I use the hashtag #GoHomeGota to mark this watershed moment in Sri Lanka’s postcolonial history. It is in honour of the people who have stormed the streets to demolish the Bastille of a dynastic and nepotistic political regime that has left Sri Lanka in an economic meltdown. People of every class and creed have united against a “common enemy”; the Rajapaksas. Various kinds of rhetoric seep through “the struggle” to fight the Rajapaksas, and they require close scrutiny and unpacking for a more inclusive, pluralistic and egalitarian struggle. When I use the term “the struggle”, I use it to refer to the #GoHomeGota struggle, yet, with the awareness that this is not one homogenous struggle that can be captured with the term: Each of us engaging in this struggle come from diverse places and subject positions.

Therefore, it is simplistic to view this struggle as a monolithic or homogenous struggle – we should not expect it to be so. Every dissenter is an asset to this struggle.

#GoHomeGota, struggle or no struggle?

A main concern people seem to have about the protest waves in Sri Lanka is how “protest-y” they are. Youth who join the #GoHomeGota protest movement use various forms of expressing dissent, and some social media users criticize them for their supposed lack of seriousness and depth. This has created a divide among the dissenters. Social media narratives against these “not-so-serious” protesters undermine their contribution to the #GoHomeGota struggle.

A problem with this dichotomy is that it serves to constrict people’s forms of expressing dissent. A social media post that is in wide circulation say, “aragalaya aathal ekak kara noganna” [do not make the struggle an aathal/farce—although “farce” barely captures the nuances of aathal]. The problem is that we cannot expect the same reaction or response from all these groups as their needs, aims, feelings, struggles, reasons and reactions are diverse. Although this crisis has united people from all walks of life, we cannot view this as a crisis that affects every citizen alike: It affects people differently depending on factors such as class, gender, religion, ethnicity and caste that are very much active as we speak.

This diversity of our expressions of dissent is a result of the diverse subject positions we occupy, our privilege, and the creativity of our expression. The attempt to uniformize this struggle, in a way, waters down its strength and effect.

The struggles in Mirihana and Tangalle (but not limited to those) have been the climax of the pent-up anger and frustration of the working classes, (perhaps) especially the underclass, underprivileged and multiply marginalized persons and communities. Awakened by their struggle to make needs met, protesters representing various backgrounds took to the streets as a show of support. Therefore, it is simplistic to view this struggle as a monolithic or homogenous struggle – we should not expect it to be so. Every dissenter is an asset to this struggle. There is no template or format for struggles. Struggles and revolutions are diverse and this diversity should be embraced.

The dangers of trying to uniformize #GoHomeGota

This diversity of our expressions of dissent is a result of the diverse subject positions we occupy, our privilege, and the creativity of our expression. The attempt to uniformize this struggle, in a way, waters down its strength and effect. Uniformity in struggles also runs the risk of quick elimination in the face of counter-resistance, retaliation, and crackdown on the part of the government – diversity and inclusion increase protest strength. What is the point in uniformizing struggles? Will such predetermined models enable us to dismantle oppressive social structures and hierarchies that are always in the making?

#GoHomeGota and the question of egalitarianism: sexism and casteism

Kudos to the pressure we have put on the government through the #GoHomeGota movement. Yet, it is important to take a moment for introspection and reflection. Certain placards reek of sexism. For instance, Gotage ammata enna kiyapiya [ask Gota’s mother to come], and Gotage …. Gnanakkage katey [Gota’s … are in Gnanakka’s mouth]. Calling for Gota’s mother is a form of threat insinuating physical and sexual assault on Gota’s mother, and the second is a graphic sexual metaphor connoting that Gota is under the sway of his astrologer, Gnanakka.

Another text/catchphrase that reads Adoh naattami adu kuley upan …. invokes sexism, casteism, classism and snobbery. Although incoherent and fragmented, a loose translation of it would be; Yo, porter! Low-caste born … These words of a protester at the Mirihana protest site soon permeated social media as a catchy insult targeting Gota. The question is how a revolution is possible when we draw on such slurs with their basis in the very social structures and hierarchies that have oppressed us for centuries. When we have fought the oppressive clutch of casteism for generations, why do we now revive casteism in a fight against another era of oppression? If we perpetuate these slurs unquestioningly, it will only further marginalize the peripheries and exclude the downtrodden groups from this struggle for a corruption-free egalitarian society.

Living in Jaffna these past two years has given me a new perspective on how people view protests here. In Jaffna, people have been protesting for decades, but their suffering has gone unnoticed – does this #GoHomeGota protest wave recognize their suffering enough?

Talking about egalitarianism, let us also ask whose struggle this is, and who has access to this struggle. “The struggle” as manifested on the streets of the metropolis and centres may not be accessible to those who struggle on the peripheries of the peripheries who are multiply marginalised; minorities who do not speak Sinhala; and perhaps people who are excluded due to the digital divide. Furthermore, the Sinhala Buddhist hegemonic discourse feeds this struggle predominantly and obliterates the Tamil narratives and rhetoric. Living in Jaffna these past two years has given me a new perspective on how people view protests here. In Jaffna, people have been protesting for decades, but their suffering has gone unnoticed – does this #GoHomeGota protest wave recognize their suffering enough?

A fetish for kings and despots

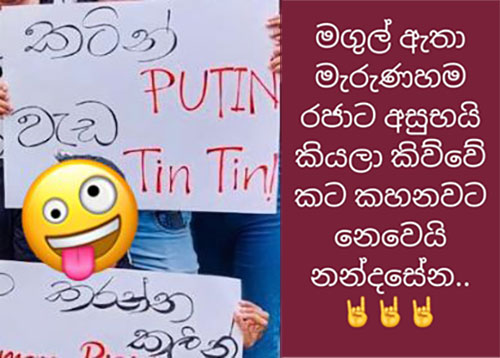

Although the #GoHomeGota movement is driven by the call for ending dynasticism, nepotism, totalitarianism and corruption, the unquestioning use of certain rhetoric imply the deep-seated and latent ideologies that subvert that cause by showing an underlying fetish for kings and despots. For instance, Katin Putin waeda Tin Tin, implying that Gota speaks like Putin but works like Tin Tin, is unacceptable on several levels: Tin Tin is a righteous, law-abiding honourable man whereas Putin is a megalomaniac who drove Russia to launch missiles and bombs on Ukrainians. The slogan implies a latent desire for a megalomaniac like Putin as opposed to the honourable Tin Tin. Is Putin the ruler we want? It is time for us to rethink the dangers of these catchphrases.

Another example, Magul aethaa maerunama rajaata asubai kiuwe kata kahanawata newei Nandasena, loosely translates to ‘it was not for no reason they said the death of the holy tusker brings bad luck for the king’. This is, of course, a reference to the passing of the tusker, Nedungamuwe Raja, but the inference is that there is a clear connection between the passing of Nedungamuwe Raja and the misfortune that befell Gota. This connection equates Gotabaya to a king and ties his fortune to the holy tusker who has a symbolic significance to the Buddhists – this rhetoric reinforces Sinhala Buddhist hegemony which in turn excludes those who are non-Sinhala Buddhist.

These -isms that are manifested in these protests also reflect the divisions and fissures in broader society including within supposedly progressive social movements. If we can address sexism, classism, casteism, racism and other failings, there is room for greater pluralism, egalitarianism and justice in Sri Lanka.

The creativity of placards, slogans and hashtags has taken the #GoHomeGota struggle to a whole new level. They are one of the driving forces behind this struggle and their contribution to #GoHomeGota shall not be undermined. Yet, let us not forget to reflect on the problems that spring up here and there. It is understandable that not everyone is capable of understanding the subtle implications or nuances of these texts and speeches that go viral on social media. It is the pent-up anger and the frustrations of the citizens that come out through these texts and speeches – (and perhaps these too have a purpose to serve?). To be both involved in this struggle yet distant enough to be self-critical is a great privilege not many can afford. It is one privilege education bestows on us. With that privilege, we cannot un-see certain ironies created through the kinds of rhetoric used in #GoHomeGota.

I like to quote my colleague, Anushka Kahandagama (also from the Kuppi Collective), who writes, “let me first of all pay tribute to free education and the people whose taxes funded free education for elevating me to a position of privilege where I can pause for a moment and analyze this situation”. On that very note, I write that it is important that we understand the underlying causes for these diverse narratives and rhetoric as we march forth. These -isms that are manifested in these protests also reflect the divisions and fissures in broader society including within supposedly progressive social movements. If we can address sexism, classism, casteism, racism and other failings, there is room for greater pluralism, egalitarianism and justice in Sri Lanka.

Erandika de Silva is attached to the Department of Linguistics and English at the University of Jaffna.

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.