core Buddhist values such as compassion and universalism can take Buddhist concerns seriously and yet act as a unifying force for all communities. The opening created on 08 January 2015 for civic nationalism to supersede the confines of ethnic nationalism should be fully utilised by the current political leadership and civil society groups to broaden the middle ground to push forward the reconciliation and development agenda.

From a report by Centre for Policy Alternatives