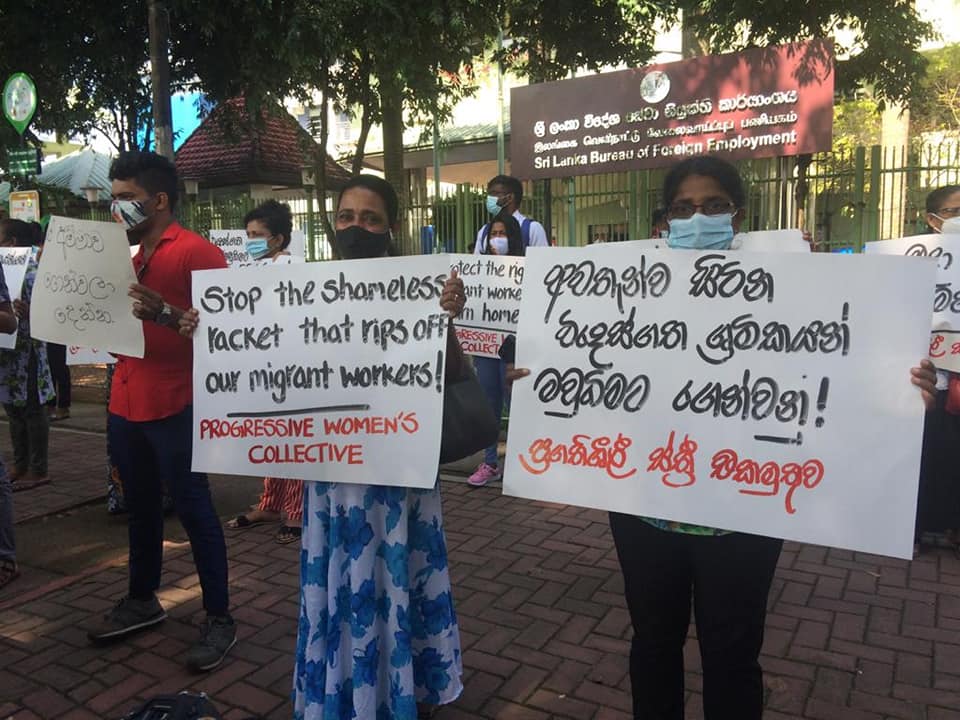

Image: Activists protest in Sri Lanka against the discriminatory treatment of migrant workers. ( FB photo, January 2021)

The year 2020 was a horrible year across the world with the rapid spread of the covid19 virus that turned out to be a global pandemic. The virus spared no one. From presidents and celebrities to common citizens, from rich or poor countries, they were not spared.

Migrant workers suffered much greater consequences than most other citizens as many were left in the lurch to fend for themselves as both origin countries and destination countries let them down and let them down badly.

The rapid spread of the virus has not slowed down. In fact, it has given rise to other fast spreading variants and strains that are extremely mobile and virulent across nations, borders, and continents. The global vaccine drive will slow down infections but is not likely to see a control of the spread anytime soon. It is likely to take over year or two years or longer for universal coverage of the vaccine to take full effect.

The following narrative looks at the many shortcomings of destination countries and origin countries in meeting the fundamental needs of migrant workers social security and social protection.

In destination countries

- A migrant worker’s status and recognition in a destination country is not the same when compared to that of a national in a destination country. Some destination countries even deny recognition, protection, and benefits of low skilled women workers like domestic workers who are not considered part of the labour laws of the country. There are short term seasonal workers who are also denied their social benefits on the grounds that their contracts are too short to be considered any payments or benefits.

- Migrant workers are often denied social security benefits in destination countries because they are not nationals of the destination country. The social benefits that are denied are health benefits that include occupational health and safety protection. Many are the instances where migrant workers are repatriated on grounds of health. Many have been repatriated owing to occupational injuries without insurance payments. Many are instances where compensation has been overlooked or adequate payments denied to the next of kin in occupation injuries and death.

- They are denied their agreed wages as there are unreasonable deductions enforced upon the worker. Their overtime payments are denied. Their promotions and increments are denied. Not all employers have a gratuity scheme. Those who have a scheme don’t guarantee full end of term gratuity benefits. Gratuity payments don’t exist in the informal sector such as domestic work.

- Their contract grievances are overlooked. Even though labour reforms are being discussed and promises of the Kafala system is being reformed migrant workers are denied their fundamental benefits such as their wages, more so in the low skilled labour categories.

- Migrant workers who have attempted to complain to the local labour authorities are often denied their case as they don’t have legal support and language is a huge deterrent to pursue the case. It is hardly of any use in obtaining consulate assistance as such assistance is not freely available.

- Given some of the above anomalies and irregularities that migrant workers face in destination countries, they are forced to be undocumented migrant workers that make their cases that much more difficult to pursue with the authorities.

- Ultimately, migrant workers who are labelled as undocumented workers and whose cases are pending are offered an amnesty to leave the country or face imprisonment and penalties and be barred from entering the country again. We must realise the undocumented status is not earned by the migrant worker. It is a label imposed on them for the many shortcomings of the labour systems and practices and contract violations in destination countries.

- Migrant workers who use the legal banking system to remit money back home are charged bank charges and other “related” transaction charges. This also implies that every time a worker access the bank to make a remittance s/he is charged a transaction fee.

In origin countries

- Origin country authorities fail to address the social security benefits with their destination country counterparts, employers, and recruiters for fear of losing job orders to other nations.

- The investments made by origin country consulate offices on behalf of addressing migrant worker workplace grievances is very marginal. Because it is an expense, such facilities are often denied unless they are amicably resolved. Consulate staff lack the wherewithal and commitment to take up cases for many reasons such as staffing, follow up, reporting, budgets etc.

- Local banks charge migrant workers a hidden transaction cost on withdrawals and payments by way of tax. There is no real benefit to the migrant worker who is a primary contributor for foreign exchange to the national coffers.

- The covid19 uncovered many irregularities on the part of the authorities in the repatriation of migrant workers. Firstly, governments failed to recognise the undocumented migrant worker. Government of Sri Lanka failed to repatriate workers free of cost. The repatriation, covid test and the quarantine facility was packaged similar to tour packages charged by a travel agent. The repatriation process became a business. Many migrant workers were forced into further debt.

- Governments including the Sri Lanka government failed to address migrant workers sudden retrenchment from service and the loss of wages and social benefits. Migrant workers were thrown out of their housing facilities and were deprived of food. Many were living in street and in parks.

- A fundamental right of paying compensation from national funds to those who perished owing to covid19 related complications were denied any form of compensation because they were undocumented workers.

- In Sri Lanka, the authorities failed to make any form of compensation and or livelihood payments to migrant workers who returned emptyhanded, distressed, and depressed either through the insurance scheme or the migrant workers national welfare fund.

- Sri Lanka government further denied and deprived migrant worker access to in service legal and consular services and social security protection as the government decided to downsize consular cadre in over a dozen labour receiving countries siting “lack of funds.”

Reflections and recommendations

- As the covid19 has dismantled, derailed, and disrupted established structures, institutions and frameworks between nations at the bilateral and multilateral level, we all have an urgent responsibility to come together and rebuild these institutions to where we were or go many steps beyond to where we want to be in the global migration discourse.

- We must, in fact, treat this stage of our journey as new beginnings. Build on stronger diplomatic relations, build on inclusive labour laws and social security for the migrant worker community, and recognise and respect the community for the services they render in the destination countries and origin countries.

- Health practices have changed since the covid19. With it, a host of social behaviours and practices have come to stay along with new country regulations and labour regulations. We must shun the stigma and discrimination that migrant workers receive in these circumstances and introduce inclusive community practices which is the only way to fight a pandemic of this proportion.

- Migrants often have to pay for many things including their air passage. They have to pay fees to recruiters. They have to pay for insurance cover and a registration fee at the origin country. They have to pay for a pre departure medical test. The benefits that accrue from these payments have not helped the migrant worker. In fact, they have deprived the worker. The moment has come to change these practices and bring about true commitment in policy delivery.

- The time has come to revisit and reframe the BLAs and the MoUs inspired by the many international conventions available to us. The time has come to reframe the contracts between employee and employer with fundamental social benefits and protection. The time has come to take in the consequences of health crises like the covid19 and ensure migrant workers are not victimized in retrenchment, wage theft and social justice.

- Governments have been talking about retirement benefits and pension schemes for migrant workers for many years. These discussions surface closer to national elections to win a vote. Whilst it is acknowledged that some governments have implemented such schemes, it is the right time for those governments who have been dillydallying to step up and fulfil their promises to the migrant worker community.

It has been proven time and again that no government can pursue this journey alone. Governments that are taking hardline, exclusive, and unilateral approaches to migration are not doing justice to their migrant worker community. Governments must recognise the multi stakeholder influence in their countries, listen to their voices and most importantly listen to the voices of the migrant community in making policy and in addressing migration issues to build a better future for all.

Andrew Samuel, Community Development Services (CDS), Colombo, Sri Lanka.