These are a few thoughts on the recently concluded elections in Sri Lanka. Elections can be studied in various ways. The underlying interest in these comments is the state formation process in Sri Lanka. It is an attempt to place the results of the recently concluded presidential and parliamentary elections in the context of state formation in post-1977 Sri Lanka.

States, like any other social phenomena, are a product of history. There is nothing natural about states. They have undergone changes in the past, are changing at present and are likely to do so in the future. These perspectives are lost in the usual treatment of the state, where it is treated as a concrete self-contained entity that has attained a final status. Of course, those who control the state and their ideologues always try to convey this notion. A whole paraphernalia of ideas and symbols are developed to convey the eternal character of the state. In contrast to this, when studying the state, it is always necessary to maintain a perspective of change, and therefore state formation is the more appropriate approach. This also means the primacy of historical approaches in studying the state.

[title]States as state-society complexes[/title]

States are seen here as state-society complexes. State-society relations are maintained through coercion and consent. State formation involves developing mechanisms to control territory and manage state-society relations. The institutional structure of the state, sometimes called the administrative structure of the state, is one such mechanism. It collects information and carries out various tasks to ensure control over territory and people. The security apparatus, which is based on a notion of state security, is the other obvious mechanism.

This does not mean all mechanisms used to control territory and people are coercive. For example, states implement many social policies to manage state-society relations. Those states that are able to manage state-society relations primarily through consent have a greater capacity to fulfil their role towards citizens in an effective manner. They have a greater degree of legitimacy, and are strong.

[title]States identities[/title]

States also have identities. State formation involves the construction of an identity of the state. Some states have an identity that has a greater degree of legitimacy with diverse identity groups in society. However, in the history of state formation, bringing together social groups with diverse ethnic and religious identities into a single polity and constructing a state that has legitimacy with all identity groups, has not been an easy process. This becomes even more complicated if identities are linked with territory. This can challenge the territorial control of a state.

In their history, states have various methods of choosing the political elite who control the state. Elections are one such process. They are also a mechanism of managing state-society relations. Elections are a choice given to a certain section of the population who are eligible to vote within a set of historically constituted institutions. They transfer votes to political outcomes and choose a political elite whose power is legitimised. By this process the political elite secure control over the state. Two aspects are important when analysing electoral politics and state formation – elite political struggles to secure control of the state and voter behaviour.

Electoral institutions operate in a particular society with its own divisions, ideas and identities that have evolved in history. It produces contradictory outcomes that have an impact on the state formation process. Sometimes electoral politics help to produce a political leadership that has legitimacy with all sections of the population and also constructs what can be called a national political space. But there are states where this does not happen. Electoral politics can undermine formation of a unified state in such situations.

[title]State formation in an international context[/title]

State formation always has to be studied in an international context, taking into account systems of political authority that lie outside its territory. An approach that confines itself to the juridical entity of a state is based on a notion of the state as a self-contained static entity. The study of state formation should be a study of the history of individual states in a global context. States are formed and exist in a context of an international system of states. The other dimension of this international context is global capitalism. States have to secure resources for their functioning in a world dominated by capitalism. The international system changes over time both politically and economically which in turn has an impact on state formation.

The most important thing to note is that all these processes behind state formation are always contested. There are always disagreements, struggles and conflicts around these processes of state formation. Some of the contradictions can reach the level of armed violence. Historically the state formation process in general has not been a peaceful one. Coercion and violence have played a significant role in the formation and maintenance of states.

[title]Post-1977 state formation in Sri Lanka[/title]

State formation in post-1977 Sri Lanka has to take into account two key processes. First, the demand for a separate state by the Tamil minority. This was due to a failure in post-colonial state formation process in a multi-ethnic society. Post-colonial electoral politics contributed to this process. This has been the main focus of much of the literature around Sri Lanka’s conflict.

The second dimension of state formation was managing relations with the Sinhala majority in the context of a new period of capitalist transition in 1977. New policies gave importance to markets, private sector and a greater degree of openness to global capitalism. Capitalist development is a politico-economic process. This differs from the orthodox approach, which begins by demarcating a sphere called the economy from society and politics. Capitalist development involves changing institutions or the ‘rules of the game’, so that markets become the primary mechanism for resource allocation and ideologically legitimising these changes. When these efforts are successful, they become ideas that seem to be natural and part of common sense, thereby creating a hegemony. This politics of capitalist transition has to manage relations with various social groups in society, which in turn have an impact on state-society relations and state formation process. How this process takes place in a specific historical context depends on the political agency of the ruling elite, their ideological orientation and the role of the state. However, the politics of this process is not always peaceful. The political elite who control the state can use the coercive power of the state to take forward the process of capitalist development.

[title]State formation & Sinhala nationalism[/title]

The post 1977 state formation had to manage relations with the Sinhala majority in the context of the new period of capitalist transition. It is not that other ethnic groups were not affected by this process. But political opposition to transformation of the economy was located within the Sinhala majority. Within the Sinhala majority, socio-economic grievances due to the spread of markets could easily combine with Sinhala nationalism to produce a formidable opposition. In addition, the voting behaviour of the Sinhala electorate was crucial in choosing the ruling regime through elections.

[title]Strong presidency[/title]

The politics of managing relations with the Sinhala majority in the new period of capitalist transition changed Sri Lankan electoral politics significantly. A key political development in this process was the introduction of the presidency through the 1978 constitution. J.R. Jayawardena, who led UNP to an electoral victory in the 1977 general election advocated the need for a strong presidency way back in 1966, when he was a minister in the 1965-70 UNP government. His argument was that there was a need for a strong president, that is independent of the parliament, to carry out unpopular economic reforms. It was introduced in 1978 using the majority that the UNP had in parliament. In other words, it was introduced using political power wielded by a section of the political elite. There was hardly any consultation within the political elite, let alone the wider public. The main purpose was controlling the parliament, the main channel of political pressure from the Sinhala majority, through a directly elected president.

Once created the presidency, and the power it enjoyed, became the most sought-after office for the political elite. It became the focus of political struggles of the elite. It also strengthened the idea of the need for a state with strong central control. The idea of a strong centre attracted support from both Sinhala nationalists and those who looked towards capitalist growth as a basic requirement for social progress.

The other important aspect to remember is that elections held in the post-1977 period were elections in a fractured state affected by violence. Voting rates were relatively low especially in the Tamil dominated North Province and Batticaloa District. It was similar in other Eastern Province districts. This is an indication that these were not elections in a state with territorial integrity. The inability to have elections as usual was only one indicator of the fractured nature of the state. During this period the Sri Lankan state could not carry out several other exercises of data collection in these areas, an indicator of a state not having control over its territory.

[title]Post-war electoral politics[/title]

If we look at state formation as a historical process, it is necessary to look at the period after the defeat of the LTTE and restoring central control over the war-affected area as a product of the period of war and how it ended. Post-war state has its own contradiction. War has ended, but challenge of political reforms for a state that has legitimacy with diverse identity groups remain unresolved. In some areas this issue has become worse. In addition, after forty years of the new period of capitalist transition the Sinhala nationalist state presiding over a society that is showing a high degree of economic inequality. This generates its own contradictions. The state is also facing numerous issues in a world which is now dominated by global capitalism and new forms of inter-state conflicts.

This means we need to question the basic assumptions of both Sinhala nationalists and followers of liberal peace. Both base their arguments on a vision that assumes that Sri Lanka has gone through a bad period of violence, and now that is over, we need to focus on more other issues. For Sinhala nationalists and apologists of capitalism, we need to end all this talk of ethnic groups and focus on economic growth and building a strong state. For liberals, we have to focus on transitional justice, reconciliation and promoting liberal democracy. Of course, this group also accepts capitalism uncritically. The other prop of liberals is the belief in an ‘international community’ without taking into account how this neo-liberal construction is facing problems globally at present.

[title]The collapse of the liberal peace strategy[/title]

It was the collapse of the liberal peace strategy – of trying to stabilise the state with direct negotiations with the LTTE and move the economy to a new stage with international support -that paved the way for Mahinda Rajapakse to emerge as a new leader of Sinhala nationalist politics. By this time the leaders of the two main political formations that has ruled the country – the UNP and SLFP – have absorbed the broad ideology of liberal peace that included a notion of direct negotiations with the LTTE with international support. Hence the collapse of the liberal peace strategy was bound to have a significant impact on the politics of the Sinhalese.

Rajapakse consolidated his position with victory in the 2005 presidential election by defeating the UNP candidate Wickremasinghe. But it was an election in a fractured state. Presidential elections choose the head of the state of centralised Sinhala nationalised state. The enthusiasm for this electoral exercise, reflected in the voting rates, in the Tamil dominated Northern compared to Sinhala dominated areas. In 2005 presidential election was only 9.9 per cent of the registered vote. Even in the Tamil-dominated Batticaloa District in Eastern Province, the voting rate was 48.5 per cent well below national average. Additional factor in this election was the boycott of elections organised by the LTTE. This had an impact on voting rates in war-affected parts of North and East. Rajapakse won with a very narrow margin. The low voting rate in the Northern and Eastern Provinces certainly contributed to Wickremasinghe’s defeat.

Rajapakse’s role in giving political leadership to destroying the LTTE and bringing back control of the war-affected area to the central state, certainly consolidated his position as the new leader of Sinhala nationalist politics. He made use of this new position to strengthen his electoral position. He called an early presidential election, which was held in January 2010. The leader of the UNP did not contest the presidential election, largely because he was not sure of his popularity within the Sinhala majority after giving political leadership to the collapsed liberal peace. Instead the UNP supported Sarath Fonseka, the commander of the army who led the military campaign against the LTTE. This means that in the first presidential election after consolidation of the territory, both main candidates were directly linked to the military victory. One of them was backed by the UNP which led the liberal peace strategy.

Rajapakse easily won the election. Voting rates in the war affected Northern Province improved from the 2005 election. But it was only 30.2 per cent. In the Batticaloa District it was 64.8 per cent. The fact that both candidates trying to become president and head of the centralised state were directly associated with military operations could not have made this election very attractive especially in the Tamil dominated areas of North and East.

The General Election 2010

A general election followed in April 2010. The Rajapakse-led United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) secured 144 seats in a parliament of 225 members. This was just six members short of a two-thirds majority. Voting rates, especially in the war-affected Northern Province, continued to remain low, despite the fact this was an election where voters were choosing representatives for their own areas and parties that got elected had ethnic identities.

Keeping with the trend within the political elite, where controlling the state through a strong presidency Rajapakse took steps to strengthen the presidency and his control over it. This was done by passing the 18th amendment to the constitution with a two-thirds majority. Although he did not have a two0third majority in the parliament, he secured this because of a number UNP members crossing over to the government side. This is an example of shifting political allegiances under political institutions established through the 1978 constitution. Within patronage politics of Sri Lanka, where politics is dominated by the objective of ensuring resources and privileges, a common phenomenon is MPs gravitating towards the prevailing centre of power.

With these events, the Rajapakse family became the newest member of the political families that Sri Lankan electoral politics has produced. This is not a new phenomenon in Sri Lankan politics and has received the attention of political scientists. But what was interesting was despite Rajapakse’s effort to consolidate his power within the post-war state, he was defeated in the presidential election held on 8 January 2015. In other words, despite the military victory and consolidating the territory of the Sinhala nationalist state, Rajapakse, who was hailed as the saviour of the Sinhala nation by his supporters, was defeated in a presidential election six years later. For many reasons, this election is interesting when trying to understand the second dimension of elections and state formation in post-war Sri Lanka – voter behaviour.

The candidate who opposed Rajapakse in 2015 was Maithripala Sirisena. He crossed over to the opposition and contested as a candidate for the New Democratic Front with the support of the UNP. This type of cross overs and political intrigues within political elites is not unusual. There have been several occasions in the past when a powerful regime in power was brought down by defection of senior members from its ranks. The more important fact for the politics of the Sinhalese was that the UNP leader Wickremasinghe could not face the electorate as the presidential candidate. Almost ten years after the collapse of his liberal peace strategy and even with the usual tendency of the incumbent regime becoming unpopular over time Wickremasinghe could not face the election in 2015 as a presidential candidate.

Sirisena defeated Rajapakse securing 51.3 per cent of valid votes, compared to Rajapakse’s, 47.6 per cent. The most important aspect to note from a state formation perspective was the improvement of voting rates in the war-affected areas. In the Northern Province it increased to 68.3 per cent and Batticaloa District 71.0 per cent. Although still below the all island rate of 81.5 per cent these were signs that a key factor that legitimises the Sri Lankan state, participation in elections. was improving in the war-affected areas. The fact that this was a presidential election, where a head of state is chosen when the entire island is a single electorate, makes it even more important.

Two factors in voter behaviour explain the electoral outcome. First, the increase in voting rates in war affected areas and Maithiripala Sirisena gaining a higher proportion of votes in these areas. The second factor was Rajapakse losing his support outside North and East. Majority of electoral districts in these areas are dominated by the Sinhala majority. In the 2015 presidential election, Mahinda Rajapakse’s share of valid votes was lower than what he received in 2010 in all electoral districts of this area. When it comes to the share of valid votes in each electoral district Rajapakse’s share was lower in Colombo, Kandy, Nuwara Eliya, Polonnaruwa and Ratnapura electoral districts compared to what Sirisena received. This means between 2010 and 2015 presidential elections there was a shift away from the Rajapakse camp in some Sinhala-dominated areas. Therefore, Maithripala Sirisena did not win only because of the minority vote. It was a combination of maintaining a Sinhala voter base and securing the support of minorities. When the presidential system was established, and the entire country became the unit for electing the president, there was always speculation on how one of the major parties could win this election with a combination of its own voter base and the minority vote. But this could not be tested because voting rates in the Northern and Eastern Provinces were affected by the war. In other words, it was a vote in a fractured state. With the end of the war, and revival of voting rates in the war-affected areas this seems to have happened.

Rajapakse’s loss in 2015, even after he gave political leadership to consolidate the territory of the Sinhala nationalist state, forces us to question single factor ethnic based explanations of electoral behaviour of the Sinhalese. It is not that ethnicity was not a factor. But the issue is single factor explanation. Generally single factor in electoral behaviour is not tenable. There are other reasons why Rajapakse lost his popularity with at least a section of the Sinhalese. In addition to the unpopularity of the style of governance of the Rajapakse regime, the regimes economic strategy, which relied heavily on infrastructure development, did not have any new initiatives in social policies. Let us not forget that 2008 was a crisis year for global capitalism. This would have had an impact on an economy integrated to global capitalism. Economic policies of the regime did not have a response to this situation.

In the general election that followed in August 2015, a coalition came together under the name United Front for Good Governance (UNFGG) and won the elections. In a parliament of 225, the UNFGG secured 106 seats and UPFA 95. The more important development was the improvement in the voting rate in the Northern Province. The voting rate of 64.9 per cent was the highest in a general election after the introduction of the PR system. Although it was not as high as in the 1977 general election, the last election before voting rates were affected by the war, this marked a revival of the electoral process in a Tamil dominated Northern Province, the heartland of Tamil nationalist politics and separatism.

Both presidential and general election results in 2015 gave some hope of a possible improvement in tackling political reforms towards a legitimate multi-ethnic state. But what dominated was a struggle for power within the political elite who led the regime. As was the case in the entire post – 1977 period, the struggle over presidential power was the key issue. Although the UNP supported Sirisena in becoming the president, pretty soon it was clear that there were two centres of power in the new regime, one led by the president and the other the prime minister. There was disagreement on key issues, such as economic policies and the security strategy. The UNP political strategy was to pass the 19th amendment to the constitution, which reduced the power of the president, and to secure control over main areas, such as economy, foreign policy and defence.

D,isagreements within the regime came into the open in October 2018, when the president suddenly dismissed the prime minister from the UNP and replaced him with Rajapakse. But this was challenged in the Supreme Court on the basis of the provisions of the 19th amendment. The Supreme Court decided that the move by the president was against the provisions of the 19th amendment. Thus, the UNP strategy of managing the president through the 19th Amendment worked. However, these legal means could not deal with issues arising from the struggle for power within the political elite.

The divisions within the regime manifested in a disastrous manner just a few months before the presidential election due in December 2019. This was how the regime managed or did not manage security issues around the bomb attacks on churches on Easter Sunday in April 2019. It was stark manifestation of divisions within the regime and its inability to ensure a basic function of a state – to provide security. This brought back a deep sense of insecurity in many sections of the society that had experienced such events for a long period.

In the December 2019 presidential election, Rajapakse led Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna came back to power with 52.3 per cent of valid votes. The winner was Gotabaya Rajapkse, the brother of Mahinda Rajapakse. This election was significant within elite political struggles for several reasons. First, the process that began with Mahinda Rajapakse becoming a new leader of Sinhala nationalist politics has produced a new political party known as the SLPP. Second, in the process of choosing the presidential candidate from the UNP, the leadership of Wickremasinghe, who could not be a presidential candidate after the collapse of liberal peace, was challenged within the party.

What happened in the 2019 presidential election compared to 2015 results, can be explained by the inability of political parties linked to the regime elected in 2015, to retain its Sinhala electoral base. Sajith Premadasa, who had the support of these parties, lost in all Sinhala-dominated electoral districts in areas not affected by the war. One obvious explanation of this is the persistence of nationalist politics within the Sinhala majority. But this alone might not be enough. Another factor were the divisions and dysfunctional nature of the regime. Finally, once again the UNP’s blind adherence to neoliberal economic policies failed to provide any answer to socio-economic problems in a society affected by more than 40 years of liberal economic policies. Although Premadasa, like his father during the 1989 elections, tried to bridge this gap by making many promises on socio-economic issues, it did not work.

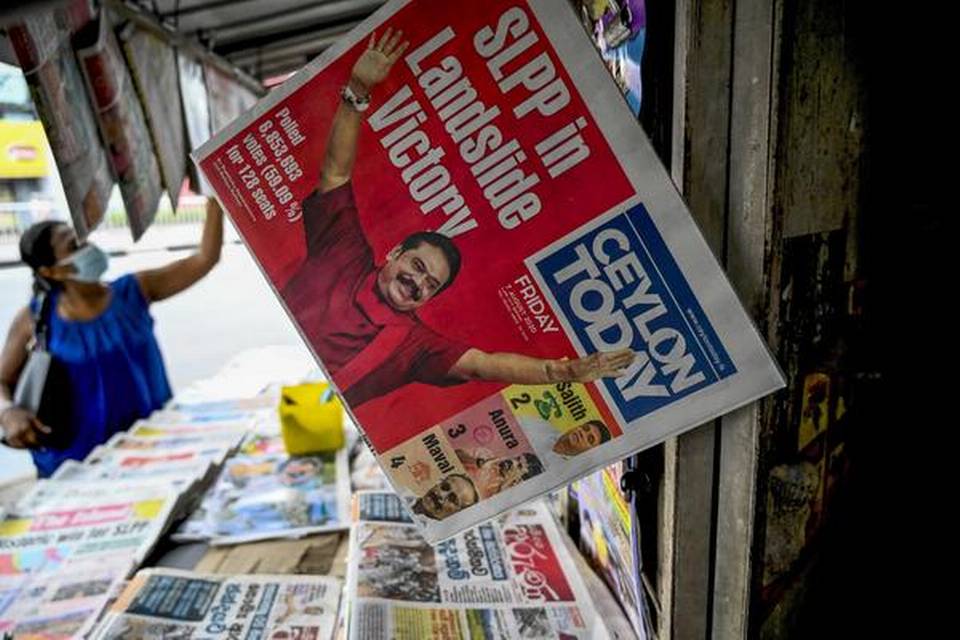

Two factors stand out from the just concluded general election. On one hand results are similar to results of 2010 general election. In 2010 general UPFA secured 144 members in a parliament of 225 members. In 2019 SLPP won 145. Once again, this result will be used to enhance the power of the presidency that has characterised the post 1977 state formation process. Second, this election also could signify a transformation of the political party system that depends on the support of the Sinhala majority. On one hand the UNP is divided. On the other side the SLFP presence in parliament is insignificant. Rajapakse’s SLPP has certainly been the main beneficiary of what has happened to UNP and SLFP. Finally, with14 parties represented in parliament this is the most diverse parliament under PR.

(22nd September 2020)