Dr. Udari Abeyasinghe and Dr. Kalana Senaratne.

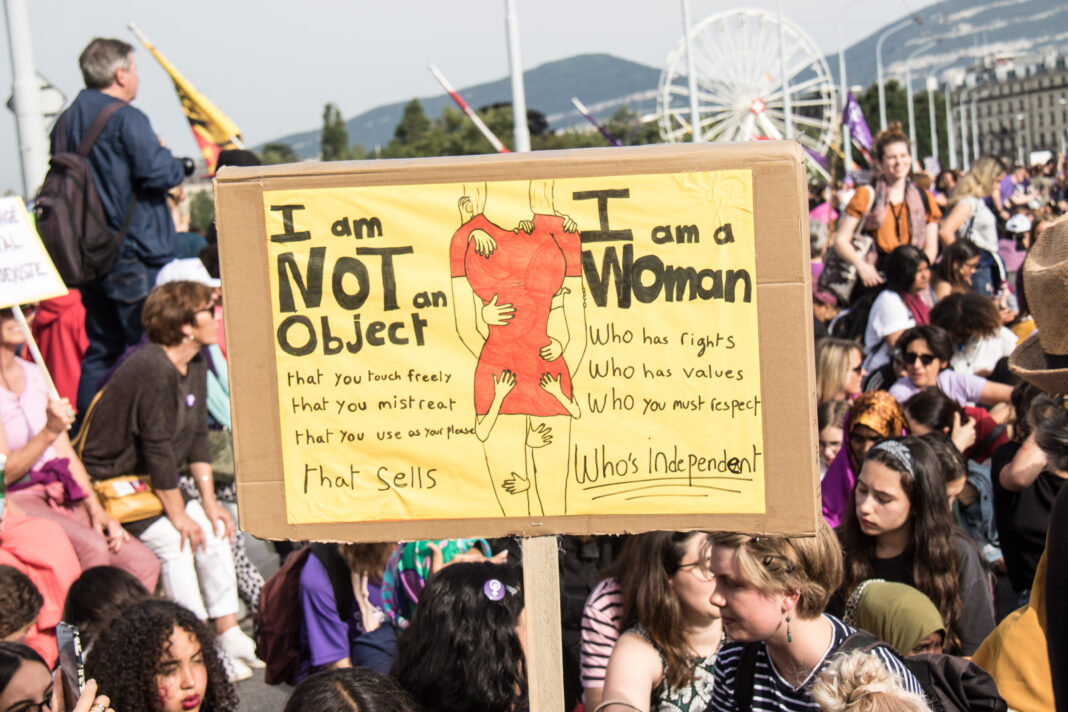

The law criminalizing sexual harassment could change very soon. A bill, which proposes to amend S. 345 of the Penal Code, has been gazetted. This is a welcome development. Yet amendments to the Penal Code are insufficient to tackle sexual harassment which women, in particular, have to undergo on a daily basis.

Sexual harassment is a relatively new offence. Initially the Sri Lankan Penal Code, enacted in 1883, contained a provision – S. 345 – which referred to the offence of assault or criminal force directed at women with the intention to “outrage her modesty”, a provision similar to S. 354 of the Indian Penal Code that was not broad enough to cover the concept of sexual harassment as it is understood today.

In 1995, the local criminal law underwent some modernization. While new offences such as Grave Sexual Abuse (GSA) and the sexual exploitation of children were added to the Penal Code, S. 345 was amended in a way that criminalized three offences, namely:

- Sexual harassment by assault;

- Sexual harassment by criminal force; and

- The use of “words or actions” which causes “sexual annoyance or harassment”.

Sexual harassment was now a distinct crime carrying a punishment of a maximum term of five years imprisonment and/or a fine with the additional possibility of compensation being awarded to the person who suffers injuries. However, as Wing-Cheong Chan, et al point out in their study titled Criminal Law in Sri Lanka (LexisNexis, 2020), this provision can be unnecessarily confusing. Instead of a single offence of sexual harassment, there are three different offences involving three sets of different elements.

Reform was therefore necessary; greater clarity was required about the nature of the offence. Greater clarity was also required on whether S. 345 captured different forms of sexual harassment that take place today through modern technology and communication devices.

Amending S. 345 of the Penal Code

In December 2022, it was reported that the cabinet had approved a proposal to strengthen the Penal Code provisions on sexual harassment including the criminalization of sexual bribery (The Morning, December 14, 2022).

On 4 July 2024, a bill to amend the Penal Code was published in the gazette. The proposed provision makes two significant additions to S. 345.

Firstly, in addition to the elements of sexual harassment in S. 345, the proposed amendment criminalizes sexual harassment “by means of any communication.” The word “communication” includes “transmitting, distributing, sharing, generating, propagating or publishing any sexually explicit message, remark, image, audio or video through electronic means or internet.” There is an explicit recognition of how modern technology contributes to sexual harassment.

Secondly, the proposed amendment clarifies what is meant by “use of words or actions” which could cause sexual annoyance or harassment. This includes, for example, the making of any sound or gesture; exhibiting any object; disrobing or compelling a person to be naked; physical contact and advances involving unwelcome and explicit sexual overtures; demands or requests for sexual favors; showing pornography against the will of a person; making sexually colored remarks; or exposing genitals with the intention of causing alarm or distress. This is a non-exhaustive list.

The proposed amendment expands the scope of the existing law and clarifies what acts can be considered as amounting to sexual harassment. However, when compared with the law in comparative jurisdictions, the new amendment does not adequately capture such offences as voyeurism and stalking.

Revisions to the law are undoubtedly necessary. An improved legal framework facilitates the realization of greater justice to the victims. Therefore, the provisions that exist currently relating to sexual harassment in the Penal Code and in other laws (such as the Bribery Act, the Industrial Disputes Act and the Prohibition of Ragging Act) can play a very helpful role. Yet, the law is an inadequate means through which sexual harassment can be curbed. In fact, the law is hardly resorted to by victims who suffer sexual harassment on a daily basis. As Dr. Arosha Adikaram discusses in Dealing with Sexual Harassment in the Workplace(Stamford Lake, 2017), this is due to a number of reasons, such as the costs involved, the time consuming nature of legal action and the lack of trust in the legal system.

Our experience also suggests, as highlighted by many experts, that there is more to be done especially at an institutional level. This is the case at universities. This needs to be highlighted for it is easy to lull ourselves into imagining that the law’s improvement would necessarily lead to a decrease in the occurrences of sexual harassment. Far from it.

Three aspects we wish to briefly highlight are the following:

Attitudinal shift

Firstly, the importance of an attitudinal shift about how we understand sexual harassment, its seriousness and more broadly about gender-based violence cannot be stressed enough. As Dr Janithri Liyanage and Prof. Kamala Liyanage in a chapter entitled “Gender-Based Harassment and Violence in Higher Educational Institutions: A Case from Sri Lanka” have argued, “questioning the very foundation of our understanding of ourselves and our social relations” is essential if we are to address the problem of sexual harassment and gender-based violence in a meaningful manner (Ishtiaq Jamil, et al, Gender Mainstreaming in Politics, Administration and Development in South Asia, Springer, 2020).

Fundamentally, the progress we make in terms of reducing the occurrences of sexual harassment or in terms of investigating and taking action against perpetrators of sexual harassment depends on what our attitude is towards the nature and gravity of sexual harassment. It depends, in turn, on how sensitive we are towards the promotion of gender equality and equity because sexual harassment, targeted predominantly against women, is a reflection of the continuing inequality women have had to face in society and in specific institutional settings. This attitudinal shift should happen within the seminar rooms of universities where senior academics and administrators meet.

Radical awareness

Secondly, there is the need for “radical action” especially in terms of building greater awareness about sexual harassment and its pervasiveness. How is this to be done?

Most universities have adopted policies on the prevention of sexual harassment. The University of Peradeniya, for example, has a Policy on Sexual or Gender-Based Harassment and Sexual Violence and has a separate by-law which provides for, inter alia, preliminary investigations, mediation and formal inquiries. Since its adoption in 2018/19, the University of Peradeniya has prioritized raising awareness about sexual and gender-based violence prevention by incorporating discussions, about the policy, into student orientation programs as well as staff training programs.

However, we believe that such awareness should form an essential part in the many leadership training programs that are now conducted aimed at Heads of Departments and senior academic staff. This is certainly not a matter which can be limited to staff induction or student orientation programs. But it is not only about raising awareness. A more concerted and practical effort needs to be made to discuss why speaking about and investigating allegations of sexual harassment is difficult: Why is it difficult? What or who makes it difficult? Who blocks action from being taken against perpetrators? Where do investigations get stuck if at all? How does the system prevent meaningful resolution of such cases? Are these problems associated with individuals, with the system or both? These are some of the issues which would need to be taken up openly during deliberations and discussions on this topic.

There is also the urgent need to ensure gender balance in key decision making bodies at universities from the topmost body (the council) to departmental level committees. Such gender balanced bodies would foster trust within the university community, particularly among women, by demonstrating that their concerns are taken seriously and addressed fairly. They also help to mitigate the influence of stereotypical and prejudiced thinking about gender roles and behavior. By striving for gender equity in decision making processes, universities would reflect their commitment to gender equity and fairness, not just in theory but in practice as well; all of which relate, in turn, to how we address issues of sexual harassment.

Judicial imagination

Thirdly, a critically active judiciary is always an important ally in this struggle against sexual harassment. Impactful and effective judicial decisions not only generate confidence but they boost the task of awareness building as well. The manner in which the Indian judiciary dealt with the issue in the 1990s, for example in the landmark case of Vishaka v State of Rajasthan and the subsequent developments in the Indian law, come to mind.

The Sri Lankan courts deserve credit for being progressive on this front especially in recent times. In LD Sanjeewani v RMSN Gunathilaka (decided in June 2024), the Court of Appeal overturned a decision given by the Trincomalee High Court and held the accused guilty of the three counts of sexual harassment he was alleged to have committed in 2011. In doing so the court corrected an utterly erroneous understanding exhibited by the Trincomalee High Court of the elements of the offence of sexual harassment that had to be proven.

The Supreme Court has also been very progressive in this regard. In Sri Lankan Airlines v PRSE Corea (decided in February 2024), Justice Janak De Silva, writing the determination for the Court, stated that sexual harassment is a criminal offence which amounts to very serious misconduct at the workplace. Particular note was taken of the physical and mental trauma that victims of sexual harassment undergo and considered sexual harassment to be a violation of fundamental rights, echoing the sentiments of the pioneers who were instrumental in criminalizing sexual harassment globally such as Catharine MacKinnon. Referring to Sri Lanka’s international obligations, it was stressed that equality in employment can be seriously impaired when women are subject to gender-specific violence such as sexual harassment.

These determinations go a long way in generating the broader shifts in attitude and approach required to address issues of gender-based violence and sexual harassment. And in a context where media reportage plays a significant role, it follows that there is a tremendous dampening of spirits when the judiciary delivers determinations which lack nuance and sensitivity. It was only a few days ago that the Kerala High Court held that a woman cannot be charged with sexual harassment of another woman. (Hindustan Times, August 17, 2024). Over time, the superior courts of India may correct such interpretations. But this goes to show the broader, even psychological, role judicial institutions and interpretations can play in society.

There is also the need to revisit and rethink some of the traditional concepts we encounter in law such as the “reasonable man’s test” and question how such concepts may need to be reformulated and reconsidered in ways that enable the sensitivities of women to be taken into account. In other words, even if we reform the law in books such as the Penal Code, the lens through which we see and interpret the words in those books matters a lot. Without a change of the lens we might never encounter the victim’s reality.

On the struggle for equality, Andrea Dworkin once stated: “We have to work an awful lot harder, an awful lot harder, because the equality we are looking for is going to be given, if at all, only after the most crucial, bitter, and often demeaning fight.” The battle to eradicate or even minimize sexual harassment is also an equally arduous task; one which involves the need to work an awful lot harder. Improving the law is only a part of the hard work required while much more remains to be done.

Dr. Udari Abeyasinghe and Dr. Kalana Senaratne/ Groundviews

Dr. Udari Abeyasinghe is a Lecturer at the Department of Oral Pathology, Faculty of Dental Sciences, University of Peradeniya. Dr. Kalana Senaratne is a Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of Law, Faculty of Arts, University of Peradeniya.