- Police action that sometimes went beyond the call of duty sees positive results, says DIG Children and Women Abuse Investigation Range Renuka Jayasundara

By Dilushi Wijeinghe/Sunday Times.

DIG Renuka Jayasundara

When summoned for questioning, however, she denied any wrongdoing by her husband, her fear and loyalty towards him overshadowing her own well-being. But the police, who knew the facts of the case based on their investigations, took her case to court. And even there, she claimed nothing was amiss.

Determined to uncover the truth, the police directed her to a doctor for a medical examination. The results were harrowing—40 bruises, injuries and fractures told a story of prolonged suffering. Armed with this evidence, the court issued a protection order for her.

Despite the court’s intervention for what it felt was in her best interests, Kumari hired multiple lawyers to try and get her case withdrawn. But the system stood firm. She was given another court date and an order for family counseling.

“This case stands as a testament to the dedication of the Women and Child Protection Bureau [of the police], who went above and beyond to support a victim of domestic violence, even when she was reluctant to cooperate,” said Deputy Inspector General of Police (DIG), Children and Women Abuse Investigation Range Renuka Jayasundara.

Police in action

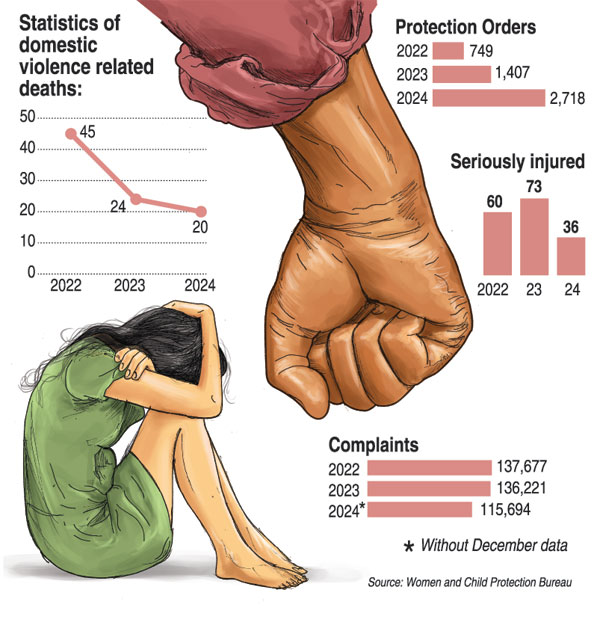

Since 2022, reported DV deaths have declined from 45 to 24 in 2023, then to 20 in 2024, with one recorded so far in 2025. DIG Jayasundara claims that the reason was “the implementation of the law.”

Jerusha Crossette-Thambiah

Domestic violence, meanwhile, is often underreported. Even those cases that do surface often come as a last resort. Tragically, there have been instances where victims have died without ever having had the chance to lodge a complaint. “When we conduct inquiries, it’s revealed that the deceased was a victim of DV but had never been able to complain,” DIG Jayasundara said. She also noted that statistics based on complaints were an unreliable indicator of how widespread the problem is, as victims often hesitate to report.

Despite the decline in deaths reported by the police, DV continues to be a significant concern. The United Nations Family Planning Association’s (UNFPA) 2019 “Women’s Wellbeing Survey” revealed that one in five ever-partnered (having had intimate relations, married or in a romantic relationship) Sri Lankan women have suffered physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner, with two in five women having endured various forms of violence and controlling behaviours.

Many survivors remain silent due to fear, stigma, or a lack of resources. Economic dependency on the abuser, lack of government support, insufficient subsidiary systems, as well as cultural and societal barriers prevent them from coming forward, leaving many cases unaddressed, as highlighted by DIG Jayasundara. She emphasised the need for comprehensive support systems to protect and empower survivors.

The prevention Act

The Prevention of Domestic Violence Act of 2005 aims to prevent DV and protect survivors. The Act defines DV as assault, threats, and emotional abuse. This violence can be physical or emotional and can be committed by different family members—not just spouses.

A key feature of the Act is the provision for Protection Orders valid up to a year. Upon the request of survivors, the court will issue an Order until a full hearing is conducted.

Additionally, the court may require the abuser to attend counselling sessions or provide financial assistance to the victim.

If the abuser fails to comply with the Protection Order, the accused will be charged with a 10,000-rupee fine or a year-long jail term.

Furthermore, the Act allows for Protection Orders even without proof of the abuser’s guilt, and preserves the survivor’s right to pursue other legal actions.

Both the survivor and the abuser have the right to request the court to alter, modify, extend, or revoke the Protection Order if there is a change in circumstances.

Shortcomings in implementation

However, social beliefs block effective implementation of the Act. One major reason for the failure of the DV Act is societal values prioritising family unity, DIG Jayasundara said. She said that people often see the Act as a threat to family stability, hindering its effectiveness, mirroring the challenges faced during its initial implementation.

Another significant issue is survivors’ lack of awareness about the Act’s existence. Many, even after filing complaints, are unaware that there is legal protection available. The DIG pointed out instances where survivors accepted whatever verdict was given to them due to their lack of awareness, including the option of obtaining a Protection Order.

Additionally, she pointed out that the police force’s knowledge on DV is insufficient too, despite its inclusion in their training syllabus, emphasising the need for societal attitudinal changes alongside legal enforcement.

Addressing DV in legal frameworks

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the surge in domestic violence cases saw the courts adapting to prioritise emergency hearings, even during lockdowns, said Attorney-at-Law, gender practitioner and lecturer Jerusha Crossette-Thambiah.

However, post-pandemic, the issuance of orders has seen a conservative shift. The legal expert highlighted cultural attitudes as a significant barrier.

Stakeholders perceive domestic issues as marital rather than criminal, despite the clear criminal nature of assault within a marriage. “A Protection Order doesn’t cause any prejudice. All it’s asking is that you don’t harass a person, so it should be given more readily. Why should somebody have a right to harass somebody?” she questions, adding that a victim should not be re-victimised in order to get a Protection Order.

Yet, the reality remains frustratingly different. “It’s very sad that in a country where 53% are women, you have to come and beg for yourself not to be harassed,” she says.

Counselling services also face challenges as many counsellors are under trained, often swayed by personal beliefs, failing to offer necessary support. “I’ve had counsellors who’ve sent back women to their abusive spouses because they think it’s bad for their religion,” Ms. Thambiah said.

Shelters for survivors are another area of concern. According to the Ministry of Women and Child Affairs, there are only ten government-run shelters for DV survivors. With limited facilities, many women find themselves choosing between abuse and homelessness.

This is exacerbated by inadequate gender budgeting, which often sidelines the needs of women and children in favour of other pressing issues. The lack of financial resources for shelters means that many women opt to stay in abusive environments, sometimes with fatal outcomes.

Awareness and attitudinal change are critical. Traditional methods of raising awareness, such as pamphlets often fall short, Ms. Thambiah says, suggesting more engaging means like community plays or tele-dramas that resonate with such issues, to spread the message.

Additionally, changing societal attitudes towards domestic violence is crucial. “The community must stand up for survivors, providing support and not judgment,” she urged.

|

Restrictions imposed by an Interim or Protection Order The Prevention of Domestic Violence Act allows the court to issue various restrictions on the abuser (known as the respondent) through a Protection Order to ensure the safety of the person experiencing violence (referred to as the aggrieved person). Firstly, the respondent can be restrained from entering the aggrieved person’s home, even if it is shared. Additionally, the respondent may be prohibited from approaching the aggrieved person’s workplace, school, or any shelter where they are staying. The court can also prevent the respondent from stopping the aggrieved person from staying in the shared home. In some instances, the respondent might not be allowed to live there at all. Contact with any children involved can be limited or completely restricted. Furthermore, the respondent cannot hinder the aggrieved person’s use of shared resources, such as money, vehicles, or household items. The respondent is also banned from contacting the aggrieved person in any form, including calls, texts, emails, social media interactions, or in-person approaches. To protect the aggrieved person’s support network, the respondent cannot be violent towards anyone assisting them, including friends, family, social workers, or medical professionals. Harassment, which includes following, bothering, or doing anything that could make the aggrieved person feel unsafe, is prohibited. Lastly, the respondent cannot sell or dispose of the shared home in a manner that would leave the aggrieved person homeless. The court tailors these prohibitions in the Protection Order based on the specific needs of each case. A protection order can either be obtained via the police or directly through courts with the aid of a lawyer.

|

|

| HelplinesFor DV related complaints, call the 24-hour hotline 109 or visit your nearest women and child protection bureau branch at any police division. You can also lodge complaints via email at [email protected] or send proof through the helpline’s WhatsApp on 071 859 5823. |