|

| The Rajapaksa regime has outlived its purpose and it should go |

By Laksiri Fernando

“Even in peacetime the world has an awful lot of problems. Only in peacetime can we get on with solving them.” – Bill Oddie

After the end of the war against the LTTE, ethnic reconciliation with all minorities, the Tamils and the Muslims alike, and also between them undoubtedly was the priority. There was no justification of the war otherwise. Development was necessary in parallel, but not as a substitute for or instead of reconciliation. The policy of the Rajapaksa regime, as it has turned out to be, is not reconciliation but assimilation. Reconciliation is only by words but not by deeds. This is already resisted by the minorities. The forthcoming provincial council elections in the East will sure to confirm this assertion.

There may be some who believed or believe that the war against the LTTE was wrong or it was wrong because the Rajapaksa regime was wrong. The reasons rightfully given are corruption and family rule, some of the perennial ills of many regimes. This is political puritanism and not political realism. ‘Conditional support’ to the regime was necessary to get rid of the LTTE and pave the way for the sustainable resolution of other problems such as ethnic reconciliation, democratisation, corruption, family rule, rule of law and human rights. These were not easily pursued during the war. Resolution of the ethnic conflict with the LTTE through peace negotiations was almost impossible as proved through experience and that is why the war could be supported or allowed conditionally without supporting human rights or humanitarian law violations. At least that is what the regime overtly promised, a humanitarian operation.

For a long period of time, Sri Lanka’s major political problem has been what can be called the ‘democratic revolution.’ Without this breakthrough, genuine or people centred development would not be achieved. This is the case even now. While the LTTE was a product of the lacunae or the delay of the democratic revolution, its appearance in the political stage also created a major obstacle for the democratic transformation. A victory of the LTTE could have belated the democratic revolution in Sri Lanka for many more decades. That is why a ‘two stage revolution’ or process was necessary. Now the first stage is over with the demise of the LTTE, the second stage of getting rid of the Rajapaksa regime should begin. It is already on the move.

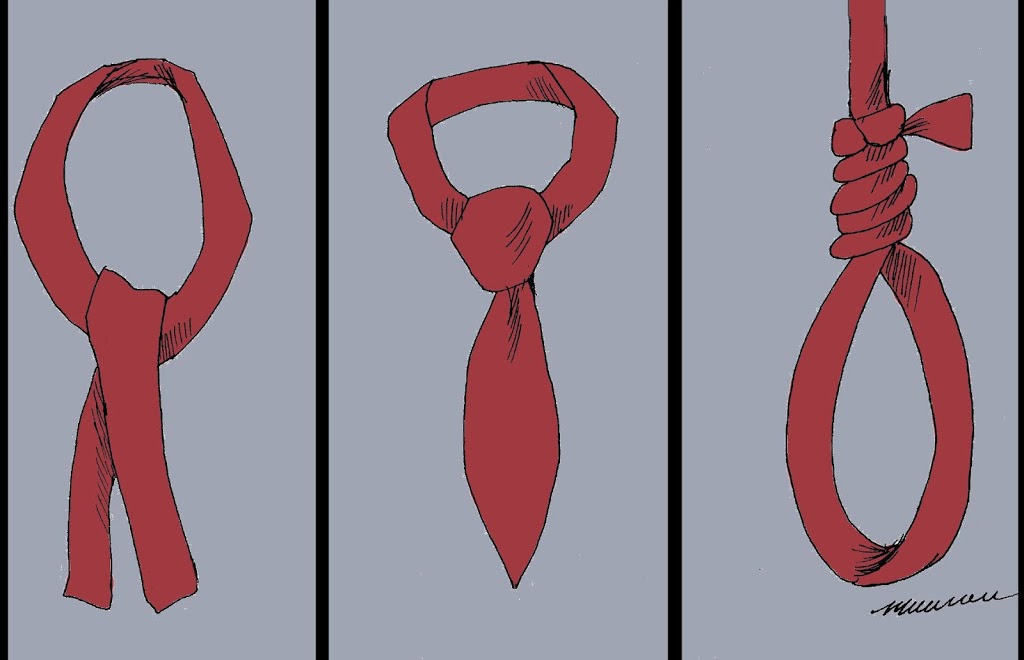

There were people who believed that the LTTE could not be defeated. They were proved wrong. There are people who believe that the Rajapaksa regime cannot (or easily) be defeated. The adverb ‘easily’ reveals certain defeatism. They would be proved wrong in the coming future. It took three years to defeat the LTTE in the battle field. It might take an equal period of time to defeat the Rajapaksa regime in the political field. The first trajectory primarily appeared to be a military conquest. But the second should be a peaceful political conquest given the parliamentary arena that the regime is primarily based. Sri Lanka also should not go into violence again. The defeat of the LTTE was not only military, it should however be noted. Political de-legitimisation amongst the Tamil people was its real defeat.

The 18th Amendment has been the Rajapaksa regime’s ‘mortal sin’ after winning the war. That was in September 2010. It exposed its character. It alienated many influential sections of professional groups in the country although not immediately. By that time many ills of family rule and corruption also had surfaced.

For the Tamil community, the ‘mortal sin’ of the regime of course is war crimes during the war. There will be no easy escape for the regime from these crimes. The horror of these events will never allow the Tamil community to reconcile with the Rajapaksa regime. It may be necessary to get the maximum possible out of the present regime for the minority communities under international and the UN pressure. But a proper reconciliation would be near impossibility without a regime change. No mediation could galvanize it. The regime has crossed the red line.

There may be some who believe that the regime cannot be changed easily because of its development drive. But day by day it is exposed to be hoax. When the people in the war ravaged North and the East first need basic infrastructure for livelihood efforts, priority is given for major roads and tourist hotels. The main reason is the commissions given by the big contractors. This is the same in the South and other areas as well.

Development may be measured by growth rates for a while. But the people would soon realise that the benefits mainly flow only to a certain class in society and not to them. The income disparities are enhancing and the poor is getting poorer and poorer. This is unbelievable for a regime headed by Mahinda Rajapaksa, who was believed to be a people’s man in the past. The only lifeline between the regime and the general masses seems to be few handouts given to them through programmes such as Samurdhi and others during election times. These are just to keep them alive on the poverty line.

Then what keeps the regime going? Of course, there are time sequences for electoral change. It is only two years since the last elections. Until people are sure that the time is ripe for regime change, particularly those who are dependent on handouts might hang on to the regime out of desperation. This is a predicament of a ‘poor democracy’ like in Sri Lanka. There are of course other reasons. Patriotism is one. The regime is portraying the LTTE still as a security threat. This is something which needs to be exposed. The Opposition is also weak. It is not in disarray like in the past but weak.

The readily available forces for regime change of course come mainly from the UNP and the TNA support bases. The JVP is also an important or crucial element in catalysing change among others. Hopefully, they will not make the past mistakes by indulging in violence. If they do, the upper hand and the legitimacy will go to the regime. Of course, the regime should be resisted, but resisted through the all available legitimate means.

The crucial ingredient is the winning over the UPFA support base for a sustainable regime change. Chandrika Kumaratunga can play a crucial role in this respect if she speaks now, and speaks forcefully. Similarly important is Sarath Fonseka, who might be able to break the deception of regime’s bogus patriotism, being the former army commander. Keeping the soldiers neutralized in any confrontation instigated by the regime is also important.

There are suggestions for a single issue common candidate for the presidency against Mahinda Rajapaksa. It is simply too early to identify a candidate now. Of course, there should be a firm commitment to abolish the presidential system from whoever is going to be the common candidate from the Opposition in the future. But, a single issue might not be the best approach. There are so many issues that a regime change should entail. There are valid arguments that a regime change per se is not enough; a system change is necessary. Of course, Kumar David has suggested a system change in the constitutional sphere which might or might not bring a systemic change in the other spheres.

A regime change is a social process involving the various layers and sections of society. It should be a comprehensive ‘socio-democratic’ programme and platform as much as possible. These issues should evolve and arise like in the FUTA struggle for saving the country’s educational system. We can debate upon them in advance but we should not completely predetermine them.

So far there are two sections of society that have moved against the regime in a purposeful manner: the academia and the legal profession. Although short-lived, the protest of the legal professionals, both judges and lawyers, against the attack on the Mannar Magistrate is significant like the FUTA strike. To me, these are the first signals of a democracy or a human rights movement. Intellectuals and lawyers have always been in the forefront of democracy struggles throughout the world. This is almost like a ‘textbook’ case. The two issues that they have raised are the independence of the judiciary (with rule of law) and the right to education. The education sector might be the Waterloo of the Rajapaksa regime. There are pressing issues of minority rights and working class issues. There is a need to crystalize them. This would also not mean that everything is rosy or would move smoothly.

At this very moment there are dangers to the FUTA struggle. There can be dismissals of FUTA leaders before reopening the universities. Then there will be legal battles. There can be temporary setbacks but more profound forward struggle in the future. What might be necessary is to call the spade a spade. The Rajapaksa regime has outlived its purpose and it should go.

IS