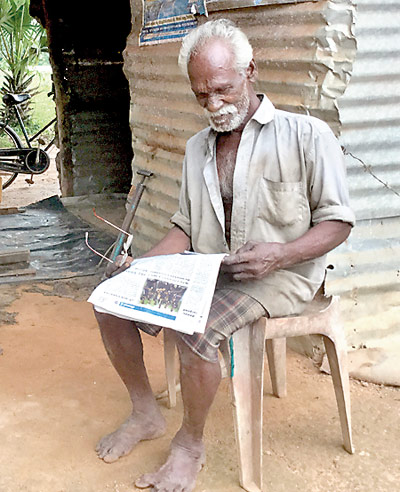

Three years after Thiruchelvan Ketheeswaran arrived in Keppapilavu village in Mullaitivu to start a new life for his family, his hopes are crumbling.

Ketheeswaran was among the thousands of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) resettled in a brand-new village as the final phase of the government’s resettlement process concluded. He could not return to his own land, 1-2km away.

Born and raised in a farming family, he works now as a mason because his acres of paddy lands have been acquired by the military following the end of the bloody war in 2009.

A father of two children, he finds it difficult to support his family. “With the start of the monsoon season we have no jobs in the village and there is no-one to employ us since most of us are living under the poverty line. I have to go other villages in search of jobs,” he said.

The so-called Keppapilavu “model village” project created in 2012 was a brainchild of the military and was facilitated by the Resettlement Ministry.

It comprises three villages – the Pilakaadhu, Sooriyapuram, and Keppapilavu Grama Sevaka divisions. At least 300 families’ lands were taken by the Defence Ministry and these people were resettled in plots of state lands as a temporary step.

The isolated village is located in the Mullaitivu district, some 20km away from the main town.

The military and the Resettlement Ministry built 24×10-foot houses for all the families in the village. The internal roads and mini-bridges are being built by the military as permanent structures.

“What we need is the return of our land. If they give back our land we don’t have to depend on the military or any authorities for our survival.

We’re grateful for what they have done in the past but we don’t want to see them involved in our day-to-day lives,” Ketheeswaran said.

The Government Agent (GA) of Mullaitivu, Roobawathy Ketheeswaran, said it was very unlikely that these villagers would go back to their own lands.

“We have decided to give them more state lands for farming activities in the Maligai Theevu area in lieu of their lands acquired by the military,” she said.

Rejecting the allegation that the military is involved in the residents’ civil activities, she said the military was being used to provide manpower in construction work only. “Their labour cost is very low.

That’s why we are using them,” she said.The head of Keppapilavu’s Rural Development Society, Rasaiah Parameswaran, says the government had no intention of releasing the acres of paddy lands commandeered for the sake of national security and is trying to resettle the IDPs permanently in the model village.

“We took up these matters with the government authorities and the politicians who claimed to be representing us but so far there has been no positive reply from them. The last time they visited us was during the presidential election in January,” he said.

During the visit of the UN Working Group on Enforced Disappearances to the country in November, the military put up a new village signboard omitting the words “model village”.

Mr. Parameswaran is alarmed by this move and suspects that the villagers have been portrayed as permanent residents.

The model village has seen the rise of many social problems.

Last month, two teenagers allegedly involved in separate crimes of sexual abuse were sent to a children’s disciplinary home.

Caste issues are a curse for the community. Different groups – farmers, fishermen and a mix of lower-caste groups live together in the “model village”, which was divided into equal plots for every family.

The fisherfolk and others from oppressed groups feel that they have been marginalised by one group in everything from constructing a well to distribution of lands.

Students rarely turn up for class at the Keppapilavu Primary School. The Principal, S. Uthayashankar, said poor attendance was due to the parents’ lack of education and to poverty, which plays a big role in whether a child is sent to school.

None of the students in Grade 5 passed the scholarship exam held this year.

“We tried awareness programs for the parents but their priority is for the child to grow old enough to make a living for the family.

Only a handful of students go up to the GCE Ordinary Level in the nearby secondary school,” Mr. Uthayashankar said.

The families headed by women are the most vulnerable: poverty hits them hard.

In Keppapilavu there are 60 families in which the female is the breadwinner and they are struggling to make a living in the absence of employment opportunities or alternative income sources.

Most of the women have to travel out of the village in search of work and this creates family problems, according to the Vice President of the local Women’s Development Co-operative, Sivan Sangeetha.

“When they are out there is no one else to look after the family – some families break up,” she said, pointing to a recent incident when a father of two eloped with a girl from the next village.

She said most of the families own lands and coconut estates now under military control and if they regained their property their lives would change.

Muttaiah Alagi, who lost her husband in the final phase of the war, has to take care of herself and also her widowed daughter and grandchildren.

She makes about Rs. 300 a day picking cashew nuts during the season and at other times seeks work as a labourer.

“I have two acres of coconut estate as my dowry – now it is in the military-controlled area. If I could have access to it I wouldn’t have to go to outsiders to look for jobs,” she said.

Rasan Selvam, a bicycle mechanic in the village, said most people never pay him in cash for the repairs he carries out. “I know almost everyone in the village is going through difficult times but they also should know I have to support my five-member family too,” he said.

He says he doesn’t know any work other than bicycle repahttps://srilankabrief.org/wp-admin/post-new.phpir even though others who have not been able to find sustainable work have turned their hands to other occupations.

“This feels like living in a refugee camp, no better than Menik Farm where we were detained earlier. I just want to go to my own land and would like to die there because that is my home,” Rasan said.

The military spokesman, Brigadier Jayanath Jayaweera, said the Mullaitivu security forces commander was not immediately available to respond to the issues raised by the villagers and would provide information later.