1. Widespread and persistent popular protests in 2022 over the behaviour of top officials reflected a consensus that corruption had paved the way for the economic crisis. The subsequent resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in July 2022 emphasised that addressing the crisis required changes in governance as much as changes in economic policies. The role of civil society in demanding accountability carried an equally important message about the drivers of change.

2. The particular configuration of power under the Presidency of Gotabaya Rajapaksa created unique governance challenges. The excessive concentration of authority in the hands of a group of individuals tightly linked by familial ties served to emphasise the political power of a small elite and perhaps assisted in the coordinated improper use of public power.5 While the Rajapaksa Government lasted less than three years from its start in November 2019, its time in office featured catastrophic declines in tax revenues, the signing of investment agreements negotiated in opaque circumstances granting control over state property and extensive long-lasting concessions, as well as dramatic increases in external and domestic debt.

3. Concerns over the extent policies choices and government practices were driven by private interests were enhanced by the widespread undermining of public accountability and oversight. The passage of the 20th Amendment to the Constitution in 2020, abolishing the 19th Amendment, granted unfettered Presidential control over appointment processes in “independent” bodies such as the Central Bank, the Judiciary, and the Anticorruption Commission while eliminating regulatory bodies in Procurement and Auditing. Oversight bodies in Parliament, including the Parliamentary Accountants Committee and the Committee on Public Enterprises, proved unable to effectively monitor and discipline government actions. At the same time, laws on counter-terrorism were applied in ways that restricted public participation in monitoring and governance.

4. President Wickremesinghe has pledged to confront corruption and change the way the nation is governed. Government reform programs have been announced, including in areas such as fiscal and monetary policy, taxation, public financial management, and anticorruption. Government pronouncements and policy actions have consistently reflected the urgency of making visible progress in the fight against corruption and the appreciation that policy reforms are unlikely to be sustained without structural changes in how the government operates and the mechanisms by which public officials are held to account for their behaviour and performance. President Wickremesinghe has announced that his government is “committed to implementing anti-corruption practices through a government mechanism that emphasises accountability.”

5. The quick passage of the 21st Amendment in September 2022, reimposing limits on the

authority of the President, demonstrated the resolve to unwind the recent attacks on

accountability and the rule of law. Efforts to simply restore past arrangements and institutions are, however, unlikely to be sufficient to address underlying systemic governance challenges and corruption issues that were broadly exposed in the last years.

6. Corruption issues have been at the forefront of the public dialogue on governance for years. The change of governments after the 2015 elections was associated with increasing popular concerns over rising levels of corruption. Notwithstanding, international assessments of governance and corruption, including Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index and the World Justice Project’s Rule of Index, show little alteration in the country’s performance across a range of governance issues. Sri Lanka’s scores from 2016 through 2022 remain relatively unchanged on factors like control of corruption and the rule of law and place it close to average for the region and income

group.

7. A more granular level analysis of corruption reveals a more nuanced story. Results from a detailed survey and interview-based study of corruption conducted in 2019 found a consistent perspective that corruption was pervasive across the country. While slightly more than one-third of respondents had direct experience with corruption, over 85 percent of the interviewed indicated that corruption happened regularly in the hiring of government workers and the awarding of government contracts. Among those who had experienced or witnessed an act of corruption, the encounter happened with a government official in 36 percent of respondents and with a member of Parliament in 35 percent. Grand corruption was perceived to be slightly more frequent than petty corruption – a finding that is quite atypical as citizens’ views on the frequency of corruption are often driven by their own experiences around accessing services (e.g., health care) or in the enforcement of law (e.g., traffic violations) and not related to the actions of higher-level bureaucrats. The incidence of corruption was understood to be similar for politicians and bureaucrats, a finding echoed by similarities in the perceived levels of corruption among ministers and parliamentarians.9 At the same time, until prompted, respondents did not view corruption as a critical problem, seemingly having accepted it as a regular part of governance in the country.

8. Perceptions of the pervasiveness of grand corruption in Sri Lanka may be influenced by extensively reported transgressions involving high-level officials and economic elites. Governmental reviews and investigations regarding specific cases, including Sri Lankan Airlines’ interactions with Airbus, the decision to sharply reduce the import tax on sugar in 2020, and the events around the issuing of bonds in February 2015, produced extensive public information on incidents involving high-level officials. While each of these examples differs in important aspects, they share common features in that they involve multiple state entities, including the Central Bank, that generated extensive profits for private parties while simultaneously saddling the state with costly debts. While each case is distinct, in all instances, high-level officials escaped sanctioning for corruption, including in foreign jurisdictions in one case.

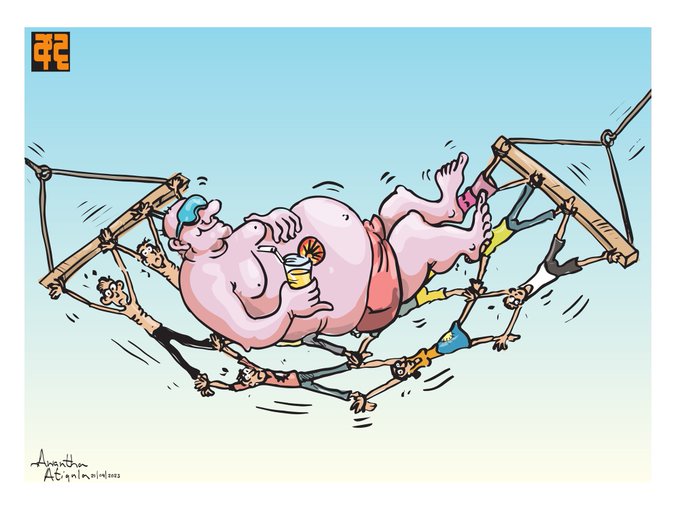

9. Other data provides complementary indications of the prevalence of corruption

consistent with perceptions and the information reported about high-level scandals. For example, a comparison of construction costs in Sri Lanka determined that highway construction costs per kilometre were three times global averages. The explosion of domestic and external debt since 2005 has also closely tracked actions that have restricted the independence and competency of key institutions, increased the concentration of authority among closely connected individuals, and committed the state to financing mega-projects approved at the Cabinet level using opaque processes.

10. A set of common elements can be identified within the information available on the severity of corruption in Sri Lanka. High-value corruption issues appear strongly associated with state-owned enterprises and highlight the close relationships between public institutions and private firms, including in the financial sector. Multiple avenues exist by which officials influence and direct the actions of public and private parties, often in ways that lack transparency. High levels of discretion in the creation and implementation of policies, including in areas like public procurement, state contracting, and the granting of concessions for strategic investments, have contributed to corruption vulnerabilities, especially as state actions in these areas cannot be easily challenged. Opaque control

over public activity is assisted by high-levels of organization fragmentation of authority, combined with extensive concentration of responsibility in the hands of a limited number of individuals, such as the practice of having the President of the nation also serve as Minister of Finance. Corruption appears to be less about actions around specific transactions and more about long-established relationships that bind together public and private elites.

11. Overall, current arrangements act to insulate top government officials from accountability. Government control over key enterprises limits the ability of market forces to discipline government policies and rent-seeking behaviour. Extensive government regulation in core sectors, such as agriculture, electricity, and construction, restricts market-based accountability and generates extensive opportunities for top officials to direct state resources to privileged private parties. Internal sources of accountability, such as regulatory bodies, inspectorates or internal audit functions, lack capacity and authority and are regularly circumvented by a high-degree of discretion afforded to high-level officials, and by extensive mechanisms for exerting informal influence on decision-making

and the application of regulations. Government decisions relating to capital investments, high-value procurement, the granting of concessions for “strategic” investments, the marketing and payment of debt instruments, or the divestiture of state property occur through opaque processes at the highest level of government with limited oversight and contestation. External mechanisms of accountability, such as auditing and parliamentary oversight, have proven to be ineffectual in constraining questionable behaviour, in part due to the absence of effective follow-up mechanisms for actions that waste public resources. The absence of functional relationships with external law enforcement agencies enables officials to enjoy the profits of their illicit actions outside the country.

12. Governance and corruption issues have imperilled national and social well-being. The recent past has demonstrated the extent of impunity afforded top officials, even for ruinous behaviour. At the same time, civil society has proven its ability to organise and demand accountability as a last resort. Confronting corruption in Sri Lanka effectively requires short-term actions to address core vulnerabilities combined with more long-term actions to introduce structural changes in governance and accountability that address the underlying governance weaknesses. Dismantling current protections that afford officials immunity for their actions is fundamental to achieving and sustaining success.

Read the full report with foot notes: IMF report – Governance Diagnostic Assessment -Sep 23 1LKAEA2023002 (1)