From the Report of the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief on Sri Lanka.

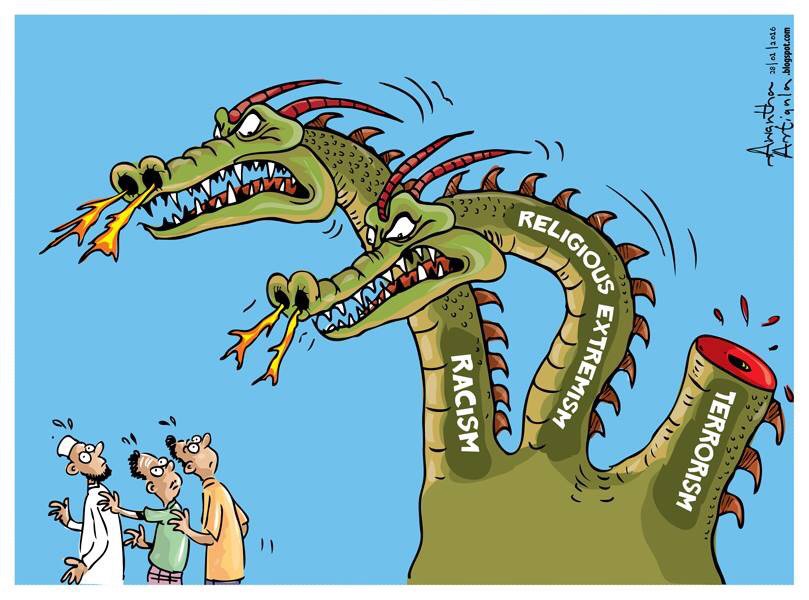

The culture of impunity in Sri Lanka has been repeatedly pointed out as one of the main reasons for which religious extremism and hate speech thrive in the country, undermining the rule of law and human rights. Many complained about how acts of violence are “indulged” by the silence and inaction from the authorities illustrated by some examples discussed above. Some expressed surprise and dismay that large mobs could openly and for several hours rampage through minority community neighbourhoods without hindrance or reaction from law enforcement authorities, or that some of the police participated in those violent incidents or that authorities fail to adequately protect those under attacks even when some of violence continued for several days. In some cases, the attacks took place during curfew hours. These happened during the riots in Kandy district in 2018 and in May 2019 in several locations in the Western and North Western provinces for example.

Some also expressed concern about perceived bias in the way the police addressed complaints. This was particularly the case were the assailants were members of the majority community. Many complained that either police failed to register and investigate complaints raised by them or that they would act in a punitive manner on complaints raised against them while failing to take similar measures when they were the target of attacks, or that generally the police were unsure on how to act in responding to infringements of the law by Buddhist monks. Some blamed politicians for influencing law enforcement citing examples where politicians were allegedly involved in pressuring the police to release persons arrested following violent attacks.

The Rapporteur received reports from the National Christian Evangelical Alliance of about 87 cases of recorded physical attacks at places of worship, residential area, pastors or members of the Evangelical churches (2015-2019); while only 50 cases were reported to the police, and 8 cases went to the courts, there has been not a single conviction of perpetrator even though in some cases, compensation has been granted to the victims. Similarly, the Evangelical Christians communities have documented over 11 cases of incitement to hatred and violence against them, and about 300 instances of harassment or discrimination based on their religious identity. Among those cases that were taken to the police or courts, the result was the same, there was not a single conviction.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses also reported at least 58 cases were referred to the police 2017-2019 of physical assaults, harassments and intimidation, disruption of their worship meetings, vandalism on the places of worship, and refusal of permit for building places of worship. 33 cases have been taken to the court, only 5 cases have been decided in favour of them where perpetrators agreed to stop harassing them but there is still not a single conviction.

Many described problems of double standards in law enforcement depending on which community offends or finds itself targeted by the actions of other. For instance, the Rapporteur heard of cases of violence against minorities perpetrated by the majority community where perpetrators are clearly identified in video recordings but remain unaccountable for years after the incident. Reversely, many complained, that when a complaint is brought forward by members of the Buddhist community, action is swift and, at times, disproportionate and lacks legal impartiality.

The Rapporteur would like to point out that Section 2.4 of SCP’s interim report on Communal and Religious Harmony clearly reported the challenges of the law enforcement, indicating that “[…] The recent incidents of serious violence in Kalutara, Galle, Ampara and Kandy districts have exposed the Police Department’s inexcusable delays to enforce the law and the Attorney-General’s failure in most instances to prosecute the perpetrators of violence.”1

Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights while countering terrorism who visited Sri Lanka in July 2017 in his report2 noted that “the absence of reaction from the Government to incitement to hate speech and racism, and attacks on minorities, including Muslim places of worship, in what is perceived by Tamils and Muslims as ‘Buddhist extremism’, increases the deeply-engrained sense of injustice felt by these minority communities, and increases Tamils’ national sentiments”.

Despite the pledges by the Government to strengthen fundamental freedoms and the rule of the law, it has so far failed to undertake the following critical steps:

• the establishment of a commission for truth, justice and reconciliation as well as a judicial mechanism with a special counsel;

• initiation of a judicial process to look into the accountability for abuses by all sides of the internal conflict;

• the full restoration of land to its rightful civilian owners;

• the cease of military involvement in civilian activities;

• an effective security sector reforms to vet and remove known human rights violators from the military;

• a review of witness and victim protection law including investigators, prosecutors and judges;

• a review and repeal of various legal provisions or legislations, such as the PTA, that are incompatible with international human rights standards;

• domestic law reform to prohibit and try serious human rights violations;

• investigation of hate speech, incitement to violence (including by religious leaders) and any attacks on civil society.

The list above shows that the authorities have not yet demonstrated the capacity or willingness to address impunity for gross violations and abuses of international human rights law and serious violations of international humanitarian law. The State must recognise that without the truth and justice, without the restoration of trust in the people by demilitarizing boundaries and prosecuting perpetrators of the conflict; without the appropriate mechanism and legislation that are compatible with international human rights standards, there will be no reconciliation and peace in the country.

Moreover, Government should not allow the influence of religious clerics to determine public policy in secular matters. On 3 June 2019, a Buddhist monk commenced to fast unto death, demanding the resignation of three Muslim politicians whom he claimed were linked to the Easter Sunday attackers. The leader of the BBS paid him a visit and issued a statement warning of mass mobilisation if the Muslim politicians did not comply with the demand. Large mobs gathered in central Kandy in support of the monk and threatened to get onto the streets to attack Muslims. Without any formal investigation, two Governors had to resign on the same day. Many worry that this incident sets a dangerous precedent of recognising the authority of religious leaders in political matters.

It is essential for the Government to not ignore the simmering tensions and intolerance and the damaging consequences of incitement to hatred and violence in a country that has gone through a long period of internal conflict. Inaction by the authorities could aggravate the simmering tensions and if these were left unattended, Sri Lanka may risk being locked in a vicious cycle of ethno-religious violence. Building societal resilience against violent extremism and incitement to hatred requires a broad-based approach that relies on good governance, rule of law as well as respect for human rights and equality for all. This requires strong political will and strengthened State institutions to tackle the root causes of the religious tensions and intolerance analysed above urgently in order to achieve a sustainable peace and economic growth in the country.

Read the full report as a PDF: Sri Lanka report Religious Freedom by UN SR 28022020