DRI.

The Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) of the European Union (EU) is a trade arrangement that allows developing countries to pay less or no duties on their exports to the EU. The EU offers GSP programmes to help vulnerable countries to reduce poverty, improve governance and foster a process of sustainable development.

The Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+) is a special component of the GSP scheme that provides additional trade incentives to developing countries already benefitting from GSP. The EU introduced GSP+ with the aim of providing more extensive market access than the standard GSP scheme, giving beneficiary countries duty free access to EU markets for over 7200 products.

In return for these incentives, the recipient countries must ratify and effectively implement core international conventions in the fields of human rights, labour rights, the environment and good governance. Revised in 2014, GSP+ now incorporates strict monitoring mechanisms and a role for civil society in that process. The addition of non-state actors as observers in the scheme renders the monitoring mechanisms more transparent and objective.

CONDITIONS OF GSP+

The country must be “vulnerable”, meaning that the World Bank has not classified it as a high-income or upper-middle income country during three consecutive years (in other words, it is a beneficiary of the standard GSP).

Its imports into the EU must be heavily concentrated in a few (the seven largest sections of its GSP-covered imports to the EU must represent more than 75% of the value of its total GSP-covered imports). It must also have a low level of imports into the EU (its GSP-covered imports into the EU must represent less than 2% of the value of the EU’s total GSP-covered imports from all beneficiaries).

The country must ratify and effectively implement 27 international conventions on human and labour rights, environmental protection, and good governance without any reservations that are prohibited by those conventions, or which are incompatible with the object and purpose of the conventions.

The country must comply with the monitoring procedures and requirements imposed by those conventions, as well as with the EU’s monitoring procedure on GSP+ led by the European Commissions.

MONITORING PROCESS

After a country becomes a GSP+ beneficiary, it is subject to a monitoring process that repeatedly takes place over two-year cycles. The process involves two interrelated tools: the scorecard and an ongoing dialogue with the beneficiary authorities.

The scorecard

The “scorecard” is an exchange of information on the shortcomings related to each of the 27 conventions, as identified by the international monitoring bodies.

When a beneficiary country joins GSP+, the Commission compiles an assessment of the beneficiary’s compliance with GSP+ commitments (the 1st “scorecard”).

The lists of issues in the scorecard are updated annually, and reflect 1) the progress made in the effective implementation of the conventions and 2) serious efforts made by the country to tackle the identified shortcomings leading to the GSP+ dialogue.

The GSP Dialogue

The “dialogue” describes the close engagement between the EU and the beneficiary countries, based on mutual trust and cooperation,to tackle shortcomings as well as discuss difficulties and achieved progress. The dialogue makes use of a wide range of sources beyond the monitoring bodies of the international conventions, such as civil society, local or regional government authorities, trade, as well as human rights and labour rights organisations. The dialogue results in the enhancement of the constructive role of local actors in assisting local, regional and central authorities to meet their commitments.

SRI LANKA: GAINING AND LOSING GSP+

Sri Lanka has been a beneficiary of the EU’s standard GSP since the scheme’s inception, and it began to benefit from GSP+ on 15 July 2005. However, on 15 August 2010, the EU suspended Sri Lanka’s GSP+ status. The EU’s decision to withdraw GSP+ benefits from Sri Lanka was based on the findings of a Commission investigation that identified shortcomings in the implementation of three UN human rights conventions: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention Against Torture (CAT), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).3

EFFECTS OF GSP+ ON SRI LANKA’S ECONOMY

Despite the short duration during which Sri Lanka participated in GSP+, recent analyses of the scheme’s participant countries have identified Sri Lanka as one of the greatest beneficiaries of GSP+.4 Indeed, the large economic impacts of GSP+ on Sri Lanka were immediately manifest. Within the first year of Sri Lanka gaining GSP+ status, the EU replaced the North American market region (NAFTA) as the country’s largest export market.5 The growing strength of its ties with EU markets proved crucial for Sri Lanka during the financial crisis and the consequent contraction of the US market. While Sri Lanka recorded some losses due to the US crisis, its economy remained resilient.

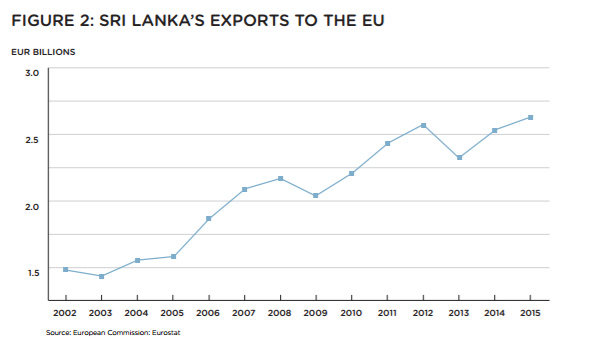

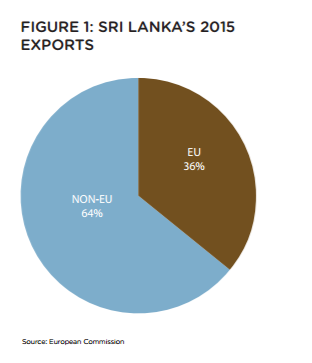

Since the loss of GSP+, Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU have continued to grow (see Figure 2), but the rate of growth has declined (see Figure 3). During Sri Lanka’s participation in GSP+, the share of its exports to the EU region increased progressively from 28% to 39%. The value of Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU increased from USD 1.8 billion in 2004 (the year before the introduction of GSP+) to USD 2.9 billion in 2009 (the year before GSP+ was suspended).6

Sri Lanka’s average annual growth of exports to the EU before GSP (2001-2004) was 11.5%.7. It rose to 16.4% in the GSP+ period (2005-2009). Since the loss of GSP+, this figure has again declined, sitting at 7.4% during the period 2010 to 2014 (see Figure 3).

Before Sri Lanka received GSP+ status, it already enjoyed preferential tariff rates on the majority of its exports to the EU under the standard GSP. However, while the standard GSP programme offers Sri Lanka reduced tariff rates on a wide range of products, GSP+ entirely removes tariffs on many of these products, providing more extensive coverage (including on sensitive items) and preferential margins.8

Between 2008 and 2010, for example, approximately 29% of the total value of Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU were subject to the same tariff rates under the standard GSP and GSP+ schemes; however, for approximately half of Sri Lanka’s total exports in this period, a difference of between 5% and 10% existed between the two schemes.9

With the significant difference in tariff rates, Sri Lanka’s use of the trade preferences grew significantly after the introduction of GSP+. The usage rate increased from 42% in 2003 to 72% in 2008.10 Since the 2010 withdrawal of GSP+, the use of tariff preferences has again declined.11 Some analysts have attributed the low use under GSP to its challenging rules of origin.12 That is, due to the high costs that the rules of origin add to the production of exports, many Sri Lankan businesses calculate that the benefits of GSP are outweighed by the

costs of complying with these requirements.

EFFECTS OF GSP+ ON SRI LANKA’S APPAREL EXPORTS

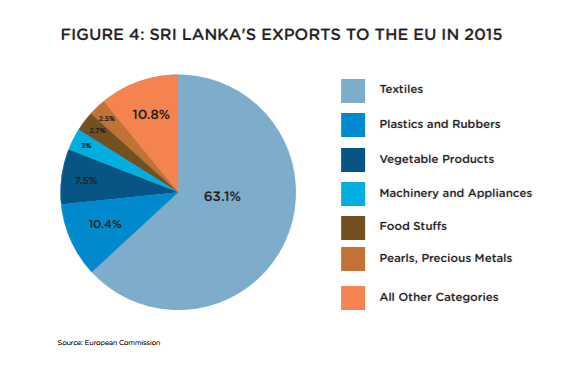

GSP+ status had the greatest impact on Sri Lanka’s apparel exports, which account for approximately 60% of the country’s exports to EU markets and almost 40% of Sri Lanka’s total exports (see Figure 4).13 Due in large part of the effects of GSP+, the EU, according to the Institute of Policy Studies, became the largest market for Sri Lanka’s apparel imports starting in 2008.14

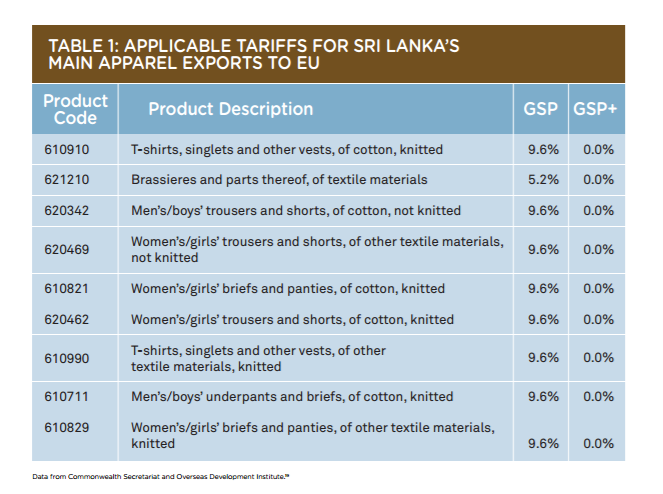

GSP+ resulted in significant benefits for apparel exports due to the significant contrast between its tariff rates and those of standard GSP. Tariff rates on apparel under GSP range between 5.9% and 9.6% (see Table 1). With 0% tariff rates on all apparel categories under GSP+, the difference in categories of apparel is equal to the amount of the GSP tariff rate. Moreover, the 9.6% difference that applies to many apparel sector exports is the second largest percentage point difference between the two schemes (second only to non-motorised vehicle,

which has a 10.5% difference).

With these lowered rates, the tariff preferences on apparel enjoyed much higher use under GSP+. The use of apparel tariff preferences for the period 2005-2010 for both HS 61 and 62 (key garment categories) peaked at 77% and 55% respectively in 2009 (the last full year GSP+ preferences were available). Before GSP+, these rates were significantly lower, averaging between 35% and 15% respectively for HS 61 and 62 in the period 2002-2004.15 With the suspension of GSP+ and the return of tariffs to the standard GSP rates, the use of apparel trade preferences has again declined.

Since the loss of GSP+, Sri Lanka’s apparel exports have also faced strong competition from countries that maintained – or recently gained – access to tariff concessions in the EU, including the remaining beneficiaries of the GSP+ scheme. The adverse effects of Sri Lanka’s exclusion from GSP+ increased as a result of the 2014 reforms, which offer beneficiaries additional advantages, such as the removal of product graduation.16 In a recent report by Ashani Abayasekara, a number of interviewed stakeholders in the Sri Lankan apparel industry noted that the GSP+ concessions had been crucial for their ability to keep up with competitors who benefit from tariff concessions.17

All together, the suspension of GSP+ has yielded very negative implications for Sri Lanka’s garment industry, resulting in heavy financial losses, the closing of 25 garment factories in the three years after the suspension and the loss of thousands of jobs.18

REGAINING AND MAINTAINING GSP+

The EU Ambassador to Sri Lanka has recently expressed optimism about Sri Lanka’s re-entry to the GSP+ scheme; his optimism stems from the fact that the country has made a “degree of progress” towards fulfilling the conditions of GSP+ over the course of the past year.20 These advancements are crucial, as the EU does not require that all issues related to the implementation of the required conventions are addressed before GSP+ is granted, but only that the country demonstrates commitment to achieving this result as well as continuous progress towards it.21 The Ambassador has been clear that GSP+ will not simply be reapplied because of the election of a new government; GSP+ will only be

granted based on “objective reasons” related to Sri Lanka’s progress towards fulfilling the scheme’s requirements.22 The EU revised these requirements in 2014, making them stricter than when Sri Lanka was first a participant of GSP+.

REVISED CONDITIONS OF GSP+23

1. Monitoring has been enhanced by means of the European Commission’s continuous dialogue with beneficiary countries, and by mandating reports every 2 instead of every 3 years. Scrutiny is now carried out not only by the Council of the EU, but also by the European Parliament.

2. Beneficiary countries need to fully cooperate with the international monitoring bodies, without reservations, including as regards to their reporting obligations.

3.Withdrawal mechanisms are more objective. To complement the reports of the international monitoring bodies, the EU may use other sources of accurate information. Also, the burden of proof has been reversed: when evidence points to problems with implementation, it is up to the beneficiary country to demonstrate a positive record.

ROLE OF STAKEHOLDERS IN GSP+

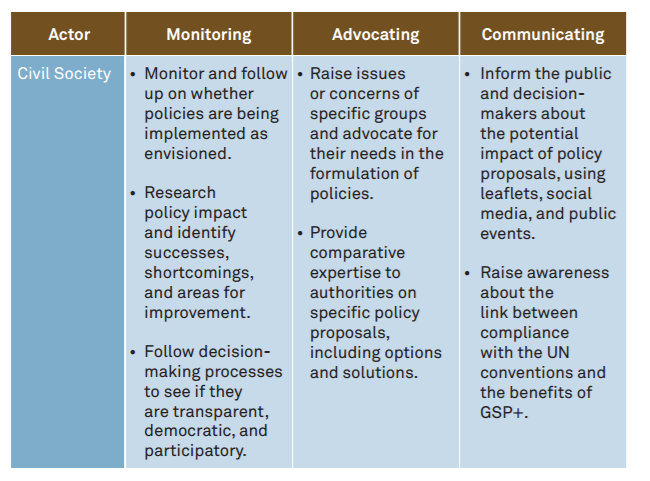

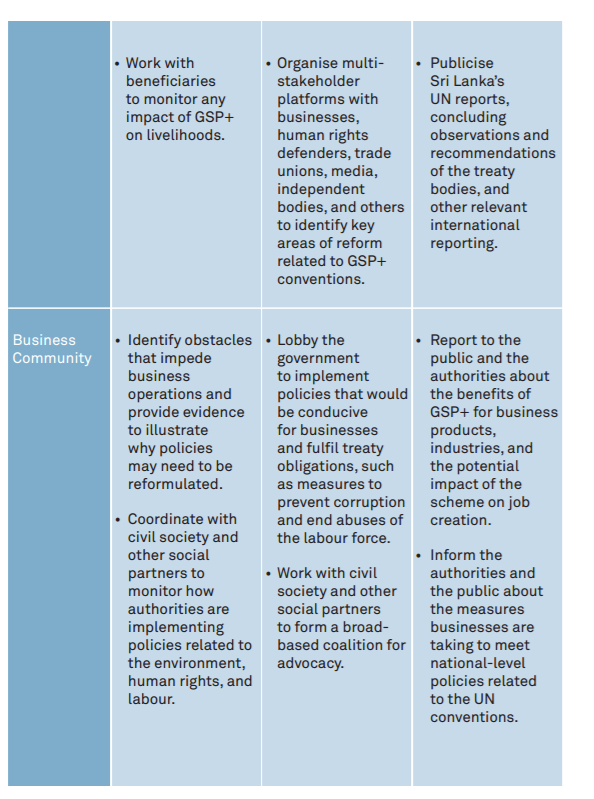

As a result of the revised conditions of GSP+, civil society, the business community, and other local stakeholders can now play an essential role as “third party” sources for the European Commission’s biannual reports. These diverse stakeholders can contribute to the GSP+ process by 1) monitoring how state authorities fulfil treaty obligations, 2) advocating for improvements and 3) acting as interlocutors to communicate the views of the Sri Lankan public.

Civil society and businesses can play constructive roles by assisting the Sri Lankan authorities in key areas of policy implementation and reform. The importance of this role has been demonstrated by the experiences of other GSP+ beneficiary countries. For example, government authorities in Armenia engaged civil society in the implementation and monitoring of the National Strategy on Human Rights Protection 2014-2016, and worked with the business community on specific actions to prevent corruption in line with Armenia’s commitments under the UN Convention Against Corruption.24

Civil society and businesses can play constructive roles by assisting the Sri Lankan authorities in key areas of policy implementation and reform. The importance of this role has been demonstrated by the experiences of other GSP+ beneficiary countries. For example, government authorities in Armenia engaged civil society in the implementation and monitoring of the National Strategy on Human Rights Protection 2014-2016, and worked with the business community on specific actions to prevent corruption in line with Armenia’s commitments under the UN Convention Against Corruption.24

Similarly, the Georgian authorities are now preparing the 2016-2017 human rights action plan in close cooperation with civil society.25 In Pakistan, moreover, civil society organisations and representatives of the business community have recently begun to participate in multi-party dialogues with the government (facilitated by DRI) to discuss GSP+ and its conditions in order to identify priority human rights reforms to jointly take forward.26

As a primary beneficiary of the GSP+ status, the business community has a vested interest in helping Sri Lanka to achieve the scheme’s conditions. In addition to 1) ensuring compliance with labour standards at factories and job sites as well as 2) contributing to the improved protection of human rights in the country through corporate social responsibility, the Sri Lankan business community can also 3) work with the government to push for enhanced protections of human rights.

The Sri Lankan business community already played an important advocacy role in 2010 when the EU set conditions on Sri Lanka’s maintenance of GSP+, and the EU has recently called on Sri Lankan businesses to push the government once again for enhanced rights protections in order to speed up the process of reinstating GSP+.27 The business community could, for example, reinitiate dialogue over the implementation of national labour policy and amendments, or work with the Sri Lankan authorities to promote collective bargaining in workplaces; both of these actions would address salient issues covered by the current conventions of the International Labour Organisation.28

REFERENCES

1 European Commission, “The EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP),” April 2014. <http://www.sice.oas. org/TPD/GSP/Sources/EU_GSP_04_2014_e.pdf>

2 European Commission, “Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP),” 30 December, 2013. <http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1006>

3 The investigation of the Commission identified shortcomings in the legal and institutional framework for the implementation of the conventions, weaknesses in the independent commissions and human rights institutions,and widespread unlawful restrictions on civil and political rights. See Commission of the European Communities.

“Report on the Findings of the Investigation with Respect to the Effective Implementation of Certain Human Rights Conventions in Sri Lanka,” 2009. <http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2009/october/tradoc_145152.

pdf>

4 See e.g., Bonapas Onguglo, “EU GSP Scheme Is a Key Tool for Increasing Trade of Developing Countries, Especially in the Context of the Global Economic Crisis.” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2010. <http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2010/march/tradoc_145917.pdf>

5 D.T. Kingsley Bernard, “The Withdrawal of EU GSP+ Scheme: Its Impact on Sri Lankan Exports and Economy – Are We Ready to Cushion the Economic Shock?” The Island, 22 August 2010. <http://www.island.lk/index. php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=4997>

6 Suwendrani Jayaratne, “Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP+) and Its Impacts on the Sri Lankan Economy,” Economic Review (June-July 2009). <http://dl.nsf.ac.lk/bitstream/handle/1/14234/ER-35%283-4%29-

70.pdf?sequence=2>

7 Felix A. Fernando, “The Difficulties Faced by an Apparel Manufacturer after GSP Plus Was Withdrawn,” Seminar on GSP+, European Chamber of Commerce of Sri Lanka (ECCSL) – “Can Sri Lanka Regain GSP Plus?”, 23 March 2015.

8 Matthew Snyder, “GSP and Development: Increasing the Effectiveness of non-Reciprocal Preferences,” Michigan Journal of International Law Vol. 33, No. 4 (2012).

9 Commonwealth Secretariat and Overseas Development Institute, “Changes in the European Union’s Generalized System of Preference Regime: The Implications for Sri Lanka,” Draft Report. London: Overseas Development Institute, 2012, as cited in Ashani Abayasekara, “GSP+ Removal and the Apparel Industry in Sri Lanka: Implications and Way Forward, South Asia Economic Journal Vol 14, No. 2 (2013). <http://sae.sagepub.com/

content/14/2/293.abstract>

10 Deshal De Mel, Suwendrani Jayaratne and Dharshani Premaratne, “Utilization of Trade Agreements in Sri Lanka: Perceptions of Exporters vs. Statistical Measurements,” Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper Series, No. 96, March 2011. <http://www.unescap.org/resources/utilization-tradeagreements-sri-lanka-perceptions-exporters-vs-statistical-measurements>.

Also see Janaka Wijayasiri, “Utilization of Preferential Trade Arrangements: Sri Lanka’s Experience with the EU and US GSP Schemes,” Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper Series, No. 29, January 2007. <http://www.

unescap.org/sites/default/files/AWP%20No.%2029.pdf>

11 Abayasekara, “GSP+ Removal and the Apparel Industry.” 12 José Anson and Marc Bacchetta, “Non-Reciprocal Preferences for LDCs in Textile and Clothing,” 2005 as

cited in Patrick Low, Roberta Piermartini and Jurgen Richtering, “Multilateral Solutions to the Erosion of NonReciprocal Preferences in NAMA,” World Trade Organization, 16 May 2008. <http://siteresources.worldbank.org/

INTTRADERESEARCH/Resources/544824-1235150721870/ch07_Low_Piermartini_Richtering_Multilateral_Solutions_to_Erosion_Pref_NAMA.pdf>

13 Sri Lanka Export Development Board, “Disaggregated Export Performance 2005-2014.” <http://stat.

srilankabusiness.com/epi2015/pdf/Pg%28014-019%29-%20Dissag.%20Export%20Performance%202005%20-%202014.pdf>; and Delegation of the European Union to Sri Lanka and the Maldives, “Trade.” <http://eeas.

europa.eu/delegations/sri_lanka/eu_sri_lanka/trade_relation/index_en.htm>

14 Institute of Policy Studies, “Sri Lanka: State of Economy 2008,” 2008. <http://www.ips.lk/publications/state_of_economy_report.html>

15 Abayasekara, “GSP+ Removal and the Apparel Industry in Sri Lanka.”

16 Commonwealth Secretariat and Overseas Development Institute, “Changes in the European Union’s Generalized System of Preference Regime.”

17 Abayasekara, “GSP+ Removal and the Apparel Industry in Sri Lanka.”

18 Ashwin Hemmathagama, Major Losses in Apparel Sector from Loss of GSP Plus: Govt.,” Daily FT, 24 October 2013. <http://www.ft.lk/2013/10/24/major-losses-in-apparel-sector-from-loss-of-gsp-plus-govt/>

19 Commonwealth Secretariat and Overseas Development Institute “Changes in the European Union’s Generalized System of Preference Regime.”

20 “Lanka to Regain GSP+ – Daly,” Daily News, 25 January 2016. <http://www.dailynews.lk/?q=2016/01/25/business/lanka-track-regain-gsp-daly>

21 “Sri Lanka on Track to Get GSP+, More Compliance Needed: EU Officials,” Economynext, 22 January 2016. <http://www.economynext.com/Sri_Lanka_on_track_to_get_GSP+,_more_compliance_needed__EU_officials-3-4058-10.html>

22 “Sri Lanka Businesses Must Lobby for Improved Human Rights to See GSP+ Reinstated Says EU Ambassador,”

Tamil Guardian.

23 European Commission, “The EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP),” April 2014. <http://www.sice.oas.org/TPD/GSP/Sources/EU_GSP_04_2014_e.pdf>

24 European Commission. “Joint Staff Working Document: ‘The EU Special Incentive Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance (‘GSP+’) covering the period 2014 – 2015.” 28 January 2016: 20, 35-36. 131.

25 European Commission. “Joint Staff Working Document,” 131.

26 Democracy Reporting International, “Stakeholder Forum GSP+ Pakistan,” 22 April 2016. <http://democracyreporting.org/?p=1440>

27 “Sri Lanka Businesses Must Lobby for Improved Human Rights to See GSP+ Reinstated Says EU Ambassador,”

Tamil Guardian.

28 See Observation (CEACR), adopted 2015, published 105th ILC session (2016), Right to Organise and Collective

Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98) – Sri Lanka (Ratification: 1972).<http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NO

RMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312243>