By Nanda Pethiyagoda.

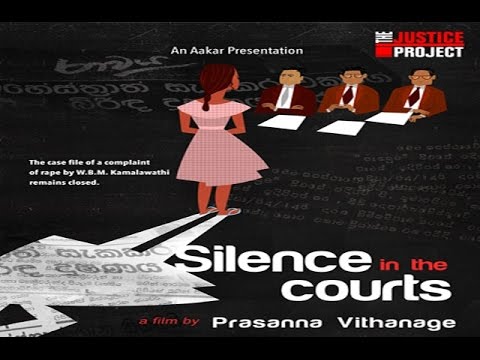

Thanks to the Colombo District Court that was not silent but judged fairly that the injunction brought against screening Usaviya Nihandayi produced by H D Premasiri and Prasanna Vithanage and directed by Vithanage, be set aside. The film is now screened for public viewing. It was scheduled to be screened at the Regal Cinema and other halls from October 4 but had to be held back till the enjoining order brought forward by the chief protagonist of the film, the magistrate, was over-ruled by the judiciary. .

I saw the film at its premier at the Regal Cinema on 19 September. I returned home with my head in a fair whirl and my sensibility determined to unravel the questions and opinions and write a comment on the one hour Sinhala film with English subtitling.

First thought and comment: it was a complete success in a new genré of Sinhala film. It was stunning; revealing with no hiding of names or important personages intertwining incidents of rape of two innocent and helpless women by a power that holds their husbands’ fate in its detestable, verminous, sexually greedy hand. The hand of a magistrate supposed to deal justice!

Advertised as a documentary, the film was completely different to the run of the mill films, whatever their language. Hence the adducible corollary that the director and producer have no eye on the box office nor on sammanas. I feel the motive behind the film was serving humanity and pleading for social justice, forcefully catalysed and prodded on by Victor Ivan who appears in much of the film as himself, the investigative journalist with a feeling for humanity strong in him, and human rights activist Dayapala Thiranagama. They comment on the reports they filed, Ivan in the Ravaya.

The first woman raped of the two featured in the film approach the two of them with her complaint, having gone to the Human Rights Commission, petitioned the BASL and even the President, with no results. This was around 1998. After much trauma and actual damage, Victor Ivan’s Ravaya exposé gets results, not real deserved justice and punishment and compensation to the gravely harmed family but at least knocking off temporarily a magistrate from his chair in courts.

Narratives

The film deals with two similar stories in the the 1990s where two working class men are judged to serve time in jail for petty crimes. Their young wives are summoned by the magistrate hearing the cases, aided and abetted by an Attorney-at-Law, on the pretext of recording evidence and being given some papers. The women naturally go as requested to meet the magistrate. They are raped by him, one far from her home in the Gampola Resthouse, the other in the Magistrate’s chambers. The exploitation of the first young woman is shown on screen in detail: without a word of by-your-leave after imbibing alcohol, the magistrate rapes her four times. Then he tucks in grossly to rice and curry.

When the first woman visits her husband the day his case is called after a lapse of time, he complains of her tardiness in visiting him and comments on her entirely different facial expression. Like all unsophisticated and faithful women, she confesses she was raped. Her husband’s response – a terrible slap through the cell bars to fell her to the ground and the threat of deserting her. But they make up later. The second woman’s husband goes berserk and plots and plans revenge as he says he cannot stand the insult to his manhood. He takes two bags of feces to courts and throws it at the magistrate, dowsing the rapist thoroughly with what he deserved. A bottle of some gas is also taken and when he dashes it against a wall, exploding it, everyone flees fearing a bomb blast.

Themes

Large and clear is the human condition – not only of the disadvantaged but the power wielding judicial persons, and brother lawyers who closed their eyes and ears to the fact that the magistrate had been sacked from a corporation for cheating and subsequently entered the judiciary. The fraternity took no notice of Ivan’s stunning headlines and reports in the Ravaya, until it became so substantiated with stark facts, that it could no longer be ignored; his calling for a presidential commission of inquiry to be instituted.

In much larger letters, in my imagination, right across the screen was written HUMAN NATURE. Yes, particularly the character make-up of the peasants of Sri Lanka who are depicted commenting in the film; the suffering wives; the high-ups and more so those who wield power over life and death, OK, imprisonment or freedom of a disadvantaged person and the vulnerability of young women with children, left to fend for themselves. Victor Ivan expresses the thinking of the few persons who have social consciences, who care for the welfare of their fellow human beings when he says he got interested in the case and took it on as an exposé since here was an innocent woman caught in a trap and having no recourse to any justice. As is the case in this country of ours, he found himself soon enough the target of threats, but he persisted, even traveling far out of Colombo when he heard the magistrate had raped another woman and was transferred to a remoter station down South. By now a judicial commission had been set up and the magistrate was found guilty. His punishment – compulsory leave with half pay! I wondered how he feels now. I do hope he is suffering. No pity felt as it was for the Supreme Court judge who was pitted against a domestic who he supposedly raped and tortured too. He fell off his balcony and that was the end of a silent, most evil man

Extra features to be commended

Silence in the Courts included many scenes with Victor Ivan and a few with Thiranagama, the former’s appearance prefaced or followed by the thundering roll of newspaper printing machines. The commission sittings and other interviews were sketched out and presented as drawings in shades of sepia. Much footage was of the first girl walking with a small child in arms and a boy of around six years beside her. She, the other woman and the men gave evidence or answered questions with facial silhouettes presented to the camera. Their faces seen sideways was what filled the screen. There were also scenes of deserted roads in thorn forests and the last scene which was a repetition of an earlier scene of a calm wewa surrounded by vegetation as seen from a passing vehicle. The film starts with the shot of railway lines and pans to the interior of a moving train. Actual scenes, plus symbolic, to be interpreted as one wished.

The next thought predominant in the mind, reinforced by the recent court judgement, is that justice is more alive than it was during the previous regime. The yahapalana government does not apparently allow (and definitely should not) extra judicial power to those high-ups in the legislature or judiciary.

Prasanna Vithanage is a film director of great expertise, and bold. He represents the social conscience that should be present in all of us collectively, but is sadly badly missing. He has to his credit films of merit deserving great credit but earning censorship, such as Oba athuwa, Oba Nethuwa which dealt with the doomed love between an ex-soldier and a Tamil girl sent to Bogawantalawa to escape being raped by soldiers in the North and/or conscripted by the LTTE.

Maybe being censored is a backhand compliment to his artistic excellence and right thinking. We congratulate him on this new film of his – not entertainment by any means but a cry, now fortunately not in the wilderness, but heard and echoed by many. We are, thankfully, living in better times, but of course exploitation of the disadvantaged still continues and rape is on the increase.

– courtesy The Island