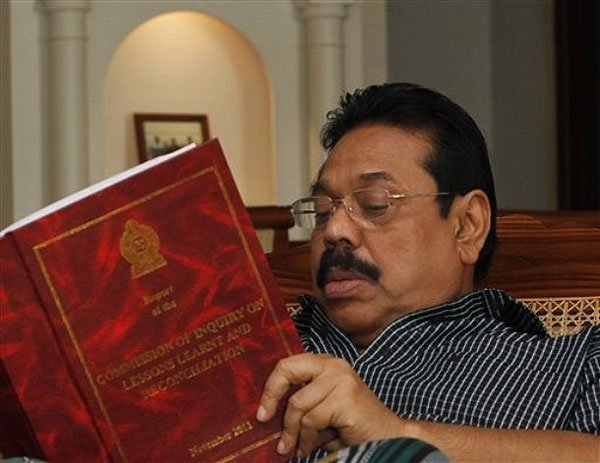

President Mahinda Rajapaksha appointed the Lessons learnt and Reconciliation commission in May 2010 and after 18 months of sittings, the commission submitted its report to the President in November 2011. The report is not only about the effects of war but also about the need to depoliticize state institutions and foster good governance. However, at the time of writing, the report is not yet accessible in Sinhala or Tamil, even though it was reported in the media that Sri Lanka’s Central Bank had commissioned the translations. As Kishali Jayawardena argued, many commissions of inquiry in Sri Lanka have been political exercises rather than genuine attempts to reconcile a traumatized nation.[i]

While there are many national level civil society discussions on the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC), there seems to be very little discussion on what citizens say about the LLRC and its recommendations. However, there is widespread hope that public demands will create the space to implement the LLRC recommendations and find ways towards reconciliation among different ethnic communities. With this objective the International Centre for Ethnic Studies (ICES) in collaboration with the National Collaboration Development Foundation (NCDF), a community based organization, organized workshops in Kanthale in Trincomalee. In Trincomalee district there are Sinhalese, Tamils and Muslims in similar proportions in the population.

The workshops focused on raising awareness about the LLRC and its recommendations. We conducted four workshops from April to July 2012 with farmers, youth, civil society groups and representatives from political parties. There were 140 participants and members from all three ethnic communities took part in these workshops. This article will discuss workshop participant’s views on the LLRC.

The views expressed at the workshops on the LLRC are not different from the views of the government’s positions on the LLRC. However, the participants were not aware of the content of the LLRC. Once we presented its recommendations

,they started to talk about their issues and problems with regard to them. The majority of people who participated in the workshops were Sinhalese. Discussing the causes of the war, the participants related those to the LLRC. They think that the international community and politicians should take the responsibility for the problems and issues facing Sri Lanka. A senior citizen, aged over 65 said that,

“The LLRC is an international conspiracy”(meva jathyanthara kumanthrana). Even in the past these imperialists tried to suppress us by using many mechanisms. From Elara’s time to the current situation it is evident”.

Some of the Sinhalese participant’s views on the initiation of LLRC are not different from the views of Tamil participants of the workshops. Tamil participants also thought that the international community pushed the LLRC forward. But the difference is that though Tamil participants thought that it came out of international pressure, they think it is a positive attempt by the international community.

In the current political context, the LLRC is often portrayed as a tool for international interference alongside the UNHCR resolution of March 2012. In relating the LLRC to the UNHCR resolution most of the Sinhalese participants expressed the view that the international community wants to divide the country. We only have this country; they don’t want us to be together. The government’s main narrative in relation to the Geneva resolution was that ‘justice’ was defeated by power[ii]. If the government sees the LLRC as a home-grown process, then how does the international community, seeking to enforce the LLRC recommendations, undermine ‘justice’?

Since the publication of the LLRC report, the government has shown signs of backtracking on these recommendations. According to the participants, during the debates on the UNHCR resolution, some people related to the Defence Ministry and other nationalist intellectuals had gone to the Kanthale and spoken to people about the effects of the “international conspiracy”. The LLRC report explicitly recognizes that the primary responsibility in relation to reconciliation in Sri Lanka is with the government. However, these duplicitous efforts by the government show that it is unwilling to create the space for reconciliation.

These participants didn’t know that the President appointed the LLRC. Furthermore, they didn’t know anything about its recommendations but they thought that it existed to divide the country. As for the second reason the country is facing problems, Sinhalese participants claimed:

“Our politicians support the creation of this kind of intervention. Mr. Bandaranayake did engage with regional politics. When he goes to Jaffna he said we will give you equal opportunities (sama thana denava) at the same time he said the same thing to the Muslims. However, when he goes to the South he says that the Sinhalese are the majority. No one can ask for anything the Sinhalese don’t like. This is the person that made Sinhala the only official language”.

In general, Tamil people have heard about the LLRC. But they also don’t know what it is, or who created it, nor its implications. Most of the participants of the Tamil medium workshops were women, and they said that whatever the commission was, their grievances should be addressed by it. They said, even though they are happy with the end of the war, there are many issues in their community regarding language, education, gender violence and illegal drugs. They discussed all their problems in the workshops.

“The main problem for us is that every day the police and the army come to our houses and check for former LLTE cadres. They take many former LTTE carders away for questioning. Now what has happened is that our youth have started to leave the country”

They discussed how their social environment has begun to change since the end of the war. A female participant said:

“There are many reports of child abuse and rape cases. Every day we can hear something about child abuse. There are many widows as a result of the war. They are facing difficulties when they travel by bus. If they are nicely dressed, most of the time they face difficulties. Many women have started to wear different clothes that were not familiar to us before the war. The cultural dress codes have started to change.”

The LLRC discussed the issue of the overt military presence in the north and its implications on the local population. They have highlighted some of the representations made before it such as the need for defence ministry clearance even to have civil functions such as weddings. The views of the Sinhala people who participated in the workshops differ from this. “There are many police and army personnel here. But we don’t have a problem with them. We don’t have any issue with them keeping guns if they are not targeting us”. When we discussed this issue in the first workshops, participants did not believe that there are negative aspects to militarization.

The LLRC has shown the need to take steps towards the development of the Northern and Eastern Provinces. Many of the representations made before the commission relate to the nature and substance of development required in those areas. Particular problem areas include fisheries and agriculture. The most significant means of livelihood for the people in the Kanthale area is agriculture. Therefore, most of the inter-community problems have been shaped around the matter of sharing water. Sinhalese have problems with the Muslim community regarding water supplies for their agricultural activities. To resolve these problems with the other communities, the participants emphasized the need to have a policy about the lake and water supply.

Most of the people in Kanthale accept that there are problems for the Tamil people in relation to language. Tamils and Sinhalese both recognized that language is as a cause of their grievances. A Sinhalese participant said that,

“Before 1956 our names on the birth certificate were in Tamil. For example, if my name is Punchi Banda, it was written on the birth certificate as Punchi Vanda. Mr. Bandaranayake changed it. But now Tamil people have the same problem, everything is in Sinhala. They come and ask us for help. A Tamil person said, “We have many issues in relation to language. There are many public meetings but we don’t know what the officials say. We can’t communicate with the police. If there are fixed prices for everything at the market it is good, because we can’t bargain due to the language issue. Our children lost many opportunities because of the language issue. We think the ‘56 Sinhala Only Act should get the blame for all these problems.”

Workshop discussions showed how majoritarian politics have played a role in not solving problems but creating them. The LLRC recognizes the importance of language policy and practice in reconciliation processes. The Commission has emphasised the need to implement structural and administrative adjustments in relation to language policy, such as ensuring all government offices, including police stations, have bilingual officers who are accessible at all times. The LLRC also emphasized the symbolic relevance the National Anthem being sung in both languages; Sinhala and Tamil.

With the acceptance that there are problems specific to Tamil communities, many participants have suggested power-sharing at an administrative level, rather than a regional level. There was a senior citizen who said, “They have problems in relation to their day-to-day lives, especially language problems. Therefore, we have to devolve power but keeping the “thone lanuva” (rein) in the central government’s hands. If they try to ask for a separate state then we can stop them using that power”. The stated Tamil specific problems are not considered. Living among different ethnic groups, Tamils and Muslims are familiar with each other’s grievances. Therefore, both communities accept that there are ethno-specific problems that require solutions. There has been a tendency among the Sinhalese to oversimplify Tamil grievances and reduce them to the language issue. Dialogue to understand and accept other grievances should be considered.

There are also problems between Sinhalese and Muslim communities. A villager said: “We are the oldest people in this village and as Sinhalese we are a minority in Trincomalee District. We have problems with Muslims in Kinniya regarding water supply. Whatever problems arise, the government first tries to solve their problems. What we say is – the government has to provide assistance equitably”.

Mentioning issues in regards to their lands, many of the participants said that to, “integrate two communities by settling Sinhalese in Tamil areas will also be the solution for the problems they face in their everyday lives. Then they won’t ask for separate lands for their people”. The solutions they suggested can be seen as synonymous with government sentiments and policies. Even though the idea of a mixed settlement is seen as a solution for the problems, it has been developed by the Sinhalese, not by the Tamils.

This commission was supposed to achieve truth and reconciliation, however, evidence shows that it hasn’t achieved this among the people. J.C. Weliamuna has argued that unless there is sufficient and intensive demand by the people of this country on the streets, the government will not even consider implementing these recommendations.[iii] In my view, to get popular support on this issue, civil society organisations will have to make further efforts to remedy the grassroots level opinions and misunderstandings of the role and function of the LLRC.