Four years since the end of the armed conflict, the situation of minority women in the north and east of Sri Lanka has changed dramatically – and for many it is getting worse. In the latter stages of the conflict and its aftermath, military forces were responsible for a variety of human rights abuses against the civilian population, including extrajudicial killings, disappearance, rape, sexual harassment and other violations. In the current climate of impunity, sustained by insecurity and the lack of military accountability, these abuses continue.

Thousands have lost their husbands and other family members during the armed conflict. Others, such as those whose husbands and relatives surrendered to the army after the government’s announcement of an amnesty for former Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) personnel, still do not know their whereabouts and face an ongoing struggle for truth, justice and accountability. For many women, this has brought new responsibilities: 40,000 households in the north and east are now female headed.

Yet Sri Lanka’s social and political environment remains heavily patriarchal, exposing women to multiple levels of discrimination. Many now have added responsibilities as primary earners for their families: they face limited livelihood opportunities in the post-armed conflict context, and are typically excluded from official development programmes. Furthermore, against a backdrop of competing claims and mass resettlement, they are especially vulnerable to land grabs and other rights violations.

The militarization of the north and east from 2009 has contributed to continued insecurity for minority women. Many, especially widows and the wives of disappeared or ‘surrenderees’, are vulnerable to sexual harassment, exploitation or assault by army personnel or other militias. The military presence in the area, together with the increasing chauvinism of Sri Lanka’s political and religious hierarchy, has also reduced their cultural and religious freedoms – including their right to mourn their dead.

Resettlement in the north and east, not only by those displaced during the armed conflict but also through government-sponsored relocation of Sinhalese workers and households, has raised tensions between communities in the current divisive environment. This is the result not only of disputes over land and resources but also differing social and cultural norms. The increasing prevalence of sexual exploitation and relationships, coerced or otherwise, has put women on the frontline of these conflicts.

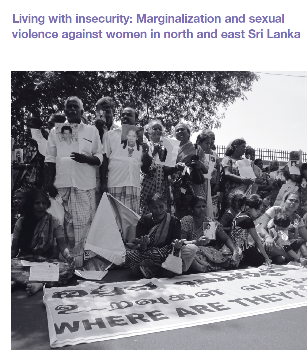

So far the government’s response to these ongoing rights violations has been inadequate. In fact, state and military policies are actively contributing to insecurity and the marginalization of women in the north and east. By contrast, women activists continue to advocate, often at great personal risk, for truth, justice and accountability for themselves and other survivors of the armed conflict. However, until a clear framework of protection is created for minority women and other marginalized groups, including physical security, freedom of expression and land rights, the possibility of lasting peace and reconciliation in the north and east remains elusive.

|

Box 1: Key findings

|

|

|

• Four years after the end of the armed conflict, the situation for minority women in the north and east of Sri Lanka remains deeply insecure. Thousands of women have lost husbands and other family members to death or disappearance, while human rights abuses and violations ranging from sexual violence to land grabbing continue.

|

• The government is actively contributing to insecurity and rights violations through the pervasive militarization of the north and east, with negative consequences for the safety and freedom of minority women. Poorly managed resettlement and competing land claims among the increasingly heterogeneous population are also raising tensions between different communities.

|

|

• Many minority women in the north and east are now the primary income earners for their households, yet these responsibilities have not been accompanied by improved rights or status. Besides the struggle to secure land rights or access local resources, they also face limited livelihood opportunities in the post-armed conflict context and have not been properly included

in official development programmes.

|

• Women’s activists continue to advocate, often at great personal risk, for truth, justice, accountability and an end to the climate of impunity that enables ongoing rights violations. However, until a clear protection framework is in place for minority women and other marginalized groups, the prospects of a lasting peace and reconciliation process will remain elusive.

|