Changes since the end of the war:

30 months after the end of war, more people travel between the once off limits North[i] and the South and many of the travel restrictions have been eased. The dreaded Medawachiya checkpoint is no more, and since 2010, we have not taken a flight or ship to Jaffna, travelling by road instead.

Displaced people who were detained for about 6 months have now been allowed freedom of movement and many have been allowed to go back to their places of origin. Many youth detained in “rehabilitation” centres have been released and allowed to go back to their families and communities. Death certificates have been issued to few of the people killed during the war. Few schools, hospitals, and some main roads and bridges have been built and glamorous ceremonies held to open these by government and military officials. Three major elections have also been held in the North.

But much remains to be done for Northern Tamils to be able to live in dignity and for the country to move towards reconciliation.

In the last few months, we had spent a considerable amount of time traversing the major towns and roads as well as remote and interior villages and roads in Northern Sri Lanka. We had managed to reach some interior villages after questioning by suspicious and curious soldiers. We had survived without running water, electricity, beds, long nights battling mosquitoes, long bumpy rides in dusty buses on roads that felt more like tracks in a wild life parks and numerous other challenges. But the difficulties we encountered pale in comparison to the difficulties people we encountered were facing and often we felt helpless and powerless to help them.

Below are some of concerns regarding the situation in the North and prospects for reconciliation, based on what we saw and heard first hand, complimented by some additional desk research for information and statistics we couldn’t find on the ground and additional references that re-confirm our findings.

1. Fate of those killed, disappeared & injured and their families:

In almost every village in the North we have visited, especially in the Vanni, we met families of those killed or disappeared during the last five months of war in 2009, in the years 2006-2009 and decades of war. In a submission to the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission on 8th January 2011, the Catholic Diocese of Mannar, led by the Catholic Bishop of Mannar, Rt. Rev. Dr. Rayappu Joseph, asked for clarification about the fate of 146,729 people who were unaccounted for between October 2008 and May 2009, based on government statistics and documentary evidence.[ii] The submission also included a list of 100 people disappeared from the Mannar district between 2007-2009 and list of 166 persons reported as killed from the Mannar district in the last phase of the war. There has been no response received from the LLRC or any government official to these.

In almost every village we had visited in the Vanni, the former LTTE controlled areas, we also met people injured in the war. We have met people who lost both legs and those who have lost legs and arms and variety of other injuries and related sicknesses. Most of them have not received adequate assistance and struggle to live productively, with some finding it difficult to even continue medical treatment.

2. Detention and release of alleged LTTE suspects:

We also met many families whose loved ones have been detained for long time. According to the government, 876 persons are held in administrative detention at the Boosa detebtion facility in Southern Sri Lanka and 863 of them are Tamil.[iii] No information is provided about the period of their detention and we had heard about cases where detainees have been in detention for more than ten years without being convicted. In addition to the around 280,000 displaced who were detained, the number of those detained in “rehabilitation” centres is believed to be 12,000. There is no fixed and exact official figure, with various government officials and politicians giving different numbers at

different times. The government claimed 1000 were in “rehabilitation” centres as of 17th Oct. 2011 out of 11,951 that were on “rehabilitation” – voluntarily & based on court orders, plus a further 994 that had been transferred from custody of the Terrorist Investigation Department to “rehabilitation” centres. [iv]

In an interview to the Sunday Observer of 9th October 2011, reproduced in the official website of the Bureau of the Commissioner General of Rehabilitation, the Commissioner General of Rehabilitation had claimed that “Those who were fully involved with the LTTE were removed to Boossa and there was a fair amount of such people” and that “The TID categorized the people and took away those in the categories A,B & C; LTTE leaders, strict followers, and those who were assigned to recover things and arrest others”.[v] There is no information provided about how many were taken away, their names and details and where they are now.

Given history of enforced disappearances, torture and long detention in Sri Lanka this lack of uncertainty in numbers, together with lack of centralized list of detainees indicating place of detention and transfers, raised serious concerns about security of those in detention.

There is no clarity regarding whether or not or when the 1000 remaining in “rehabilitation” would be released or prosecuted. Different government officials and politicians have given different numbers that would be prosecuted, with no one indicating a time frame.[vi] Despite the lack of clear official statistics about how many entered the “rehabilitation” process, the Commissioner General of Rehabilitation implies that most of the 12,000 surrendered in May 2009 after the death of the LTTE leader.[vii] In the same interview, the Commissioner General admits that the maximum period these persons could be kept lawfully in “rehabilitation” is two years – raising concern that the 1000 remaining as of 17th October 2011, and indeed the majority of those kept after May 2011, are / were being kept illegally.

One of the alarming developments seen since the end of the war has been the threats, intimidation and restrictions placed on detainees released. Those released are being subjected to repeated registration, surveillance, interrogation in their homes and military and police camps. Many had restrictions placed on freedom of movement, such as getting permission of military before they leave their villages. [viii] At least one such person we met had been re-arrested, detained in Kandy for about a month in which process relatives observed signs that he was tortured.

3. Detention, release, “resettlement” and imminent forcible relocation of the displaced:

The mass detention of more than 280,000 Tamils from the North who had borne the brunt of the last phase of the war was amongst the most visible outcomes of the end of the war throughout most of 2009. Probably due to massive international and some local pressure, Tamils detained began to be gradually released, starting with children, elderly, injured etc. and by end of 2009, most people detained were granted freedom of movement.

From end of 2009, those displaced who were released were gradually allowed to go back to their villages in the formerly LTTE controlled areas. However, people are not allowed to go back to resettle in at least 9 villages in the Mullativu district and several more in Mannar, Killinochi and Jaffna districts which are presently occupied by the Navy and Army.

According to the latest Joint Humanitarian Update on the UN OCHA website, based on statistics of the GOSL[ix], as of end of September 2011, more than 120,000 people remain displaced.

65,008 persons who were displaced in the last phase of the war in the North after 2008 remains displaced, with 7,534 in camps and 57,474 being with host families. The update also notes that a further 55,616 remains displaced, having being displaced prior to April 2008. This number includes 8,013 in camps and 47,603 with host families, and is likely to include people from both the North and the East.

One of the new concerns is the Government’s decision announced on 20th September 2011 that 7,394 persons still living in Menik Farm (at time of announcement) will not be allowed to go back to their villages, but will be settled elsewhere, in Kombavil, a jungle area in the Mullativu district..[x] While we were not able to obtain official information as to what these villages are, information provided by displaced people indicate that the military is occupying 9 villages, not allowing displaced civilians to go back. From what we learnt, these villages includes Puthukudiruppu East, Puthukudiruppu West, Sivanagar, Manthuvil, Malligaitivu, Ananthapuram in the Puthukudiruppu DS Division and Mulliwaikal West, Ampalawanpokkani & Keppappilavu in the Maritimepattu DS Division. Despite go and see visits to Kombavil, many residents had expressed their unwillingness to go to Kombavil, and some had submitted a petition to the National Human Rights Commission in this regard.

We visited Kombavil twice in the last two months and observed that government appears to be going ahead with plans of compelling people in Menik Farm to resettle in Kombavil, despite people’s concerns. The latest Joint Humanitarian Update confirms that there is no confirmation that these people would be allowed to go back to their own villages or a timeline for such an eventuality, and also confirms that issues such as access to seaside fishing areas, farming/paddy land, access to adequate health services and alternative choices other than Kombavil are yet to be resolved. [xi]

The slow return of some Muslims forcibly evicted from the North by the LTTE and Sinhalese who had left the Northern Province, has also started, and this is indeed a positive development. Some such returns have led to tension between communities, primarily based on land issues and allegations of resource allocations. Preventing such tensions and ensuring that all communities have right to return to an conductive atmosphere where they can rebuild shattered lives, in a way that does not affect the rights and sensitivities of other communities has emerged as major challenge. For example, Tamils around Madhu road in Mannar district claims that there were 22 Sinhalese families in the area in 1990 and that 180 have requested for housing to the Assistant Government Agent of Madhu Division. TNA Member of Parliament, M. A. Sumanthiran has pointed out that that 45 houses have been provided by a state Bank while only 5 have been provided to Tamils in the area. [xii]

4. Militarization:

In the last month, several well known peace activists, senior lawyers and journalists have pointed out that two and half years after war, the whole of Sri Lanka and many facets of life, remains heavily militarized.[xiii]

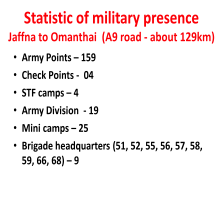

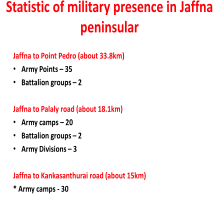

In our visits to the North, it was clear that the North remains heavily militarized and this continues to be resented by the Tamils in the North, many of whom believe the military is responsible for killing, disappearing, torturing, and sexually abusing Tamils during decades of war. Tamils also see the military presence as an obstacle to restoration of normalcy and civilian life in the North in the post war era. The military continues to be the most visibly present and dominant institution in the North, particularly in the formerly LTTE controlled areas. According to the official website of the Ministry of Defense, a “new Security Forces Headquarters Complex at Kilinochchi, comprised of an air-conditioned conference hall plus a separate auditorium, administrative offices, computer and signal room, mess hall and a few other wings was ceremonially opened” on 21st October and this had cost Rs. 40.6 million (around USD 369,000)[xiv]. According to TNA MP Sumanthiran, “there is one member of the armed forces for approximately every ten civilians in the Jaffna Peninsula”[xv]. According to military’s own statistics, in Jaffna, there are more than 35,000 troops[xvi] for an estimated 626,329 people[xvii], an average of one military personnel for every 18 civilians, which includes children and senior citizens. Defense Ministry quotes the Secretary of Defense saying that “Military Intelligence Corps had to be increased to 6 battalions from the original 1-2 battalions”[xviii]. Militarization is a dominant part of parcel of live in the North (and East as well), over riding and sidelining elected representatives from the area and civilian administrators. The Governors of both the North and Eastern province are senior military officers and Government Agent of one of the districts (Trincomalee) is also a former military officer. The military plays a dominant rule in controlling civil and religious bodies and community and social life. It has also encroached into law enforcement, resettlement, rehabilitation, development, sports, cultural, shops, restaurants, hair salons, farms, transport and even touristic activities. Examples of some of these are provided below. In all the village level Development Committees in Jaffna, the President is a military officer. [xix] Some village development committees, such as Pachchilaipalli 2, comprise entirely of military officers.[xx]The civil military coordination website claims that it’s Misison includes even the upliftment of people through “spiritual values”[xxi].

5. Degrading and discriminatory registration of civilians in the North:

Civilians in the North have been subjected to repeated registrations by the military during the war and also after the end of the war. But even in 2011, this continues to happen in the Vanni and also Jaffna.

Despite the Attorney General agreeing to suspect registration of civilians in Jaffna & Killinochi districts by the military in February 2011 after a five TNA Parliamentarians of the Jaffna district filed a fundamental rights application, registration continued. Various other forms had also been distributed in Jaffna by the Police for purpose of registering civilians.

6. Occupation of land:

Large amounts of private land, and sometimes whole villages have been occupied by the military and there have been no compensation schemes announced for these long takeover of land. Many such properties continue to be occupied by the military. The military also occupies state land, and bypasses administrative laws and procedures in putting up structures at their own whim and fancy, such as shops, restaurants, farms, monuments etc. One of the most blatant incidents is the occupation of Mullikulam village in the district of Mannar since September 2007 by the Navy, without following any legal procedures and displacing the entire population indefinitely. According to the Civil-Military website for Jaffna, 200 hectares of land is inaccessible for cultivation due to High Security Zones and further 6000 hectares of land is not in use due to effects of conflict[xxii]. According to TNA MP Sumanthiran, “Tamil people inhabited 18,880 sq km of land in the North and East, but after May 2009, the defense forces have occupied more than 7,000 sq km of land owned by Tamil people”[xxiii].

7. Continuing violence in highly militarized North:

Numerically, numbers of those reported as killed, disappeared, arrested and tortured have gone down in 2010-2011 compared to 2006-2009. But people continue to live in fear in the North as killings, disappearances, sexual abuse, robberies, extortion continue to be reported from the North since the end of the war. In a three month period of November 2010 – January 2011, 40 such incidents were reported, predominantly from Jaffna.

In August 2011, the military and police conducted a spree of attacks on civilians and threatened religious leaders in Jaffna, Vavuniya and Mannar, in relation to protests and concerns of the civilian population regarding military complicity in relation to attacks on women by “Grease devils”.[xxiv]

Like before, these incidents seem to happen despite a large and dominant presence of the military on a scale not seen in the rest of the country, bringing about well founded suspicions of the military’s tacit or explicit involvement in these incidents.

One of the most shocking and brutal violence by Police against Tamil civilians was seen on 20th September 2011, when Mr. Udaya Pushparaja Antony Nithyaraja (31) of Jaffna District was severely tortured by police officers in the premises of the Jaffna Magistrate Courts[xxv].

8. Violence against women:

Many women complain of rape, sexual abuse, including by military officials[xxvi]. Women complain of soldiers visiting houses when there are no men, telephone calls and sms (text) messages etc. There have also been allegations of trafficking. Several soldiers were arrested for rape of women in 2010 in Vishvamdu. Women also have been the prime target of attacks by “Grease devils”[xxvii]

9. Attacks on dissent and threats and restrictions on freedom of expression, assembly and association:

On 16th October 2011, a Jaffna University Student Union leader, who was also a well known as an outspoken civil rights activist, was brutally assaulted [xxviii] while on 29th July 2011, senior journalist and news editor of Uthayan was severely assaulted.[xxix] Both these attacks resulted in victims being rushed to Jaffna hospital for treatment. On 28th May 2011 one of Uthayan reporters was attacked by armed thugs when he was on his way to work.[xxx] The individuals and organizations have been known critics of the government. On 24th July 2011, Networking for Rights, an exiled group of Sri Lankan activists and journalists reported that two foreign journalists had been interrogated at midnight in Jaffna by Police and were compelled to leave the region and that the next day, they were attacked and robbed at gun point.[xxxi]

Several human rights defenders in the North have been subjected to threats and intimidations since the end the war. On one occasion, the names of a group of human rights defenders that participated in a human rights training in the North were printed in a mainstream national Sinhalese newspaper, along with the organizers, portraying all as traitors.

Several others have been questioned by military and intelligence and beaten. One was stopped and questioned at the airport in December 2010 and another questioned and slapped on arrival at the airport in September 2011.

On 16th June 2011, a meeting of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), the political party which won comprehensively in successive elections in the North, was broken up by the army and peopling attending the meeting attacked.[xxxii] In June 2011, it was reported in the Sinhalese newspaper “Ravaya” that the military had threatened people in Vanni not to participate in a protest of families of disappeared people and subsequently detained and interrogated two of the organizers. On the night of 1st April, a Catholic Priest who had spoken out about problems facing civilians in Jaffna at a meeting with the visiting Congress of Religions delegation, had cow dung thrown at him.

Such incidents have also instilled fear amongst human rights defenders, journalists, opposition politicians and anyone holding dissenting views with the government.

Many NGOs and church groups keen to engage in counseling, community organizing and provision of other materials and services to people in the North continue to complain about restrictions and stringent regulations imposed by the Presidential Task Force (PTF). The difficulties in obtaining permission to provide any form of assistance drives away and discourages many groups and individuals keen to help people affected by the war, and this denies desperate people from receiving much needed support.

In many areas of the North, particularly in formerly LTTE controlled areas, the military demand advance notification of any social events and attend such events without invitation. On one occasion, Police officers interrupted the awards ceremony of a cricket tournament and took away a trophy on offer, alleging that it was in the name of a former LTTEer. In actual fact, the trophy in question was donated by family members in memory of parents that were dead.

10. Restrictions on freedom of movement in the North:

Despite the opening up of the A9 road in December 2009 and easing of some travel restrictions between the North and the South, travel restrictions still remain to the North. The Omanthai checkpoint serves as a separation of the North from rest of the country, and the separate and concept of entry / exit is indicated by a board that says “remain here until you are granted entry”.

In July 2011, a Sri Lankan journalist faced restrictions on travelling in the North, including being detained and questioned at an Army camp for several hours. Also in July 2011, days after an official announcement by the government that restrictions on travel for foreign nationals to the North have been lifted, the Ministry of External Affairs has insisted on additional documentation such as pre-planned travel itinerary for a visiting foreign national, who had a legitimate visa to visit Sri Lanka. The military officials allowed her to pass the Omanthai checkpoint, the main entry point to previously LTTE controlled areas, only after she showed a letter authorizing her to travel to specified cities for a specified time period from the Ministry of External Affairs, which according to her had been issued after obtaining approval of the Ministry of Defense. A friend from north who had called the Ministry of Defense was told that foreign nationals can only travel on the A9 road, and travelling to interior villages still required prior permission.

11. Sinhalese – Buddhist domination:

Fears and unhappiness about Sinhalese – Buddhist domination in predominantly Tamil areas was repeatedly expressed by people we met. We ourselves saw many indicators of such attempts. TNA MP Sumanthiran’s report to Parliament raises concerns that “steps are being taken to divide the District of

Mullaitivu and create within it the new District Secretariat division of ‘Weli Oya’ and that there are orders issued to “to have Tamil civil servants removed or transferred from the North and to fill the vacant posts with Sinhala trainee civil servants and that one hundred and forty Sinhala civil servants have been relocated to the North as part of this initiative and Tamil civil servants have been ordered to go on compulsory leave, and further, that these drastic measures must be viewed in the backdrop of systematic deliberate exclusion of Tamils in the civil service in selection processes, promotions, trainings and development opportunities”[xxxiii].

Despite the North being predominantly Tamil, many road signs continue to be in Sinhalese. We noticed several such Sinhalese names around Mullativu on the eastern coast of Vanni and around Mulangavil and Adampan on the western coast of Vanni. We also observed several road names in Sinhalese only, named after Sinhalese soldiers.

Even some release letters for detainees, forms collecting socio-economic information are not in the Tamil language in the North.

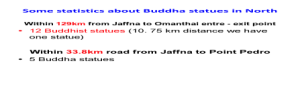

The North also remains predominantly Hindu and Christian, and thus, the building of several new Buddhist statues and structures have also made Northern Tamils fearful of Buddhist domination of the North.

12. Lack of shelter, livelihoods, healthcare, educational, transport facilities:

30 months after the end of the war, people whose houses were razed to the ground due to no fault of their own, have not been provided houses by the GOSL. The few houses that have been provided have been built through people’s own efforts and with support of their relatives, friends, foreign governments, and private groups. However, all over the Vanni, military has been provided with housing that appears of much better quality than the housing displaced persons are compelled to live.

Some schools damaged in the war are still not repaired and it is common to see classes conducted in open air. Some schools are still occupied by military and some are still closed. TNA MP Sumanthiran sites examples of schools occupied by the military as Keppapilavu GTM school in Keppapilavu, Mulliyawalai, Mullaitivu, the Maththalan R.C.G.T.M. School in Mulliwaikkal, Mullaitivu, Mullivaikkal West K.S.V Mullivaikkal,Mullaitivu Mulliwaikkal East GTM School, Mulliwaikkal Mullaitivu, Vikneshwara Vidiyalayam Pooneryn, Arasaratnam Vidyalayam Manthuvil Puthukkudiyiruppu, Sivanagar Tamil Vidyalayam Puthukkudiyiruppu Mullaitivu and the Myliddy, R.C.T.M.S Mylidy, Kankesenthurai[xxxiv].

Hospital and medical facilities also remain scarce and often, people have to walk long distances and queue up for healthcare. According to the latest Joint Humanitarian Report, many primary medical care units and divisional hospitals in the North are still not functioning. [xxxv] TNA MP Sumanthiran’s October report to Parliament highlights inadequate health services in the Vanni, citing the This avoidable death of patient deaths, such as the death of a girl on 7th October 2011 as a result of untreated rabies[xxxvi].

Livelihood options remain scarce and most people live improvised and poor lives. Although some have been provided livelihood support by UN, church groups and NGOs, many remain improvised. A major o obstacle to develop livelihoods based on local resources has been the military encroachment into livelihood activities. The military regulates fishing, issuing passes to go to sea. Fishermen in Mannar district showed us three separate forms that require 30 signatures plus photos and additional documents, to enable fishermen to go fishing.

Some Northern Tamil fisherman allege that military often gives special privileges to Sinhalese fisherfolk from the South. The report tabled TNA MP Sumanthiran notes that while there are restrictions on fishing by Tamil fishermen in villages in Mullativu district such as in Kokkilaai to Chundikkulam in Kilaakaththai, Maathirikkiraama, Uppumaaveli, Thoondai, Alambil, Semmalai, Naayaaru, Kokkuththoduvaai, and Karunaattukkernee, Sinhala fishermen in the area have received direct permission to fish in this area from the Ministry of Defense. He also claims that while Sinhalese fishermen are given preferential treatment to fish in the North, Tamil fishermen are not given reciprocal permission to engage in fishing in the South[xxxvii]. Mr. Sumanthiran also reported that “people returned by the government to Uduththurai in Maruthenkerny (Vadamarachchi East), were soon after evicted from their houses along the coast and placed in transit camps on the other side of the coastal road. These houses are now being occupied by people brought from the South who are permitted by the Ministry of Defense to engage in diving for coral and star fish”[xxxviii].

In our visits to the North, we saw that the military has also started a large number of business, such as restaurants, shops, farm, hair salons, holiday resorts and tourism projects, denying the local people the opportunity to develop their own initiatives using local resources. The Civil-Military Coordination website lists “Tour Guide Service” amongst the services it offers[xxxix]. It appears that the military is using state resources for some of these activities and the legality of some of these activities is in doubt.

TNA MP Sumanthiran also highlighted the situation of unemployment in the North and East, saying “ The limited opportunities available are consistently given to individuals of the labour workforce from the South. Estimates suggest that unemployment in the Northern Province is between 20% to 30% in the Northern Province, compared to a National average of 4.3%. The reservoir bunds repair and road construction of the A9 road and the secondary road have been handed over to Sinhalese contractors from the South who bring in their own labour force. Only an insignificant number of Tamil labourers are employed by them despite the fact that there are numerous Tamil youth and men who are unemployed in the Vanni”[xl].

13. Impunity, allegations of war crimes, calls for international inquiry and LLRC:

Many human rights violations, abuses, criminal and illegal activities since the end of the war, including some mentioned above, continue unchecked and it appears that rule of law simply doesn’t exist in the North or a different sets of rules and laws apply in the North, distinct from rest of the country.

Allegations that grave violations of international humanitarian and human rights law occurred during the last stages of the war, particularly from January – May 2009 is a recurring theme in the post war scenario. Allegations have been leveled against both the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE. However, with killing of the LTTE chief along with other top leaders, the focus of accountability has focused on the Sri Lankan government, given also it’s national and international obligations as a state. Allegations included the killing of thousands of civilians due to shelling and bombing, targeted shooting, attacks on hospitals, schools, churches, restrictions on essential humanitarian assistance including food and medicine. Civilians, doctors, religious leaders and militants who survived the last months of the war had given a number of first hand eyewitness accounts to the government appointed Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) when it held sessions in the North. University Teachers for Human Rights – Jaffna, a Sri Lankan group with a reputation for detailed reporting of human rights violations during the decades of war, produced a damning report of abuses by both the Government and the LTTE, while international human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch and the International Crisis Group also produced detailed reports containing such allegations. The United States of America Department of State also produced a report containing similar allegations. The last and most damning report came from a panel of experts on accountability in Sri Lanka, appointed by the UN Secretary General. Video and photos have also been circulating projecting horrific civilian casualties, including the shooting of unarmed LTTE cadres who had surrendered. A June 2011 50 minute documentary film produced by Channel 4, a British TV channel, and certification of the authenticity of some video clips by UN experts have raised visibility of allegations of war crimes nationally and internationally.

These allegations have led to calls for an independent international inquiry, by several western governments, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, international human rights groups and large numbers of Tamil Diaspora. Even the Indian government, which in the past had shielded the Sri Lankan government from criticisms, recently took a position that concerns being raised with regard to the sequence of events in the last days of the war needs to be examined. The failure of the Sri Lankan criminal justice system and a number of adhoc Presidential Commissions of Inquiry to establish the truth and ensure accountability for large and serious rights violations related to the war as well as unrelated to the war, such as extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, torture, sexual abuse have given credibility for calls for an international inquiry.

The government’s response has been on one hand, a blanket denial that any violations of international human rights and humanitarian law took place in the last days of the war. On the other hand, the government has gone to great lengths to try and convince domestic critiques and the international community that Sri Lanka’s domestic processes, particularly the recently appointed LLRC is capable of dealing with any allegations of human rights and humanitarian law during the war. Questions about independence of the LLRC, whose Chairman and several members have served the incumbent regime and even defended allegations against the regime in international forums have not instilled confidence and hope of those calling for international inquiry. Witnesses had received death threats, one told us that he had been questioned three times by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) between January 2011 (when he gave the testimony) and October 2011 and others have been visited by intelligence officers. The lack of victim and witness protection program, restricted mandate including the scope to look at only the specific period of 2002-2009, and lack of respect paid to victims and families who came forward to testify before the LLRC have further indicated the inability of the LLRC to serve as a credible accountability or transitional justice mechanism. One the damning indictments against the LLRC process is that after more than one year, key interim recommendations by the LLRC has not been implemented by the government, including releasing a list of detainees.

Until and unless there is a credible domestic mechanisms that is seen as independent, particularly by victims, survivors, their families and others who have leveled allegations, calls for international inquiry is likely to continue.

14. Ethnic and north – south polarization; celebrations in the South and mourning in the North:

Despite the fact that LTTE prevented civilians from leaving the war zone, including by shooting at people who tried to escape, the government’s claim that it had undertaken a “humanitarian operation” and “liberated / rescued civilians held hostage by the LTTE” didn’t appear to have any acceptance amongst the Tamils in the North while in other parts of the country, this claim appeared to have gained varying degrees of acceptance.

The visible response in areas outside the North and East of Sri Lanka when the war ended was one of joy and celebrations. This was predominantly the response of the majority Sinhalese community, in line with the position of the government of Sri Lanka. If those who had survived in hand dug bunkers felt some relief when finally the shelling, bombing and shooting stopped, it was not visible. What was visible in the North was tears and mourning for large numbers of Tamils killed, disappeared, injured and displaced.

This polarization was again visible during the 1st anniversary of the end of the war. The south celebrated with a grand victory parade, while in the North, the military cancelled the solemn and subdued low key religious – cultural events organized to grieve and mourn for those killed and disappeared. Those who organized and attended these events, including several Catholic priests, were threatened by the military. A Catholic priest who attempted to build some small monuments for those killed in the war was also threatened by the military. Cemeteries and memorials of Tamil militants in the North, where family members used to go to say a prayer, lay a flower and light a candle, were raised to the ground. Even the house of the LTTE leader’s parent’s in Jaffna was vandalized and when his mother passed away, her remains were desecrated. On the other hand, massive and posh looking monuments for Sinhalese soldiers had come up in the North.

Thus, Tamils in the north find that they don’t even have the right to remember and grieve in the new kind of “liberation” they have been dished out.

15. Ethnic and north – south polarization; rejection of Rajapakse government at successive elections in the North:

Three separate elections, namely presidential, parliamentary and local bodies, were held across the country including the North in 2010-2011. None of the three elections could be termed free and fair, with election monitoring bodies reporting intimidations, killings, attacks, and threats and massive abuse of state resources and state media before and during elections. However, the incumbent regime hastened to assure Sri Lankans and the international community that elections were indeed free and fair. Thus, in elections that the incumbent regime insisted was free and fair, the regime led by President Rajapakse suffered heavy defeat in three successive elections in the Tamil dominated Northern Province, including in areas that were previously controlled by the LTTE. The last of these elections, the local government elections in Jaffna, Mullativu and Killinochi saw unprecedented campaigning by the President himself, members of the parliament including the President’s influential brother and son, and other senior ministers. Material assistance and economic development was promised and generously dished out to desperately improvised communities who had their properties and livelihoods destroyed during the war. However, all these failed to convince the Tamil citizens, who voted overwhelmingly for the Tamil National Alliance, the leading Tamil party. However, in Sinhalese dominated areas of the country, the Rajapakse regime won overwhelmingly, with the main opposition United National Party and other smaller opposition parties suffering heavy defeats.

The elections results amply demonstrated the continuing polarization between the North and the South in relation to political aspirations of Tamils. In the northern local elections, government politicians and their supporters campaigned on basis that since they hold the all powerful executive presidency and more than two thirds power in the national parliament, the only way for improvised northern Tamils to rebuild their lives would be to vote for the government in the local elections too. The rejection of this by the Tamil voters, in one way could be interpreted as an assertion that their identity and political aspirations were important more than economic development even in the most desperate of circumstances. From another perspective, it was an assertion that Tamils in the north didn’t consider the brutal war waged by the Rajapakse regime that defeated the LTTE, as a “humanitarian operation” that “rescued / liberated” them (Tamil civilians) from the clutches of the LTTE.

Even after these overwhelming victories in the North and East in the parliamentary and local elections held in April 2010 and July 2011, the TNA is given very little opportunity to actively participate and contribute their perspectives towards development of the region, with the Rajapakse clan and the military determining policy and practice. Thus, there appears to be little prospect that the Tamil National Alliance’s parliamentarians and local government representatives elected by popular vote in the North could wield much influence in decisions that affect the life of Northern peoples.

Thus, a regime that was rejected at three successive elections by popular vote will continue to govern the North and make decisions about priorities that affect the life of people there. This could only change in the longer term with constitutional changes that will provide for significant power sharing and autonomy for the North. In the short term, the only way the popular vote will have a meaning in day to day governance would be if the Sinhalese dominated central government will agree to involve the elected representatives of the North and East in making decisions and determining policies and practices that affect the life of the people there and drastically reduce the military presence and stop the military from interfering in civilian life.

16. Way forward:

As mentioned at the outset, the restoration of normalcy to the North, enabling Northern people to live without fear and in dignity, with equal rights, freedoms, opportunities as their brothers and sisters in the rest of the country will serve as a key to lasting peace and reconciliation in the whole country.

In this regard, a key element will be reduction of the military presence in the north, reducing the role of the military and the restoration of civilian rule. Removal of restrictions on travel, fishing, freedom of association, assembly, expression, movement along with guaranteeing of the right to dissent, grieve, mourn, remember those killed and disappeared, build memorials for dead and disappeared will also be crucial indicators. The stopping of acts that have direct and indirect connotation of Sinhalese – Buddhist domination, ensuring that sign boards, official forms etc. are also in Tamil language, stopping land grabbing and reparation for victims and their families (those who had been killed, disappeared, injured, tortured, detained for long periods without charges, sexually abused, whose houses and land was occupied etc.) are also key steps towards reconciliation.

Accountability for violations that have happened, both in the last phase of the war as well as throughout the three decades of war, and post-war, including some incidents mentioned above, is also crucial. A process of truth telling which involves acknowledges the wrongs that have been done, identifies perpetrators would be essential, even to consider measures such as forgiveness and amnesty.

Recognition of historical grievances and political aspirations of the Tamil community, that led to the birth of the LTTE and other armed Tamil groups leading to three decades of war, and concrete and credible steps towards addressing these would be the another important element that we believe is crucial for Sri Lankans to move on to be able to live with each other without notions of enemy. Given the polarization amongst the Tamils and Sinhalese communities, as evident by starkly contrasting election results in the North and South as well as reactions to the end of the war, such a process is bound to be long drawn out and difficult. However, in the short term, what would be crucial is for the process to be seen as genuine and not leading to yet another initiative that would be abandoned. The support the present regime enjoys amongst the Sinhalese population makes it well placed to undertake such a process, and good starting point might be to resurrect the All Party Representative Committee (APRC) process that this regime itself initiated.

In the end, reconciliation and lasting peace will come through meaningful actions such as ones outlined above, rather than empty promises.

Tamils had formed the majority in the North, with significant Muslim and Sinhalese population as well, but the LTTE forced the Muslims to leave the North in 1990 and almost all Sinhalese who had been living in the North also left the areas in 1990s.

Control of the A9 road, the main highway running through the middle of the Northern province linking the Jaffna peninsula to rest of the country, was a prized possession that LTTE and Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) fought repeated bloody battles, with control switching sides several times, until GOSL forces took control of the highway in early 2009, few months before the military defeat of the LTTE. The regular closure of the highway and restrictions such as military passes to travel south, imposed by both the LTTE and GOSL had brought untold hardships to Tamils in the North and the opening of the highway between 2002-2006 for regular traffic and most recently in December 2009 were seen as symbolic opening up of the North.

It was in the North Eastern coastline of the Mullativu district that GOSL forces finally militarily defeated the LTTE and brought the whole of North under the control of the GOSL in May 2009. This was after long drawn out bloody battle which saw huge civilian and military casualties, entire villages and districts uprooted with people on the Western coast compelled to flee to the Eastern coast, houses and infrastructure totally destroyed.

By 2008, the GOSL had launched their final offensive to defeat the LTTE in the North. During 2006-2009, it is difficult to recall a day where extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrest, and torture from the GOSL controlled North were not reported. Restrictions on fishing, travel, communication and night time curfews were also imposed in the GOSL controlled parts of the North, together with an economic embargo. The LTTE imposed their own travel restrictions and other forms of repression in the districts they controlled, particularly forcible recruitment, including of children. Travelling was a nightmare, with multiple checkpoints where you had to get off buses with baggage, register yourself and have your body and baggage checked. No vehicles were allowed to cross through the fortress like Medawachiya checkpoint that separated the North from the rest of the country. There were times when we were told we couldn’t board trains bound for North from Colombo with a laptop and any laptop or camera would be opened up and checked even when they were allowed. It took hours to get pass the check points at the Medawachiya train station, the one hour flight to Jaffna often involved more than 10 hour journey and once the flight was cancelled for unknown reasons after a wait of 11 hours.