Ten years after the end of Sri Lanka’s civil war,all ethnic communities living in the border areas of the conflict zone appreciate having a level of security. However, they do not consider the country to be at peace;ethnic/religious divides remain damagingly strong and people feel utter despair over continuing economic difficulties and political failures. National minorities, Tamils and Muslims, feel discriminated against and oppressed by the state and targeted by Sinhala Buddhist nationalist politics. Sinhalese feel the state has neglected them while unfairly benefitting minorities. The feelings of marginalisation and neglect experienced by all groups are at times expressed as anger towards the ethnic/religious ‘other’ which exacerbates tensions and divisions.

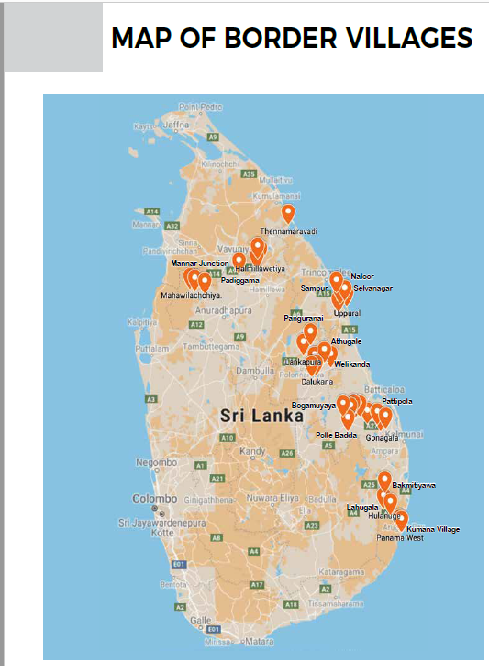

All these communities suffered intensely through the civil war. Because of the specific geography and demography of the ‘border villages’, violations were severe; targeted at civilians and few were spared. Even if the violations took place decades ago, memories are vivid, emotions are strong and as the interviews made clear,not dealing with the grief has not taken it away.

Transitional justice, both conceptually and as a process initiated by the government and international donors, means nothing to most people but claims for justice are strong among Tamils, less so among Muslims, and least among Sinhalese. The Sinhalese believe that the destruction of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) was a form of justice, which in itself underscores the need for post-war justice for other communities. Many felt peace is unachievable without justice.The strongest appeal from all three communities is in relation to their everyday survival; income generation, livelihood and development of their villages, which they see as a priority. Justice means different things to different people and is not disassociated from these everyday needs.

There are specific issues that affect this area that have not made it onto the national agenda, yet need to be urgently dealt with. These include: drought affected farming; high levels of debt; unemployment; kidney disease; elephant-human conflict and early marriage.Land related problems cut across all communities.

Whilst this research explores issues and aspirations of a very specific demographic group in a unique geographical area, there are nevertheless a number of larger conclusions of relevance to Sri Lanka as a whole that can be drawn from here. These include:

Whilst this research explores issues and aspirations of a very specific demographic group in a unique geographical area, there are nevertheless a number of larger conclusions of relevance to Sri Lanka as a whole that can be drawn from here. These include:

– Despite the end of the war, ethnic and religious divides remain strong and insufficiently resolved in some areas and contexts, with the potential to develop into small scale conflicts or fuel existing national conflicts.

– Peace building and reconciliation is not occurring in an organised and structured manner at the local level, though some communities are working on co-existence.

– Media and social media are playing a damaging role in strengthening divisions.

– Co-existence by default (because of the specific geography and demography) has resulted in some level of empathy for the ethnic/religious ‘other’, and a framing of difference as political rather than communal (by blaming the LTTE and politicians rather than Tamils and Sinhalese).

– Distrust of Muslims is strong amongst both other ethnic groups, though there is some recognition of Muslims having helped each group during the conflict.

– The feeling of discrimination and neglect over ‘everyday issues’, which the government could more easily respond to, manifests in anger for the ethnic/religious other, and is deepening ethnic/religious fissures.

– Peace building and reconciliation is not occurring in an organised and structured manner at the local level, though some communities are working on co-existence.

– Media and social media are playing a damaging role in strengthening divisions.

– Co-existence by default (because of the specific geography and demography) has resulted in some level of empathy for the ethnic/religious ‘other’, and a framing of difference as political rather than communal (by blaming the LTTE and politicians rather than Tamils and Sinhalese).

– Distrust of Muslims is strong amongst both other ethnic groups, though there is some recognition of Muslims having helped each group during the conflict.

– The feeling of discrimination and neglect over ‘everyday issues’, which the government could more easily respond to, manifests in anger for the ethnic/religious other, and is deepening ethnic/religious fissures.

Despite the geographic limitations of this study, it offers important new insights into the future of post-war reform in Sri Lanka. Primarily, it challenges dominant narratives: the role of perpetrators (whether Sri Lankan military or LTTE) in the armed conflict; the Sinhala and Tamil nationalist positions of victimhood in the conflict, and the relationship between peace and justice and the role of the state in the conflict and its aftermath. Secondly, the findings on the understanding and perceptions of the ethnic/religious other offer critical opportunities for peace building and reconciliation.

READ FULL REPORT as a PDF:The Forgotten Victims of War – A Border Village Study – FINAL