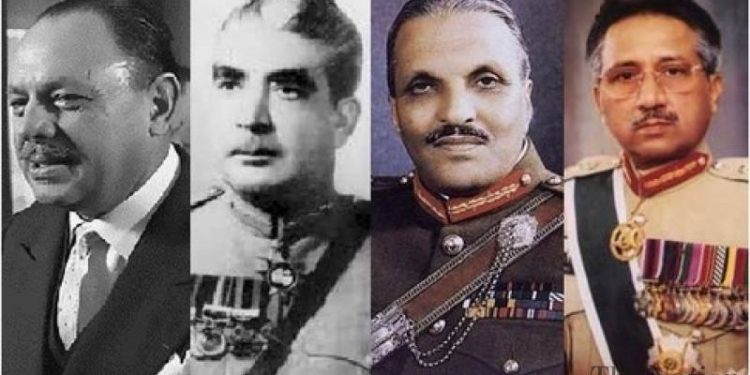

Image: Pakistani-military-ditators-Gen.Ayub-Khan-Gen.Yahya-Khan-Gen.Zia-ul-Haq-Gen.Pervez-Musharraf (NewsinAsia)

The doctrine of necessity was first expounded in the 13th century by English jurist Bracton, who stated ‘that which is otherwise not lawful is made lawful by necessity’. Glanville Williams described the defence of necessity as involving ‘a choice of the lesser evil. ‘

The doctrine is recognized in criminal law. For example, section 74 of our Penal Code gives the following illustration: ‘A in a great fire pulls down houses in order to prevent the conflagration from spreading. He does this with the intention, in good faith, of saving human life or property. Here, if it be found that the harm to be prevented was of such a nature and so imminent as to excuse A’s act, A is not guilty of an offence.’

[title]What happened in Pakistan[/title]

Because of its express recognition, with such illustrations, chances of the doctrine being abused in matters of criminal law are less, also because there is at least one appeal available to a higher court. The danger is with its application in constitutional law when a matter is decided almost always in the highest court of a land, as happened in Pakistan.

In Re the Reference by the Governor General (PLD 1955 FC 435), the Pakistani Federal Court quoted Cromwell as saying ‘[i]f nothing should be done but what is according to law, the throat of the nation might be cut while we send for someone to make the law.’ But Cromwell was aware of the danger of abuse of the doctrine. He stated in Parliament on 12 September 1654: “Necessity hath no law. Feigned necessities, imaginary necessities…are the greatest cozenage men can put upon the providence of God . . ..”

S. A. De Smith, having seen the doctrine being prostituted in Pakistan, stated in his Constitutional and Administrative Law (3d ed. 1977, p. 502) that the necessity must be proportionate to the evil that is to be averted and acceptance of the principle does not normally imply total abdication from judicial review or acquiescence in the supersession of the legal order.

This paper is about how the doctrine paved the way for the destruction of democracy in Pakistan, from whose experience Sri Lanka has much to learn. The immediate reason for writing this is the call from pro-government lawyers to emulate what happened in Pakistan. What is worse is the attempt at eulogizing Chief Justice Munir, who introduced the doctrine to Pakistan and who has rightly been labelled ‘the destroyer of democracy in Pakistan’.

[title]Dissolution of Constituent Assembly[/title]

At independence, the Government of India Act, 1935 was the basic law of both India and Pakistan. Their respective Constitutional Assemblies (CA) were also the legislatures. While the Indian CA produced a constitution by November 1949, things dragged on in Pakistan. The untimely death of Jinnah and the assassination of Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan also contributed to the slow pace. On 21 September 1954, the revised report of the Basic Principles Committee was approved by the CA and the draft of the constitution was ready to be announced on December 25, 1954, Ali Jinnah’s birthday. But Governor General Ghulam Muhammad dismissed the CA on 24 October 1954 claiming that the CA had lost the confidence of the people and that the constitutional machinery had broken down. The real reason, though, was that the draft proposed the curtailment of the Governor-General’s powers, including, importantly, the power of dismissing the Government of the elected Prime Minister.

The dissolution was successfully challenged in the Sindh High Court. The writ jurisdiction of the High Court had been granted by section 223-A introduced to the Government of India Act by the CA in July 1954. This was one of the forty-six pieces of legislation passed by the CA since independence. The laws were not assented to by the Governor General but were signed into law by the President of the Assembly as provided by the CA Rules. The Government claimed that section 233-A was invalid as it had not received the Governor-General’s assent. The High Court rejected this argument, stating the provisions of Independence Act left no room for any manner of doubt that the CA was a sovereign body and not subject to any checks and balances, restraints and restrictions.

The Government appealed to the Federal Court headed by Munir CJ. The Federal Court, in Federation of Pakistan v Moulvi Tamizuddin Khan, allowed the appeal, with Cornelius J dissenting. Munir CJ did not consider the issue of the legality of the dissolution but decided that it was imperative that a law enacted by the CA should be assented to by the Governor-General. Thus, section 223-A was null and void and the Sindh High Court had no writ jurisdiction.

[title]Necessity invoked[/title]

The judgement also meant that not only section 233-A but also the other forty-five laws enacted by the CA were void. The Governor-General then sought to validate the Acts, except section 233-A, by indicating his assent with retrospective operation, but the Federal Court in Usif Patel v The Crown, declared that this could not be done.

The Governor-General then made a Reference to the Federal Court seeking its opinion on the matter (Re the Reference by the Governor General, PLD 1955 FC 435). The Federal Court, divided three-two, held that the Governor-General has during the interim period the power under the common law of civil or state necessity of retrospectively validating the laws concerned until the question of their validation is decided upon by a new Constituent Assembly.

Munir CJ invoked the doctrine of necessity in support of the decision of the majority. He relied on passages in an address to the jury (thus, in a criminal case) by Lord Mansfield that subject to the condition of absoluteness, extremeness and imminence, an act which would otherwise be illegal becomes legal if it is done bona fide under the stress of necessity, the necessity being referable to an intention to preserve the constitution, the State or the society and to prevent it from dissolution. Chitty’s statement that necessity knows no law and the maxim cited by Bracton that necessity makes lawful which otherwise is not lawful were also cited. Since Lord Mansfield’s address expressly refers to the right of a private person to act in necessity, in the case of Head of the State justification to act must a fortiori be clearer and more imperative, Munir CJ stated.

In the result, what Chief Justice Munir did was to effectively validate the dissolution of the CA and let all the other laws enacted by the CA to continue. But this was to be just the beginning of Munir’s contribution to the destruction of Pakistani democracy.

In 1955 itself, Ghulam Muhammad was deposed by Major General Isakander Mirza with the support of members of the new CA.

[title]Legitimising military rule[/title]

State v. Dosso (PLD 1958 SC 533) concerned four appeals from the High Court of West Pakistan. They were listed for argument before the Supreme Court on 13 and 14 October 1958. The main issue before the Court was the legality of the Councils of Elders in the tribal areas of the North Western Frontier Province which were given criminal jurisdiction under the Frontier Crimes Regulation, 1901. The respondents had succeeded in the High Court which held that the relevant Regulation offended fundamental rights guaranteed by Article 5 of the new Constitution of 1956.

Six days before the hearing, on 07 October 1958, President Mirza annulled the Constitution by Proclamation, dismissed the Central Cabinet and Provincial Cabinets and dissolved the National Assembly and both Provincial Assemblies. Martial Law was declared and General Muhammad Ayub Khan, Commander in Chief of the Pakistan Army, was appointed Chief Martial Law Administrator. Three days later, the President promulgated the Laws Continuance in Force Order, the general effect of which was the validation of laws, other than the 1956 Constitution, that were in force before the Proclamation. The Order contained the further direction that the country shall be governed ‘as nearly as may be’ in accordance with the 1956 Constitution.

The main issue now before the Supreme Court was the legal validity of the new regime. Would Article 5 of the 1956 Constitution still apply? In other words, was the abrogation of the Constitution valid? On the day the judgment in Dosso was due, in the early hours of 27 October, Ayub Khan struck, forcing Mirza out and later packing him off to London. Munir CJ placed the stamp of legality on the military regime, as he did for Ghulam Muhammad’s dismissal of the CA. He relied on Kelsen’s theory of revolutionary legality. In Kelsen’s view, since the principle of legitimacy is grounded in the grundnorm (the basic norm), a revolution or coup, which sets aside the basic norm, denudes the entire legal order of its validity. A successful, or efficacious, revolution thus puts in place a new grundnorm from which the entire legal order must derive its legitimacy.

Munir CJ held that the revolution having been successful, it satisfies the test of efficacy and becomes a basic law creating fact. On that assumption, the Laws Continuance in Force Order, however transitory or imperfect it may be, is a new legal order and it is in accordance with that Order that the validity of the laws and the correctness of judicial decisions has to be determined.

It is hard to see how, in a case that was heard within six days of the promulgation of Martial Law and within three days of the promulgation of the Laws (Continuance in Force) Order, Munir could hold that the new regime satisfied the test of efficacy. Indeed, as counsel in the 1972 Asma Jilani case would point out: ‘It was too early yet to hazard even a guess as to its efficacy. Indeed, had the learned Chief Justice waited a few more days he would have seen that the efficacy was non existent. This was more than amply demonstrated by the removal of the so called successful law creator himself the very next day after the publication of the judgment of the Court. Where then, it is said, was “the essential condition” for the recognition of the change?’

[title]Asma JIlani, SC rejects ‘necessity’[/title]

Ayub Khan promulgated a new Constitution on 01 March 1962 which came into effect on 08 June 1962. Unable to deal with the growing unrest in East Pakistan, Ayub handed over power to the Army’s Commander-in-Chief, General Yahya Khan on 24 March 1969. Yahya Khan imposed martial law two days later and abrogated the 1962 Constitution. He appointed himself President and Chief Martial Law Administrator. On 04 April 1969, a Provisional Constitution Order was enacted whereby the Constitution of 1962 was by and large restored, and it was provided that the country was to be governed as nearly as may be in accordance with its terms but subject to the Proclamation of Martial Law and to any Regulation or Order that may be made from time to time by the Chief Martial Law Administrator.

After the defeat of Pakistan in the Bangladeshi war Yahya Khan resigned on 20 December 1971 and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the leader of the Pakistani People’s Party, took over both positions.

The validity of the Yahya Khan regime came up for decision in Asma JIlani v. Government of Punjab (PLD 1972 SC 139). The High Court, relying on State v Dosso, held that the Order of 1969 was a valid and binding law and that it had no jurisdiction in the matter.

The Supreme Court declined to follow Dosso. Hamoodur Rahman CJ stated that ‘Kelsen’s theory was, by no means, a universally accepted theory nor was it a theory which could claim to have become a basic doctrine of the science of modern jurisprudence, nor did Kelsen ever attempt to formulate any theory which “favours totalitarianism”.’ Kelsen’s theory is a descriptive theory of law and not a normative principle of adjudication.

The Chief Justice agreed with the criticism that Munir CJ not only misapplied Kelsen’s doctrine but also fell into error in thinking that it was a generally accepted doctrine of modern jurisprudence. ‘Even the disciples of Kelsen have hesitated to go as far as Kelsen had gone.’ Dosso’s case does not lay down good law, and must be overruled. The military rule sought to be imposed upon country Yahya Khan was declared not only invalid and illegitimate but also incapable of being sustained even on ground of necessity.

The Asma JIlani judgement was followed by the removal of Martial Law, the interim Constitution of 1972 and then by the new Constitution of 1973 under which Pakistan reverted back to a Parliamentary form of government. Bhutto became Prime Minister. In July 1977, General Zia-ul-Haq overthrew Bhutto, imposed Martial Law and abrogated the 1973 Constitution.

[title]SC rules military take-over ‘necessary’[/title]

The legality of Zia’s regime came up for decision in Begum Nusrat Bhutto v. Chief of Army Staff (PLD 1877 SC 657). The Court held that Kelsen’s theory was not applicable. One would have expected the Supreme Court to decide on the legality of the change. Instead, the Court went to hold, relying on the doctrine of necessity, that the military overthrow itself was necessary!

Zia, like the dictators before him, ruled with an iron fist until August 1988, when he died in a plane crash. His death paved the way for the restoration of democracy and elections in December that year. There was relative peace for about a decade until the Army struck again in October 1999, this time under the leadership of Musharraf, who ruled until August 2008 when he was forced to resign. At the Parliamentary elections held in February 2008, his party was badly defeated.

[title]‘Necessity’ buried[/title]

In Syed Yusuf Raza Gilani, Prime Minister’s case (19 June 2019), the Supreme Court refused to resurrect ‘the malignant doctrine of necessity which has already been buried, because of the valiant struggle of the people of Pakistan.’ When Musharraf was tried for high treason (Federation of Pakistan v. General (R) Pervez Musharraf, 17 December 2019), the issue of the legality of his actions came up before the Special High Court which refused to invoke the doctrine of necessity to validate his actions. Referring to Munir CJ’s original invocation of the doctrine, the Special High Court stated: ‘Had the hon’ble Superior Judiciary, at that time, not invoked the Doctrine of Necessity, and had proceeded against usurpers, abrogaters, subvertors, the Nation would not have seen this day at-least, where an office in uniform repeats this offence’.

Addressing a judge’s conference on 02 February 2019, the then Chief Justice of Pakistan, Mian Saqib Nisar said that the infamous doctrine of necessity that had given the judicial nod to successive martial laws in the country now lay buried. (Dawn, 04 February 2019).

Mark M. Stavsky in his paper on ‘The Doctrine of State Necessity in Pakistan’ warned against the dangers of the doctrine’s application in constitutional law: ‘Doctrinally, courts should be reluctant to permit deviations from constitutional norms. Approval must be reluctant because courts, in reviewing a state necessity claim, must consider the legitimacy of readjusting fundamental political, social, and legal values. This consideration must be made in cases where the challenged state action affects individual rights as well as in cases involving changes in the governmental structure.’ (Cornell International Law Journal, Summer 1983, 341 at p. 344).