Image courtesy of Hiaml South Asia.

Frances Harrison.

“Why I confronted the former president with the Batalanda Commission report during his Al Jazeera interview – and why Sri Lanka must face up to the torture, disappearances, and human rights abuses of the 1980s JVP insurrection.”

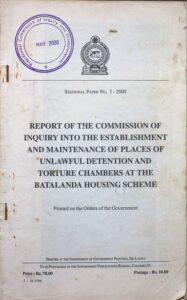

WHEN WE STARTED getting messages that the International Truth and Justice Project (ITJP) website was not working, in the wake of an Al Jazeera interview with the former Sri Lankan president Ranil Wickremesinghe aired on 6 March, I assumed the site had been hacked or attacked. It did not occur to me that our server had been overwhelmed by the sheer volume of traffic to the site. Suddenly, a quarter of a century after it had been released, everyone wanted to read the “Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Establishment and Maintenance of Places of Unlawful Detention and Torture Chambers at the Batalanda Housing Scheme” – better known as the Batalanda Commission report.

I went to Sri Lanka as a BBC correspondent in late 2000, and I am ashamed to say that I, like so many others, had never heard about the report then; there were just occasional whispers about something from a previous time. Nobody mentioned the Presidential Commission of Inquiry. The silence around the wave of disappearances and killings in the South of Sri Lanka during an uprising by the leftist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) in the late 1980s was pervasive.

It was only two decades later, while investigating alleged perpetrators in the security forces, that I finally learned about the report. It was available online only in Sinhala; eventually, a friend who knew I was searching for the English version unearthed it from a box of old documents. Like so many historic human rights investigations in Sri Lanka, the report had been suppressed. It was remarkable that the Batalanda Commission report had never been published at all, unlike many other inquiry reports.

It was only two decades later, while investigating alleged perpetrators in the security forces, that I finally learned about the report. It was available online only in Sinhala; eventually, a friend who knew I was searching for the English version unearthed it from a box of old documents. Like so many historic human rights investigations in Sri Lanka, the report had been suppressed. It was remarkable that the Batalanda Commission report had never been published at all, unlike many other inquiry reports.

The Al Jazeera interview

In the Al Jazeera interview, the journalist Mehdi Hasan challenged Wickremesinghe over his violent response to the people’s protest movement that had forced the Rajapaksa clan out of power in 2022. Wickremesinghe became president in the aftermath, in place of Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Hasan also asked him about the endless delays in justice for the victims of the Sri Lankan Civil War, his failures regarding the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings, and whether he did enough to hold the Rajapaksa family to account for Sri Lanka’s terrible economic crisis. When Al Jazeera asked me to join a panel as part of the conversation, I had sent the Batalanda report, so I knew it might also come up in the questions. The producers instructed us to come to the recording with just pen and paper – but some psychic instinct told me to also take a copy of the front page of the report, folded up inside my notebook.

In the late 1980s and into 1990, the period relevant to the commission of inquiry, Wickremesinghe was first Sri Lanka’s minister of youth and employment, and later the minister of industries and science. He was also the elected representative in parliament for the Biyagama electorate, which today falls under the electoral district of Gampaha. The village of Batalanda, where the Batalanda Housing Scheme is located, fell within Wickremesinghe’s constituency.

Key allegation against Wikckremasinghe

The report’s key allegation is that Wickremesinghe must have been aware of torture and illegal detention perpetrated by the police in the Batalanda housing complex – where he maintained a bungalow with staff and stayed overnight on occasion.

The housing complex had been tied to the State Fertiliser Manufacturing Corporation. Wickremesinghe had directed that buildings in the housing complex be given over for use by the Kelaniya police division. There is conclusive evidence that, between 1988 and 1990, some of the houses were used to illegally detain and torture suspected JVP cadres. There were also meetings held at the complex in connection with maintaining places of unlawful detention and torture chambers there. During these meetings, Wickremesinghe had given directions related to the police’s conduct of anti-subversive activity. The commission held that he did not have any legal authority to give such directions.

A photograph of the cover page of an official report titled ‘Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Establishment and Maintenance of Places of Unlawful Detention and Torture Chambers at the Batalanda Housing Scheme.’ At the top, there is a Sri Lankan government emblem and a circular stamp that reads ‘Presidential Commission of Inquiry into Disappearances’ with the date ‘MAR 2000.’ The report is labeled as ‘Sessional Paper No. I – 2000’ and states that it was printed on government orders.

A photograph of the cover page of an official report titled ‘Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Establishment and Maintenance of Places of Unlawful Detention and Torture Chambers at the Batalanda Housing Scheme.’ At the top, there is a Sri Lankan government emblem and a circular stamp that reads ‘Presidential Commission of Inquiry into Disappearances’ with the date ‘MAR 2000.’ The report is labeled as ‘Sessional Paper No. I – 2000’ and states that it was printed on government orders.

The front page of the Batalanda Commission report. “Where is that commission?” Ranil Wickremesinghe said in an Al Jazeera interview where he questioned the report’s existence. “Has that commission report been tabled [in parliament]?”ITJP

I had assumed Wickremesinghe would defend himself by alleging that Chandrika Kumaratunga, who convened the commission as president in 1995, had been politically motivated. But when confronted with how a government inquiry had named him the “main architect” of securing the Batalanda housing complex for detention and torture, Wickremesinghe just said, “Where is the report?” He continued in this vein: “Where is that commission? Has that commission report been tabled [in parliament]?”

Never did I think he would just deny the report’s existence, and that I would have to wave its cover in front of him. Nor did I imagine that he would then convene a press conference in Colombo to denounce me as a Tamil Tiger – and this for raising the issue of human rights violations against mostly Sinhalese individuals, who were the main victims of Batalanda.

Maybe equally surprising was that Wickremesinghe would be so catastrophically unprepared for an interviewer known for his pacey and probing style. He later alleged that the editing of the interview was unfavorable to him. Believe me, the unedited version was much worse. Wickremesinghe was allowed to choose one member of the panel, but his candidate was unable to help him.

Wickremasinghe was unprepared

The recording was held before a live audience in London, where Wickremesinghe, as a Sri Lankan politician, should have expected Tamils seeking justice to be in attendance. Throughout the 26-year civil war, there was an exodus of Tamils fleeing violence and persecution in Sri Lanka. Many sought refuge in the United Kingdom and other Western countries. In front of a young female survivor who fled from Mullivaikkal – the coastal stretch in northern Sri Lanka where civilians were bombed, shelled, and starved in the final stages of the war in 2009 – Wickremesinghe could not make up his mind whether hospitals in the war zone had been bombed and shelled. The United Nations has been very clear that every makeshift hospital and clinic in the area was attacked by Sri Lankan forces in 2009.

Wickremesinghe gave the impression that he had never bothered to study the allegations of human rights violations against his country. This was even though he oversaw an internationally backed transitional justice initiative in 2015, and in the 16 years since the end of the war, he had been the prime minister of Sri Lanka four times and president once. In a portion of the interview that was edited out and never aired, he seemed to think that I was responsible for the estimated 40,000 civilians killed in the final phase of the war, even though it is widely known that a panel of UN experts arrived at this number.

And yet, even seemingly lacking the most basic information about alleged atrocities, Wickremesinghe was quite sure that the generals in charge of the war – men like Shavendra Silva, named and shamed by the UN and the European Union, blacklisted by the US government for his alleged role in extrajudicial killings – have nothing to answer for. As president, Wickremesinghe re-appointed Silva as Sri Lanka’s chief of defense staff. That was in 2024, before he was voted out of office and replaced with Anura Kumara Dissanayake – Sri Lanka’s first president from the JVP.

The Al Jazeera interview set off a lot of discussion about the Batalanda report. It has been disturbing to watch the noise on social media, especially as things have descended into personal attacks, chaotic “whataboutism” and vicious ethnic abuse between Sinhalese and Tamils. It is good that there is fresh scrutiny of the violence of the JVP uprising and its repression by the government, but this should start with a reading of the historical documents of that era, as well as with close attention to surviving victims and those who have steadfastly worked to support them over many decades.

The hope 35 years after the end of the second JVP insurrection (an earlier attempt, in 1971, was also crushed) is that all the investigation documents will be made public. The ITJP and the public still only have access to the main part of the Batalanda Commission report, comprising 167 pages – but the whole report, with annexes and testimony, runs to 6780 pages over 28 volumes.

In the wake of Wickremesinghe’s question about whether the report had ever been tabled in parliament, it finally was. Bimal Rathnayake, the leader of the house and a member of the JVP, took that official step in mid-March. During the session, it was announced that the report would be handed over to the attorney general and that Dissanayake would appoint a committee to look into further action.

As Rathnayake noted, “The astounding fact is that not one of the 750 printed copies was forwarded to the Attorney General. Therefore, those who called for this report not only failed to implement the recommendations but merely used it as a political tool during elections.” He said there will be a two-day debate on the report, and that it will be printed afresh for public release in Sinhala, Tamil, and English. The demand now should be that the report be published in its absolute entirety so that we can see what else it contains.

Many questions remain even after these promises. Who will be on the new committee, how independent will it be, what will its mandate look like, and why it is only looking at one torture site from the time of the second JVP uprising and not the many others long known to also have existed back then? Will the full report, including testimony from key witnesses like Vincent Fernando, the caretaker of Wickeremesinghe’s residence at the Batalanda complex at the time, be published immediately? Will witnesses still alive today – including Merrill Guneratne, formerly a top police official, and Sudath Chandrasekera, a long-time aide to Wickremesinghe – be interviewed again?

The risk of Batalanda report

The risk is that Batalanda may yet again become a tool to penalise political opponents, without justice for its victims.

A DISUSED COMPLEX in the vicinity of Kelaniya, a suburb to the north of Colombo, the Batalanda Housing Scheme was attached to the State Fertiliser Corporation. When the government decided to liquidate the Fertiliser Corporation Batalanda came under the purview of the minister of industries and science – Wickremesinghe at the time. According to the report, he allocated some vacant units in a corner of the site, described as a “mini complex”, to the Counter Subversive Unit (CSU) of the Kelaniya police. From March 1983 to August 1994, he also had a house in the same corner of the complex. A caretaker of the residence said Wickremesinghe frequented it from 1988 to 1990, staying overnight on most occasions.

Wickremesinghe held meetings with the police at another house in front of his residence that was used as his office. The commission concluded that the matters discussed in those meetings were illegal and that the meetings were “inextricably woven” with the maintenance of places of unlawful detention and torture at Batalanda. Wickremesinghe himself, when called to testify before the commission, admitted to convening those meetings and summoning specific police officers, but he could not point to any government decision that authorized him to do so. The report contains a map that shows the houses used by the police and by Wickremesinghe and his bodyguards, as well as the houses thought to have been used for torture.

A rendering of the original map of the Batalanda Housing Scheme produced before the presidential commission of inquiry into torture at the site in the late 1980s. It shows houses used by Ranil Wickemesinghe and his entourage, houses used by the police, and houses used to illegally detain and torture persons.

A rendering of the original map of the Batalanda Housing Scheme was produced before the Presidential Commission of Inquiry into torture at the site in the late 1980s. It shows houses used by Ranil Wickremesinghe and his entourage, houses used by the police, and houses used to illegally detain and torture persons. ITJP

The commission found Wickremasinghe and Nalin Delgoda, the officer-in-charge of the Kelaniya Division, “responsible for the maintenance of places of unlawful detention and torture chambers.” Douglas Pieris, the acting assistant superintendent of police operations, is said to have masterminded and executed the CSU operation. Pieris fled the country on a forged passport in 1996 to avoid scrutiny from the commission. Delgoda said Wickremesinghe held meetings at Batalanda to give “political leadership”, even though he had no jurisdiction over the police under the ministerial portfolios he held at the time.

Pieris, Delgoda, and Merril Guneratne, then a Deputy Inspector General of Police, participated in these meetings, as did officers in charge from other police stations in the Kelaniya area. It was alleged that meetings were held in house number B2, where suspects were being unlawfully detained and tortured. “This circumstance appears to link the holding of these meetings, with the establishment and the maintenance of the places of unlawful detention and torture houses,” the report found. “Further, can a person who took part in these meetings held in this house (B2), ever claim that he was unaware that persons were being detained and tortured in that house.”

Wijayadasa Liyanaarachchi

One victim of Batalanda was the human rights lawyer Wijayadasa Liyanaarachchi, unlawfully arrested by the police for frequently representing JVP suspects in court. He was initially detained in Tangalle, in the Hambantota District on the southern coast, but was transferred into the custody of the Kelaniya CSU. The commission found this highly suspicious and unjustified. According to Ernest Edward Perera, then the Inspector General of Police, it was Wickremesinghe who called him and asked him to hand Liyanaarachchi over to the “Special Team Operating in Kelaniya Division”. Liyanaarachchi was held at Batalanda after his transfer, where he was brutally tortured and eventually killed. A post-mortem revealed that Liyanaarachchi had sustained approximately 207 external injuries and numerous internal injuries all over his body, including two rib fractures and damage to several organs. The commission concluded that this incident indicated the extent of Wickremesinghe’s complicity in the CSU’s activities and that he was in fact handling and directing the operations of the Kelaniya CSU.

Wickremesinghe was a minister under a United National Party government that held power until 1994. Chandrika Kumaratunga and her Sri Lanka Freedom Party took over that year, and in 1995 she appointed the commission of Inquiry to investigate and identify those responsible for the disappearances at Batalanda. The commission’s report was handed over to her in 1998 and only published in 2000, ahead of a parliamentary election that Wickremesinghe was contesting. The report – like reports from other inquiries Kumaratunga instituted – was never acted upon. By then, the civil war with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in the North was again back to high intensity, and the message from the security establishment was that if the government wanted the security forces to fight the war in the North it should not bother them with accountability for past killings in the South. This was yet another betrayal for human rights activists hoping for justice.

In the Al Jazeera interview, Hasan asked about the death of a key witness, Vincent Fernando, who was Wickremesinghe’s “trusted employee”. Fernando had testified to the commission that Wickremesinghe held meetings about the detention of suspects at Batalanda, and that he had overheard Wickremesinghe telling the police to “get them out” – by which Fernando said he understood that the suspects should be “destroyed”. Fernando died mysteriously at the age of 36, a few days before Wickremesinghe was due to testify before the commission.

After we obtained the Batalanda Commission report, several of my colleagues in the ITJP worked on analyzing the document. In 2023, we sent submissions to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture as well as the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions, identifying those with individual responsibility. The lawyer and columnist Kishali Pinto-Jayawardena has pointed out that Sri Lankan commissions used a “peculiarly (legally) imprecise term where criminal accountability is concerned” – namely, that certain people were “indirectly responsible”. Our legal experts were clear that the commission report presented a credible allegation that Wickremesinghe convened and participated in the meetings at Batalanda, which indicated that he in all probability had knowledge of, or had reason to know, the unlawful purposes for which the houses he allocated to the police were being used.

Despite this knowledge, he still proceeded with the allocation, without which gross human rights violations would not have been perpetrated at Batalanda. Consequently, even if Wickremesinghe is deemed not to have had direct responsibility for these violations as a principal perpetrator, he should nevertheless be directly responsible as an accessory to them, either through aiding and abetting or other forms of contribution.

Our legal experts also argued that Wickremesinghe should be held responsible in terms of the theory of command responsibility, as evidence indicates that he had effective control over police activities related to the abuses and had knowledge of such abuses taking place. Given his prominent role in the meetings discussing police activities at the Batalanda Housing Scheme, his physical proximity to the houses where the abuses took place, and his control over the “mini complex”, Wickremesinghe in all probability had knowledge of the abuses that took place there and did nothing to stop, investigate or prevent them.

In a statement responding to the tabling of the report in parliament, Wickremesinghe said he had been “implicated only in the matter of providing housing for police officers, which, as per regulations, should have been done through the Inspector General of Police.” He added, “Nalin Delgoda and I were indirectly responsible for this process.”

Wickremesinghe makes it sound as if he was indirectly responsible for some minor bureaucratic, procedural infringement. What he fails to mention is that these houses were used for torture and illegal detention. What the report concludes is that “Mr. Ranil Wickremasinghe and SSP Nalin Delgoda are indirectly responsible for the maintenance of places of unlawful detention and torture chambers.”

Wickremesinghe, in his statement, also said he was “only summoned as a witness”, not an accused – but everyone who testified before the commission was a witness because it was not a court.

BATALANDA WAS just one of many torture sites in the South of Sri Lanka in the late 1980s. With colleagues from Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka, ITJP has mapped more than 200 sites across the country allegedly used for the torture of Sinhalese, Tamils, and Muslims by the army, police, navy, and paramilitary groups over the last three decades. Sites used for torture include the law-faculty complex of the University of Colombo, the basement of the main building of the state-run Lakehouse newspapers, various schools, colleges, and training institutes, as well as numerous factories, farms, cinemas, and stadiums – and even a golf course.

Aside from the Batalanda Commission, there were also three zonal and one all-island commissions that looked into tens of thousands of disappearances that today seem to have been largely forgotten.

A map of torture sites across Sri Lanka showing produced by the International Truth and Justice Project and Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka. It plots over 200 sites allegedly used for torture by the army, police, navy and paramilitary groups over the last three decades.

A map of torture sites across Sri Lanka is produced by the International Truth and Justice Project and Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka. It plots over 200 sites allegedly used for torture by the army, police, navy, and paramilitary groups over the last three decades/JDS

hose who worked on these commissions were scared for life. They heard extremely harrowing testimony from survivors of mass executions, from witnesses who described seeing heads impaled on stakes and corpses floating in rivers. My Sinhalese colleagues who have dug through old documents have been utterly traumatized by the experience, sometimes stumbling across accounts of what happened to their old school friends. This is the same kind of trauma our Tamil colleagues suffer when they archive statements describing atrocities against their communities during the civil war.

Those few Sinhalese human rights activists who continue to work with the families of the disappeared from the period of the JVP uprising – people like Brito Fernando, who runs a tiny grassroots NGO called Families of the Disappeared – remain deeply committed to those who suffered even as they wonder if they will ever achieve anything for the families of those who were wiped out. Justice seems out of the question; they ask how to get an elderly man his medicine – not the return of his son.

We must advocate for proper reparations for the elderly parents of those killed or disappeared. Some of them – but far from all – received a paltry sum in compensation decades ago, though they lost their families’ main breadwinners. The state’s approach seems to be to drag things on till the victims’ families die. The same thing is happening to Tamil families of the disappeared too.

I started looking into the disappearance commissions from the uprising era to better understand the cycle of impunity in Sri Lanka, which still strangles any attempt to acknowledge the past and move forward. Rather than lump victims from different communities and conflicts together in their suffering, it made sense to look at the continuity of perpetrators. The same police and army officers – and also politicians – who were implicated in the appalling crimes of the late 1980s in the South often went on to hold positions of command during the civil war. They were never held accountable for violations against Sinhalese and then repeated them against Tamils. One case in point is Shavendra Silva. Another is Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the former secretary of defense and later president. There are many others, including Janaka Perera, who was involved in crushing the JVP uprising and went to be an army commander in Jaffna at a time when over 700 people disappeared.

The disappearance commissions in the South came up with lists of hundreds of officials against whom to file criminal charges. There were even some cases filed by magistrates and high courts in the South. The relevant court documents appear to have disappeared in the intervening years, but several so-called “heroes” of the civil war were accused of multiple disappearances of Sinhalese civilians in the South when they were young officers.

The eyewitness testimonies and the lists of “names of suspects that transpired” in the course of the commissions’ work were put under seal in the National Archives by Kumaratunga’s government until 2030. It is high time that this classified information was released to the public – that is if it had not already been destroyed. (Before public release, all such information from this era should be handed to the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka to redact the identifying details of men and women who were sexually violated.) It is a vital part of the history of the country that the younger generation in the South and beyond needs to know. Then young Sinhalese can understand that the violations that Tamils describe – white-van abductions, illegal detention, torture, sexual violence – all have their roots in the JVP era and were practiced on Sinhalese civilians.

In the meantime, I suggest reading old reports from Amnesty International – an organization that Wickremesinghe mendaciously told Al Jazeera has been discredited in Southasia. These detail white-van abductions in 1989 in the South (“The same evening two men were seen by witnesses being detained by men, who were presumed to be police and who used a white Hiace van, near the Katunayaka playground”); the branding of detainees (“I saw a red-hot iron, one soldering iron and one iron rod”); and sexual violence, including against men (“Men and women prisoners have reportedly been raped, and male prisoners have said that they were forced to sexually abuse women prisoners”). The gruesome torture methods described in these reports, used by the security forces against Sinhalese, are very familiar to anyone working with Tamil victims of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict.

It is no coincidence that the attacks I have faced, accusing me of being a terrorist and a meddling foreigner, have come from those close to the security establishment. It is they who have the most to fear from the truth about the state’s violence during the uprising coming out.

There has been a lot of talk about truth and reconciliation between Sinhalese and Tamils in Sri Lanka, but very little of this has been achieved. Perhaps acknowledging the truth about the crimes committed at Batalanda is a starting point for a new generation to deal with the past.

Many in Sri Lanka increasingly view the government’s reopening of the Batalanda issue as just a cynical exercise to weaken a political opponent. They point to the JVP’s violent past and the difficulty the party has in acknowledging it. But there is an inherent unpredictability in taking the lid off a period of history that has been so suppressed and yet is still in living memory.

Wickremesinghe’s outright denial in the Al Jazeera interview backfired badly. The current government needs to learn from that.

Sri Lanka’s ex-president in the hot seat over torture site