To that end, the Sri Lankan government has deployed a three-pronged strategy: ensuring that government departments and other state-controlled entities do not cooperate with the inquiry; criminalizing and obstructing the flow of information between witnesses and the investigation team through a renewed crackdown on civil society; and undercutting support for the international inquiry by beefing up – if only in appearance – its own (discredited) domestic accountability mechanisms.

The Presidential Commission on Disappearances (and other Failed Domestic Mechanisms)

In August this year the third element of this strategy received a boost when President Rajapaksa announced that he had appointed a panel of international legal experts to advise his Commission on Disappearances, whose mandate (it was declared at the same time) was to be radically expanded to investigate abuses committed during the final stages of Sri Lanka’s civil war, including violations of international humanitarian law and international human rights law. Given the strong evidence presented by the UN in support of allegations that between 40,000-70,000 civilians were killed during the final stages of the war, mostly by government shelling, it was a mandate that was pointedly phrased:

“[To investigate] Whether such loss of civilian life is capable of constituting collateral damage of the kind that occurs in the prosecution of proportionate attacks against targeted military objectives in armed conflicts and is expressly recognized under the laws of armed conflict and international humanitarian law.”

Originally established in August 2013, the Commission is the latest in a string of domestic accountability mechanisms with a severe credibility deficit. As the 2009 Amnesty International report “20 years of make believe”highlights, no less than nine presidential commissions have been established between 1993 and 2009, none of which resulted in significant change and many of which did not even produce published reports. The Centre for Policy Alternatives has listed eleven further bodies that have been established since then.

During its first year, the low expectations surrounding the launch of the latest Disappearances Commission have largely been confirmed. Not only has it been mired in allegations of witness intimidation, evidence tampering,outrageous mistranslations of testimony and procedural partiality – overseen as it is by a government with a track record for eliminating witnesses to war crimes – but it has proceeded so slowly that it has been estimatedthat it would take the Commission 13 years to hear all the complaints that have been lodged before it. [1]

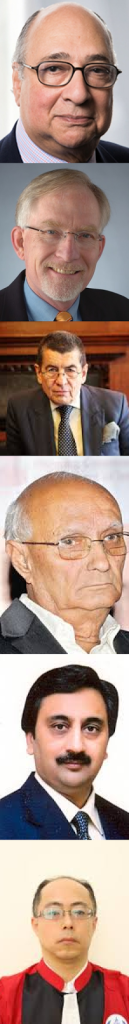

In this context, the appointment of three international legal experts, David Crane, Geoffrey Nice, and Desmond de Silva, to oversee this process, was greeted by many human rights observers with surprise.

Why had a group of seemingly distinguished lawyers, with a wealth of experience in prosecuting war criminals across the world, chosen to act as a convenient political cover for a government itself accused of the gravest war crimes? And why had they agreed to associate themselves with a process so obviously flawed, and so clearly designed and timed to undermine a credible and independent international inquiry? On what specific basis had they been hired by the Sri Lankan government, and how, given the seeming conflict of interest between providing legal counsel to the Sri Lankan government and advising a domestic accountability mechanism, was their role to be defined?

Advisors on Accountability or Counsellors to the Accused?

Several of these questions were recently posed by the Sri Lanka Campaign to the group of advisors – now recently expanded to include the Indian development activist Professor Avdhash Kaushal, the Pakistani lawyer Ahmer B Soofi, and former international judge Motoo Noguchi.

Only two of the experts replied, and while the Sri Lanka Campaign agreed to keep the correspondence private, we can reveal that Professor Kaushal’s response was brief and evasive, and Professor De Silva’s response was in line with his public utterances – that he sees his role as analogous to that of a barrister representing a client. This was a view echoed by Sir Geoffrey Nice, who, in response to our questions at a public event in October, invoked his professional obligation under the ‘cab rank rule’ to offer legal counsel to clients irrespective of his personal views about them. This is a defence that does not stand up to scrutiny.

To begin with, the Code of Conduct of the UK Bar Standards Board (of which Sir Geoffrey was formerly vice-Chair) clearly states that foreign work – i.e. services relating to legal proceedings taking place outside of England and Wales – is not subject to the cab rank rule. The suggestion that the advisors are therefore compelled by professional duty to provide legal services to the Rajapaksa government is therefore spurious.

Second, by invoking the cab rank rule the legal advisors give the impression that there is some sort of credible prosecution mechanism underway against the Rajapasksa which would cause them to require legal advice. There is not, and indeed this appointment seems to be an attempt by the Sri Lankan government to influence the politics of the case to ensure that there never is.

Lastly and most importantly, by outlining their engagement in terms of a lawyer-client relationship with the Sri Lankan government, the advisers reveal the fundamentally flawed nature of their dual appointment. For while they have been eager to present themselves as legal counsellors to the Sri Lankan regime, their stated official role, as specified the revised mandate of the Commission, is: “to advise the Chairman and Members of the [domestic] Commission of Inquiry, at their request, on matters pertaining to the work of the Commission”.

It is our view that there is a fundamental incompatibility between these two tasks – and moreover, that there is a direct conflict of interest between advising a Commission designed to investigate serious violations of law and the task of providing legal advice and representation to the individuals and agencies who stand accused of them.

Outstanding Questions

In certain circumstances, international lawyers can play an important and valuable role in the design of domestic transitional justice mechanisms – providing as they often do, the impartial and non-political expert legal advice that their credibility requires. However, it is clear that in the case of Sri Lanka, where the repeated failure of such mechanisms to achieve justice prompted the creation of an international accountability process in March of this year – and where such mechanisms continue to be used to undercut support for that very process – no such useful role is possible.

This international mechanism must be allowed to do its work and the eminent international lawyers should take great care to avoid being complicit in undermining it. While they may claim that they are bound by ‘client confidentiality’, the controversial dual nature of their role, the possibility that their work is being used by perpetrators to evade international justice, and the very serious allegations that the proceedings of the Commission are now being used as a vehicle for witness intimidation by Sri Lankan security forces, all place a strong moral and professional obligation on the advisers to clarify their precise mandate – the lack of clarity over which has been noted by both the Sri Lankan think-tank the Centre for Policy Alternatives (p. 7-8) as well the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in his recent oral update (para 34).

In failing to do so, they will continue to fuel the suspicion that they have been hired by the Sri Lankan government to support its goal of undermining the international investigation. And while it may seem absurd to suggest that the addition of individuals who regards the Government of Sri Lanka as their client to an accountability process can in any way give added credibility to that process itself, that appears to be precisely what the Sri Lankan government is hoping to achieve.

Footnote

[1] For a comprehensive and up to date critique of the work of the Presidential Commission on Disappearances, see: ‘The Presidential Commission to Investigate into Complaints Regarding Missing Persons: Trends, Practices and Implications’, Centre for Policy Alternatives (17 December 2014)

Richard Gowing is the Deputy Campaigns Director of the Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice. He holds an MSc in International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies from the London School of Economics where he graduated with Distinction. He currently also works at the Chatham House US Project.