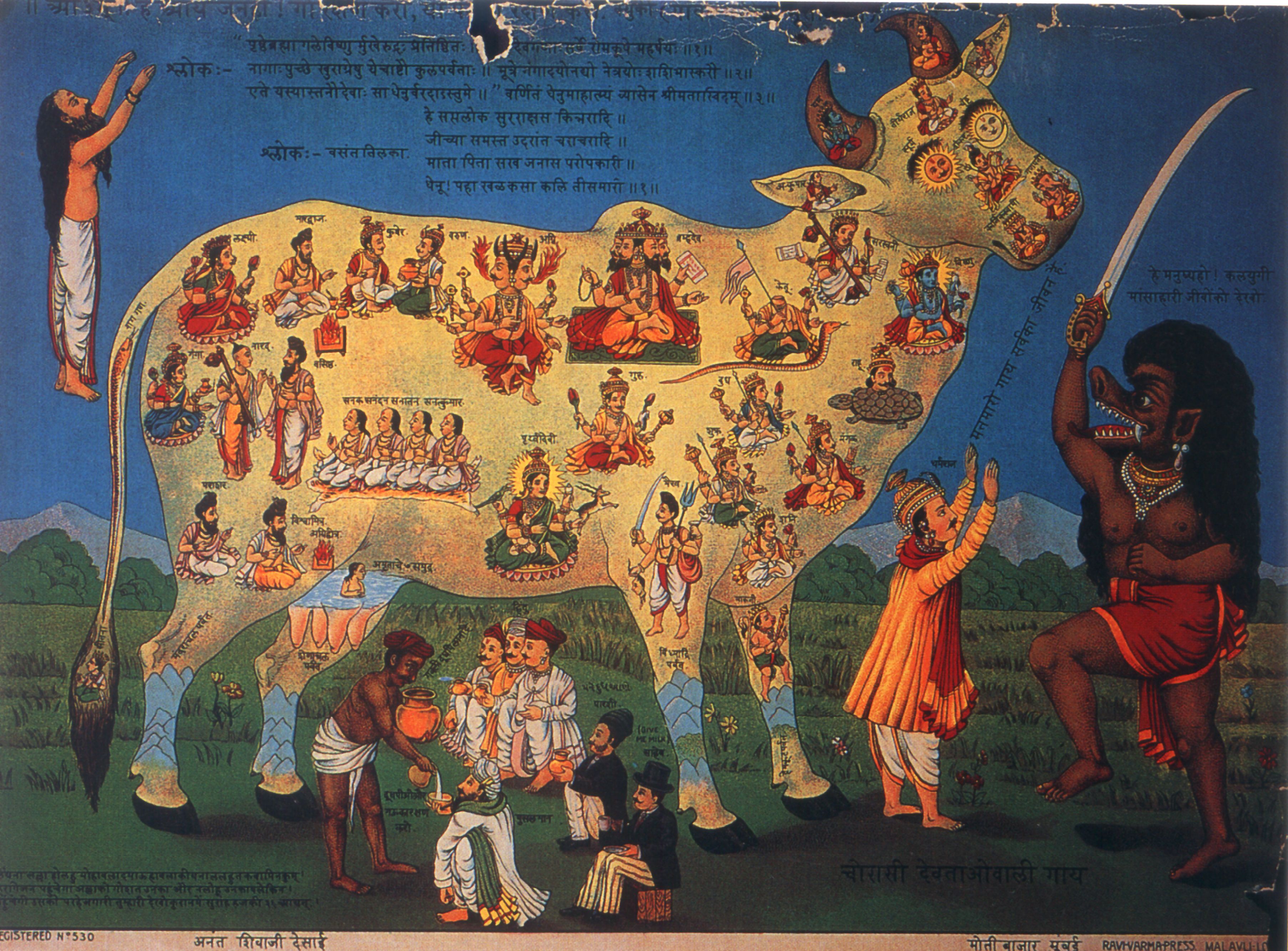

Image:Popular poster – Chaurasi Devataon-wali Gai [Ravi Varma Press – 1897]

By

The cow, the bull and the buffalo have waddled themselves into the centre of India’s politics, exposing its bovine underbelly.

The cow has been milked in Indian politics for over a century now; the bull has sharpened its horns over the past few years; and the buffalo has signalled its entry as a darkish symbol of counter-resistance, more recently.

It is the bull that has hogged the headlines in Tamil Nadu over the past few weeks. Ever since the harvest festival of Pongal (when the Sun enters the sign of Capricorn) on January 14 this year, a popular mobilisation saw hundreds and thousands of people in various cities of the state converge upon open spaces, like beaches and play grounds, challenging a Supreme Court order of 2014, banning the primarily rural practice of jallikattu.

Jallikattu is an annual sport among a couple of intermediary castes, restricted to a few southern districts of the state, like Madurai, Tiruchirapalli and Thanjavur. It involves letting loose a bull of high quality, indigenous, Kangeyam breed [kari maadu] into an arena, after having primed it up into a frothing rage through all sorts of injurious external incitements – including alcohol and chilli powder. The suitably agitated animal is then required to be held by its hump and subdued by young men of specific castes, who attribute tremendous valour to the deed and acquire social capital in their community, including eligibility to marry the girl of their choice. There is also the challenge and excitement of trying to remove a girdle of cash tied around the bull’s horn (from which the term jallikattu is derived), which could also be a decent addition to your pocket-money.

There are, perhaps, 300 breeders of such bulls in the State. On the appointed three or four days every year, 40 to 50 bulls are made to run through the vadi-vaasal (the entrance gate) to the arena, which is barricaded to protect the thousands of spectators who crowd in. The bull that remains the most ‘untamed’ is proclaimed the true stud and is eagerly sought in villages near and far to mate with local cows and sire pedigree progeny.

Ever so often, over the past decades, rather than being overpowered, the bull has gored many young aspirants to an early death. Even more tragically, the infuriated bulls periodically smash through the ramshackle barricades of the arena to inflict fatalities on bystanders. Many have lost their lives thus and others have died in resulting stampedes. Local sentiments have often papered over such tragedies and the ‘sport’ was conducted without any serious regulation. One of the reason was also the economics of high-volume betting that accompanied it – leading to a culture of silence around its negative fall-outs.

The Tamil Nadu Regulation of Jallikattu Act of 2009 was the first attempt to heed to several warnings from the courts regarding the need to regulate the unhealthy aspects of the practice. But, here too, specific exceptionalism was sought for by trying to project this form of bull-‘taming’ as a cultural value of the entire state, which was claimed to be at the core of Tamil identity since there were references to it even in classical literature in the language dating back to a couple of millennia.

Of course, none mentioned that it was hardly an ‘inclusive sport’, considering the Dalit communities were traditionally kept out of it. In fact, often the bulls were deliberately corralled to run into Dalit parts of the village, which legitimised youth from the upper castes invading those areas and ‘raiding’ Dalit houses, leading to protracted caste conflicts.

Appraised of the matter by a parent who lost his son in one such bull-run, the Supreme Court had looked askance at this practice, questioning its claims to constituting a ‘cultural heritage’ of the region. The court had been indignant about the implicit and explicit torture of the bovine and had sought to restrict its practice, extending the ambit of jurisprudence around human rights to apply to ‘non-human’ beings too. The 2014 Supreme Court judgment (Animal Welfare Board of India vs. A. Nagaraja) was rated among the more progressive legal acts in India.

The BJP government at the Centre, though, with an eye on reaping some electoral dividends in Tamil Nadu, sought to appease an agitated constituency by passing an executive order in early 2016 making jallikattu legal. This was promptly challenged in the Supreme Court, which forthwith stayed the order. A review petition by the TN government challenging the 2014 Supreme Court order too was dismissed by the court in November last year. So technically, jallikattu stayed banned in January 2017.

However, beginning from Pongal, the roughly 10-day-long mobilisation in favour of jallikattu and seeking a revocation on its ban, seemed to kick off several simmering discontents, leading to a social-media triggered convergence of issues including Tamil pride around tradition and heritage, anger against animal welfare organisations, including the AWB and PETA (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals), a general feeling of the Centre being insensitive to South Indian issues, a lingering sympathy for the Eelam (or Tamil homeland) movement of the LTTE in Sri Lanka (since brutally crushed by the Sri Lankan state) and the unarticulated, though subliminal, echoes of the historic movement for assertion of Dravidian identity beginning in the late 1920s, which culminated in the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) being voted into power in 1967. Interestingly, since then, the two main Dravidian parties – the DMK and the All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) – have by turn ruled the state for an unprecedented 50 years without a break.

The reaction of the ruling AIADMK government, which has been going through a leadership and credibility crisis since its charismatic chief minister J. Jayalalithaa passed away in December 2016, has been supine and demonstrative of a governance-deficit. The make-shift chief minister O. Panneerselvam, instead of going to areas where people were agitating and talking with them directly, rushed to Delhi to take Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s blessings for a new ordinance that would by-pass the Supreme Court’s ban order.

On January 22, he announced the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Tamil Nadu Amendment) Ordinance of 2017. This amends chapters III and V of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1960 (PCA, 1960), by which the deployment of bulls for purposes of fights, races and circus acts was deemed an act of ‘cruelty’. On January 23, when the Tamil Nadu legislature met at an emergency session and unanimously passed the ordinance, it became a new law by which it was no longer a crime or punishable offence to take the bull to a public space, pit it against hundreds of men, goad it with sticks, pull or bite its tail or ears, beat its hump, forcibly make it ingest alcoholic brews or insert chilli powder in its sensitive parts. Tamil pride had once again been reclaimed.

Even as both right wing and liberal voices in the media described the disciplined surge of popular emotion in gushy and ecstatic prose – some even dubbing it a ‘revolution from below’ – things turned sour as a more adamant section of the agitators turned violent, sending the Chennai police into an unprecedented display of savagery and brutality on the protestors and residents in adjoining fishing colonies. While the violence tainted the credentials of the movement, there is a faux patina of heroism being attributed to it. Yet none of the celebrity names from the film, sports and arts fraternity, who had rushed to endorse the ‘movement’, have opened their otherwise loud mouths to condemn the loss of four lives when jallikattu was conducted in a few places in defiance of the court order. There is neither a display of sympathy nor any visible move to raise funds for the bereaved families.

Not to be left behind, we are now seeing the beginnings of a Tamil Nadu style movement in neighbouring Karnataka, with a popular mobilization to ‘restore’ kambala or bull/buffalo racing. In Andhra Pradesh too, the cock-fight lobby has decided to cock-a-snook at animal protection laws as well as court orders.

Mahishasura Mardini – Durga slaying Mahisha, the Buffalo King – Popular calendar art – 1910

However, there are many unanswered aspects to the issue. This alignment of the claim to Tamil identity and pride through the symbol of the bull is reminiscent of the ‘cow protection’ battles in India which have been almost central to the Hindutva pitch for a Hindu nation state. Beginning with the inflammatory poster in the late 19th century called ‘Chaurasi Devataon-wali Gai’ (or the ‘Cow with 84 Deities’), which depicts a cow with Hindu deities residing in every part – from toe to horn to tail – being attacked by a ‘demon’ with a chopper, suspiciously resembling a Muslim or a Dalit, which set off a slew of court cases and came to be called the ‘Holy Cow’ case in the British press, to the recent acts of vigilantism across north India in the name of cow protection, which have also seen public floggings and lynching (till date unpunished) of Dalits and Muslims – the cow has been a great instigator in Indian politics right since colonial days. Inevitably, it has been the subject of some scholarly attention in the past decades, as a catalytic element in the violent discourse around Hindu nationalism.

An unusual variant surfaced in 2016, during the sequel to the right-wing assault on students and faculty at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, when the student faction of the ruling BJP accused other students in the university of desecrating the festival of Dussehra by memorialising it as a day when the Dalit Buffalo-king Mahishasura was deceitfully annihilated by the upper caste ‘agent’ Durga.

In the dominant narrative, the ‘divine’ Durga is depicted as slaying a recalcitrant demon. The Dalit assertion around the right to eat beef, combined with a thumbing-of-the-nose to mainstream constructions of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in Hindu mythology, which are heavily weighted in favour of the upper castes, has now brought India’s bovine politics to a fresh boil – what dissident scholar Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd has defined as the need for ‘buffalo nationalism’ to counter the majoritarian ‘cow nationalism’.

The cow, the bull and the buffalo are unlikely to disappear from mainstream Indian politics for some time.

Courtesy of the WIRE