Influential presidential sibling Basil Rajapaksa is tipped to be sworn in as a National List MP next week when his two-week quarantine after returning from a holiday in the United States ends. That would be the precursor to be appointed as the Minister of Finance of Economic Development, a portfolio currently held by Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa. The backbenchers of the ruling party, Sri Lanka PoduJana Peramuna (SLPP) are earnestly clamouring to resign en masse to make room for Basil.

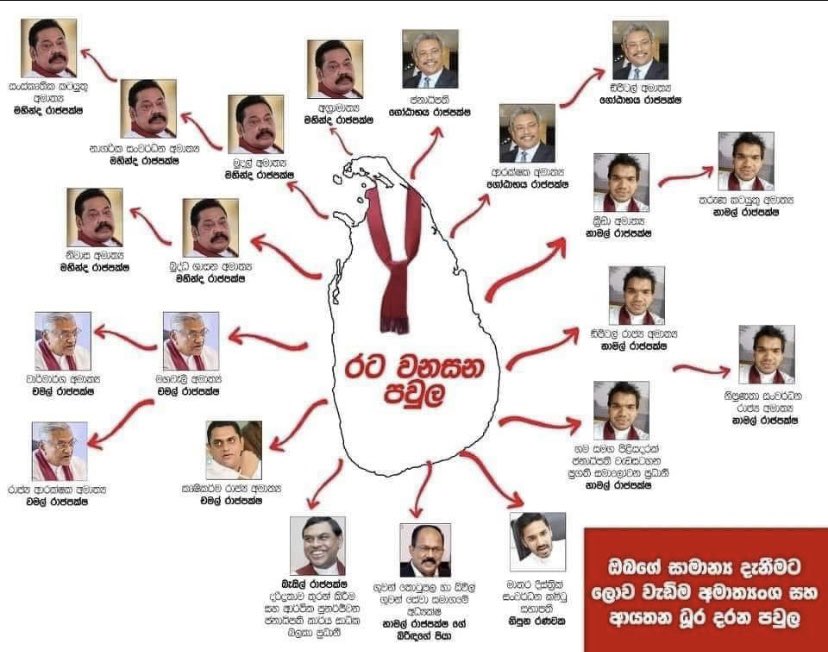

Probably the Rajapaksas’ notion of meritocracy is something of that kind. That fits well with the very structure of the Sri Lankan state, a familiocracy, a rule by the family. Basil Rajapaksa is the ablest of the familial lot and therefore viewed as the fix.

The last hurdle to his parliamentary entry, the ban on dual citizens taking up public office was removed by the government under the 20th Amendment to the Constitution. Even parochial considerations and hysteria over foreign interference that this government whipped up during its election campaign were discarded for the time being for the greater national good so that aggrieved Basil Rajapaksa could return to Parliament with his dual citizenship intact. Much like other similarly personalized characters of the 20th amendment, that was tailor-made to Basil Rajapaksa, who for his part was industrious enough to wait till the dust settled before launching on his re-entry.

According to the government’s MPs and Ministers, ‘the golden age’ of Sri Lankan politics could begin only after Basil Rajapaksa entered Parliament. Sri Lankan voters might wonder, then why the hell they voted for Gotabaya Rajapaksa to the presidency? He even spent his month-long holiday in America formalizing strategies to resurrect the economy, says his nephew Namal Rajapaksa.

Basil Rajapaksa held the same portfolio during the second term of Mahinda Rajapaksa presidency, during which, rumour mill and diplomatic cables whispered of a Mr.10%. Later when his party was out of power, he was investigated over the ownership of a luxury mansion in a 16-acre riverfront land in Malwana. He denied the ownership and the magistrate ordered the auction of the estate. There is no change in that decision, so far.

For a long, the government MPs have urged Basil Rajapaksa to enter Parliament so that the nation can benefit from his economic wizardry.

All that platitude, pleading and scrumble for bed crumbs by the SLPP underlings might give the impression of an illustrious career in Investment Banking and the IMF. However, all that he brings is the Rajapaksa lineage. In a political system, of which defining characteristic is dynastism that count more than any stint in Wall Street.

Meritocracy, loosely defined as a government by those with talent is much desired by many governments, including President Gotabaya Rajapaksa who keeps telling that he appointed senior officials on merit; some indeed are. Equally true is the same institutions keep underperforming even under those men with a proven track record elsewhere. That may explain the constraints of the structure ( in the case of SOEs their organizational structure, philosophy and the relationship with the Government) that limit the efficacy of meritocracy. The same limits apply more drastically in the search for meritocracy in participatory democracy. Voters rarely pick their representatives based on merit. The world’s most famous meritocratic political system, Singapore in reality has choreographed elections in gerrymandered electorates.

If not a brazen hypocrite, a dual national of the US, Basil might have opposed the incorrigible campaign against the Millenium Challenge Cooperation grant, which in the end resulted in Sri Lanka losing the US$ 480m grant.

However, a different kind of meritocracy could also exist in more closed, insular and uncompromising systems elsewhere. For instance, the Chinese Communist Party, which though not open to competition as a freewheeling meritocratic system would augur, still promotes go-getters across a hierarchical structure. That is however a system in which unquestioned loyalty matters more than competency.

Probably the Rajapaksas’ notion of meritocracy is something of that kind. That fits well with the very structure of the Sri Lankan state, a familiocracy, a rule by the family. Basil Rajapaksa is the ablest of the familial lot and therefore viewed as the fix. Blood is thicker than water and the President and PM might also feel it safer with the own sibling running the economy.

Probably Basil Rajapaksa is more commonsensical than his presidential brother. He might have seen the folly of the destructive fertilizer ban, which would impoverish one-fourth of the Sri Lankan workforce. If not a brazen hypocrite, a dual national of the US, Basil might have opposed the incorrigible campaign against the Millenium Challenge Cooperation grant, which in the end resulted in Sri Lanka losing the US$ 480m grant.

He might know the repercussions of not going for an IMF programme before it is too late as investors bet on a sovereign default and the country’s bond issuances have now become a bad joke. Last week, 2/3rd of the US$ 100 million Sri Lanka Development Bonds that were on offer to roll over the govt debt was unsold. Local banks are running short of foreign-currency funding as the forex reserves havereduced to US$ 4.4 billion by the end of April. Trade Minister Bandula Gunawardene says there is little money left for anything else after paying the salaries of the state employees.

However, there are disturbing signs that all the hullaballoo over Basil Rajapaksa’s Parliamentary entry is yet another dynastic venture and much less about saving the economy. Rumours abound about looming changes in the Central Bank to accommodate Ranjith Bandara who is said to be resigning from his national list seat so that Basil Rajapaksa can enter Parliament. When clueless political appointees are at the helm of the already troubled exchequer that would be a big red flag for any investor who has not yet given up.

- Daily Mirror