(Lasantha Wickrematunge )

And Then ‘They’ Came For Him.

by Vimukthi Yapa.

But who is “they”? One household employee of Wickrematunge had harboured a suspicion that “they” were sent by former Defence Secretary Gotabhaya Rajapaksa, a suspicion that he had openly voiced. That suspicion did not win the employee a lawsuit or even the ignobility of a summary arrest for defamation. Instead, he was stopped on the street, hooded, gagged, tied up and abducted in one of the white vans synonymous with the former regime.

“If you ever speak of the secretary’s involvement in Lasantha’s murder, I will end your life,” the suspect allegedly said to his captive some seven years ago, as he was about to be blindfolded and returned to the place from where he was abducted. At the time, the victim, fearing for his life, hoped and prayed that they would never meet again. He could not have imagined the scene that would transpire last Wednesday, July 27, when fate would favour him, and he would be the one to physically lay a hand to the man he was to single out as his captor.

Last Wednesday morning, two vehicles made their way to the Mount Lavinia Magistrates Court, both carrying hooded passengers under armed guard. One of the vehicles is a regular to the court – the Black Maria transporting prisoners between Welikada Remand Prison and their hearings escorted by uniformed police. The other was an unmarked van travelling to the courthouse from the New Secretariat building in Fort, the headquarters of the CID.

On this day, the Black Maria carried Warrant Officer II Prema Ananda Udalagama, the army’s most senior non-commissioned spy, arrested ten days ago in a CID operation aimed at revealing the conspirators involved in murdering founder editor of The Sunday Leader Lasantha Wickrematunge.

The van carried CID detectives and a precious witness whose identity and whereabouts remain one of the most closely guarded secrets in the police. The witness had claimed that he was abducted and threatened against cooperating in the investigation into Wickrematunge’s murder, specifically threatened with death if he spoke of any involvement by former Defence Secretary Gotabhaya Rajapaksa. Among the reasons the CID arrested Udalagama: his description exactly matched that provided by the abduction victim.

Udalagama was to be produced before the victim in an identification parade, where the victim would have to pick him out of a line-up of nine individuals. The scene that transpired, however, bore little resemblance to identification parades seen in cinematic films, where the witness identifies the suspect in mere seconds. This parade ran for nearly twenty nerve-wracking minutes from start to finish.

At the outset, the magistrate was sensitive to allegations by counsel appearing for the accused, Udalagama, that the parade may have been “rigged” by the appearance of Udalagama’s likeness on various websites. In order to make the parade as balanced as possible, the magistrate permitted Udalagama to personally hand-select the eight individuals who would join him at the parade out of those present in court.

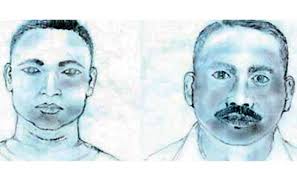

Udalagama, a veteran in the ways of espionage, had taken his own precautions. He had shaved off the moustache that he sported at the time of his arrest, and trimmed his hair. Availed the opportunity to choose the others in the parade, the intelligence officer picked out eight people who looked very similar to him, including two who matched his outfit of a short-sleeved blue shirt and dark trousers. The latter appeared so similar to the spy that several were suspicious that they had been planted in the courthouse by Udalagama’s colleagues in military intelligence.

Be that as it may, Udalagama was mixed among the eight others he had selected and presented before the witness by the magistrate. Initially, the witness paused, presented with nine similar looking individuals, too similar in appearance for his captor to be instantly singled out. The other participants in the parade stood motionless, for they had nothing to fear. If the witness had picked out the wrong person, they would not be arrested, but released, for there were no grounds to suspect any of them. It was only the accused, Warrant Officer Premananda Udalagama who had anything to fear, and fear he did, as the witness inspected the parade, walking up and down, studying the individuals before him for nearly twenty minutes under the watchful eye of the magistrate.

Suddenly, the witness froze. His eyes shifted furtively between the two individuals before him in blue, short-sleeved shirts and dark trousers, both dark in complexion, short haired and sans the moustache the witness had alleged was sported by his captor in 2009. One of the individuals had arrived that morning in the Black Maria, believed by the CID to be his captor. The other had arrived at the courthouse by other means. Few present would have been able to tell them apart in the second instance.

Eventually, the witness shook visibly as his gaze fixated on Udalagama. He turned towards the magistrate, then back towards the accused. With a visible tremor accompanying the courage of his convictions, the witness raised his arm and placed it squarely on the shoulder of the accused. “It was him,” he said. “He was the one.”

Udalagama stared coldly at his accuser, leaving few with any doubt that he would have liked nothing more than to fulfil the promise made by a kidnapper to his captive nearly seven years ago. The CID detectives present were clearly determined to ensure that neither the accused nor anyone in his formidable team of military intelligence operatives and paramilitary agents, was accorded any opportunity to do harm to the brave witness. Upon the conclusion of the parade and the magistrate’s order to remand Udalagama until the case is next heard on August 4, detectives spirited the witness away, changing vehicles and observing strict communication protocols and surveillance detection routines, dropping off their witness at a secure location before returning to CID headquarters.

While many have been interrogated and one arrested in the course of the investigation, there is a common thread binding all of the suspects together. They are all employees of the State. That common thread echoes the words Wickrematunge himself wrote in what The New York Times called his “letter from the grave,” his self-penned obituary.

“Murder has become the primary tool whereby the State seeks to control the organs of liberty,” Wickrematunge wrote. Indeed, the trajectory of the CID investigation leaves little doubt that several sectors of government are suspect of involvement in a wide-ranging conspiracy to assassinate Wickrematunge and shield his killers.

In the course of its inquiry, the CID has grilled a bewildering number of senior police officers, including a hitherto unheard of coterie of retired Deputy Inspectors General and Inspectors General of Police.

Former Senior DIG Prasanna Nannayakara was interrogated last year over the disappearance of evidence – the notebook in which Wickrematunge wrote down the motorbike license plate numbers of his assailants – and the alleged planting of evidence, as the CID gathered more and more evidence that he was complicit if not instrumental in both. The Mount Lavinia police who investigated the murder came under his jurisdiction. Former IGP Jayantha Wickremaratne was grilled for his suspected role in these same events.

Former DIG Chandra Wakista, then responsible for the TID, was questioned at length over several irregularities and inconsistencies in the TID’s handling of the investigation into Wickrematunge’s killing after the case was suddenly transferred to the TID in 2010.

Just this week, former Senior DIG Keerthi Gajanayake and former IGP Mahinda Balasooriya were raked over the coals over several matters including the circumstances under which the case was suddenly transferred away from the CID after less than three months, shortly after the CID had achieved a major breakthrough by identifying the involvement of Lance Corporal Kanagedera Piyawansa and thus the hand of military intelligence operatives in Wickrematunge’s assassination.

A week prior, a former Major General and former Director of Military Intelligence was secreted to CID Headquarters from Killinochchi to provide more information on the role played in the conspiracy by military intelligence operatives and defence officials at the highest level.

If the CID turns out to be correct in its apparent suspicions, the assassination of Wickrematunge would be the first such conspiracy in the country’s history to involve coordination by two successive IGPs, at least three DIGs, and military flag officers and non-commissioned officers and intelligence operatives at the highest level.

The fact remains, however, that for all its diligence and tenacity in the course of this inquiry, the CID appears to be almost consciously oblivious of two of the most critical components of an investigation into a plot with such unquestionable complexity and intricacy: the question of means, and the question of motive.

Specifically, how many people had the power and influence to orchestrate such a scheme, with sway to hold the strings of the most senior brass of the country’s military and law enforcement apparatus. Of that handful, how many had the motive and impunity to assassinate the Editor of The Sunday Leader, a close friend of a sitting wartime President, under a state of emergency?

More specifically, Wickrematunge was brazenly followed for hours across a capital city littered with police and military checkpoints, then brutally attacked in broad daylight on a busy street in a high security zone, within a stone’s throw of one of the country’s most heavily fortified Air Force bases. Who indeed, could have both masterminded such a plot, and engineered its cover up? Wickrematunge himself clearly foretold this puzzle, and taking his signature cryptic dialect beyond the grave, left us some clues in his letter from the grave.

His first clue was his apparent exoneration of his long-time friend, former President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

“I feel sorry for you,” he wrote, addressing the former President. “As anguished as I know you will be, I also know that you will have no choice but to protect my killers.”

The second was alleging in no uncertain terms that while the former President would not have had a hand in the killing, he would however know without doubt who masterminded it, and that he would have reason to fear that person. “We both know who will be behind my death, but dare not call his name. Not just my life, but yours too, depends on it.”

Wickrematunge also went so far as to address his alleged murderer personally. “I want my murderer to know that I am not a coward like he is, hiding behind human shields while condemning thousands of innocents to death,” he declared. “What am I among so many? It has long been written that my life would be taken, and by whom. All that remains to be written is when.”

This newspaper and others of the fourth estate have in the past attempted to pose answers to the question of who had the means and motive to murder Wickrematunge and the other journalists and parliamentarians slain between 2005 and 2014, strike fear in the heart of the President and orchestrate such a definitive and wide-ranging cover up. On each occasion we have paid a high price in blood and treasure, not least of which was the “supreme sacrifice” of Wickrematunge himself on January 8, 2009. It is high time that the CID and the government as a whole confront these difficult questions head-on, putting the “machinery of the State” in service of justice and the preservation of democracy. Power of such magnitude cannot be dispelled overnight by a “rainbow revolution” or “good governance.” It will take a concerted effort and political will to dislodge the vestiges of dictatorship entrenched across the security apparatus of the country. They should be under no illusions of whose lives will be at stake if these forces are afforded a chance to return and prevail.

Sunday Leader