by Garvin Karunaratne.

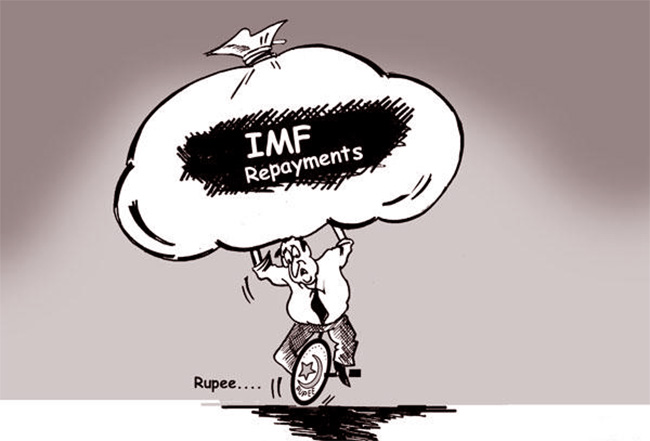

The Sri Lankan government is finding it hard to fulfil the regulations agreed upon with the IMF in the Houses of Parliament on April 28, 2023. However, there was no other option but to agree. According to Professor Vasanta Atukorale, the increases in taxes amount to a staggering 441%. The IMF’s experts fail to understand that implementing these regulations will cause untold hardships to the public and may even lead to a severe recession. Perhaps, this is the ulterior motive of the IMF.

Sri Lanka was not a dollar in foreign debt in 1977. From 1948 to 1977, the country made strides in development, opening up land, colonisation schemes for people, building tanks, developing agriculture and industries, and implementing welfare measures. The country became self-sufficient in paddy production, its staple crop, and produced all its textiles. This development effort involved agricultural marketing, agricultural extension, small industry, and district administration. The golden era of Premier Dudley Senanayake’s rule, lasting 29 years, was where the people enjoyed freedom and development.

1977 – JR and IMF

The IMF abolished many development programmes in 1978. The problem began with the Structural Adjustment Programme imposed on Sri Lanka by the IMF when President J. R. Jayewardene sought assistance from the IMF, which gave loans freely on condition that Sri Lanka follow neoliberal economics and allowed the rich to spend foreign funds that the country had obtained as loans. This led to foreign debt. Worse still, President Jayewardene and his Minister of Finance Ronnie de Mel were made to believe that this path would lead to development.

In 1978, the IMF even gave grace periods, when Sri Lanka did not need to pay the interest and repayment instalments on loans so that the leaders would not be burdened with the repayment. The burden was shifted to future leaders.

IMF also responsible for Sri Lanka crisis

Many specialists have proposed alternative ways of dealing with the current crisis. The World Bank Country Director Fariz Hadad Zerous has said that the current crisis is not a temporary liquidity shock but the result of longstanding structural weaknesses, poor governance, and a public debt that is unsustainable. However, the World Bank Country Director needs to be told that it was the IMF itself that is to blame for taking Sri Lanka on this path of living on loans.

From Independence in 1948 to 1977, Sri Lanka’s development was done through various development programmes that involved people in production aimed at self-reliance. The IMF abolished all the developmental departmental activities and confined the administrators to the barracks while coming up with the ludicrous basis that the private sector was to be the engine of growth. It was this decision of the IMF imposed in 1978 that crippled the development of the country. The private sector has self-aggrandizement as its aim. The development of the country is not their concern.

T. B. Illangaratne time

Until 1977, the country had import restrictions in place to ensure that it could manage with its earnings. The development of the country was entirely run with local currency – the rupee – collected by taxes supplemented by money printing, while the foreign exchange that came in through exports and services was precisely collected and used for the purchase of importing essentials. Very small allocations were made for imports. The total expenditure of Sri Lanka in 1961/62 was Rupees 2013 million, all local rupees. The 1963 Budget Speech of Minister T. B. Illangaratne tells how imports of textiles were reduced by a third, powerlooms were imported, but imports of cars were banned.

The Budget Speech outlines the strategy to manage imports within the available expenditure, highlighting its potential as a developmental exercise. Minister Illangaratne said, “We stopped the import of coffee to increase coffee production” (p.1237). I met Minister Illangaratne in 1971, when I needed his approval for foreign exchange allocation to import dyes for my Crayon Factory in Morawaka. The Ministry of Industries refused to provide us with an import allocation because we were a cooperative. However, I learned that the Controller of Imports was about to allow an allocation of foreign exchange for the import of crayons. So, I intervened and convinced the Import Controller that by giving our Crayon Factory a foreign exchange allocation for the import of dyes, he could cancel all imports. I needed Minister Illangaratne’s approval as this procedure had never been done before. When I showed him the crayons we produced, I remember the gleam on his face. He insisted that I establish a Crayon Factory in Kolonnawa, his electorate, and ordered the total cancellation of all imports on crayons. That is how statesmen served the national interest.

Foreign aid could go either way

Today’s economic meltdown, with foreign debt amounting to $56 billion, did not come without warning. In 1990, I began a series of lectures on Third World Studies at the Westminster Adult Education Institute, where I discussed how Sri Lanka’s foreign debt was increasing. By 1989, the foreign debt had increased to $5 billion. In 1992, the South Asian Forum of the University of London invited me to speak on Sri Lanka, and I commented that foreign aid could serve as an engine of growth if handled prudently. However, foreign aid could lead to chronic debt, poverty, high unemployment, and even uprisings if accepted in a non-developmental manner. I also mentioned that the healthy balance of payments achieved during the period of 1970-1976 turned into a nightmare of adverse deficits due to the governments that came into power since 1977 (From How the IMF Ruined Sri Lanka & Alternative Programmes of Success, Godage, 2006).

The foreign debt ballooned to $9.5 billion by the end of the UNP rule, $11.5 billion by 2005, $42.9 billion at the end of 2014, and $56 billion by 2019. Initially, the IMF gave loans, but it later backed out, and the country had to raise funds through other sources on less attractive terms. International sovereign bonds were obtained at high interest, as much as $4 billion during the Rajapaksa Regime of 2008-2015 and $10 billion ISB loans during 2015-2019. It is important to note that President Gotabhaya did not create the foreign debt. However, he made wrong decisions, such as providing a massive tax break to large enterprises and his infamous agricultural extension programme of using compost and banning the use of inorganic fertilisers, which led to massive crop failure. It is difficult to imagine a successful military commander failing to act forcefully in the interests of the country, but it did happen. The cause of Sri Lanka’s total economic meltdown lies in the salient features of the Structural Adjustment Programme imposed on Sri Lanka since the end of 1977. We have not used the loans for any purpose in development but lived extravagantly on loans, as dictated by the IMF. Corruption and politics in decision-making also aggravated distress, but the salient factor is that Sri Lanka started living on loans and abandoned development programmes. The IMF even disbanded the Planning Department and confined all development workers to the barracks.

2023 IMF loan – No measures to increase the productivity

It is unfortunate to note that the IMF’s $3 billion loan provisions for Sri Lanka do not include any measures to increase the country’s productivity and boost people’s incomes. The IMF’s focus is primarily on increasing the tax base, restoring price stability, restructuring debt, rebuilding reserves, and enabling the country to purchase essential goods from abroad in order to put it on a growth path. The Central Bank is expected to purchase foreign exchange worth $1.4 billion to rebuild reserves. According to the Financial Times, the reforms also involve addressing corruption and inefficiency at state-owned enterprises, combating inflation, recapitalising the banking sector, and overhauling the tax system, which currently sees half of the country’s taxpayers paying less than 5% of their income to the state.

However, the IMF seems to overlook the fact that taxes are collected in local currency and do not have any direct impact on the repayment of foreign debts. Therefore, Sri Lanka’s only viable option is to implement import substitution programmes that will reduce the country’s dependence on imports and simultaneously generate incomes for the people. The IMF has not prohibited such productivity-enhancing measures, and it is up to Sri Lanka’s leaders to devise programmes that can increase production.

Sri Lanka has previous experience with successful development programmes such as the Divisional Development Councils Program (DDCP) implemented by the government from 1970-1977. The DDCP provided employment training to 33,200 youths, established agricultural farms, and set up small industries. Many Districts also established small agricultural farms and industries, such as the Mechanised Boatyard at Matara, which produced 35 seaworthy fishing inboard motor boats a year and a Cooperative Crayon Factory, which had country-wide sales. These were established in a short period, within two to three and a half months, respectively.

Employment creation programmes that can also boost production have proven successful, such as the Youth Self Employment Programme established by the author in Bangladesh, which has created three million entrepreneurs and is now recognised as the world’s most successful employment creation programme.

It is worth noting that since Sri Lanka started following the IMF’s policies in 1977, no new development programmes have been implemented to reduce poverty, develop the country’s resources, or train people to make what is imported. The author highlights the work of previous statesmen in implementing successful development programmes, which can serve as a model for current leaders.

In conclusion, it is crucial for Sri Lanka’s leaders to establish programmes that will produce what is currently imported and create incomes for the people while simultaneously reducing the country’s foreign exchange expenditure on imports.

(Dr. Karunaratne is a former Government Agent and Commonwealth Fund Advisor to the Ministry of Labour and Manpower, Bangladesh 1981-1983.)

The Island/03.05.2023